Famed Million Dollar Courthouse jail maybe not so secure

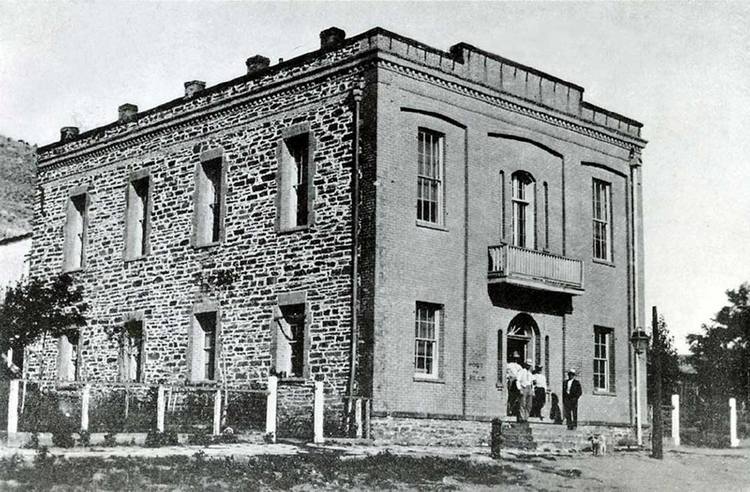

When you come to visit in Lincoln County sometime, plan to make a stop in Pioche at the Million Dollar Courthouse.

It’s not used anymore, not since 1938 anyhow, and is now a a tourist attraction and museum. The present Lincoln County Courthouse opened in 1938. Interestingly enough, the present courthouse has served longer than the old one did. Both are on the National Registry of Historic Places.

A million dollars for a courthouse is not an exorbitant price in today’s world, but back in 1872 it certainly would have been. By the time it was all paid off in 1938, the overall costs came to a little over $1 million. That would be have been equivalent to $16,340,000 in 2017.

But that is not the focus of this story, although it certainly could be. Instead, if walls could talk many a good story would be told from the jail in the old courthouse building. Author Leo Schafer has several stories in his book Law and Disorder in Pioche.

The mining boom in the town of Pioche was just after the Civil War and into in the early years of the 1870s. Pioche had plenty of law breakers who were sentenced to jail for various lengths.

Schafer writes, “The jail (located in the basement of the courthouse) was described as a dark dungeon where inmates could sit or recline on the floor, beds, or stools. The cells were for solitary, or almost solitary confinement.”

Inmates often played cards with each other to pass the time. Schafer notes, “one of the prisoners even lost a knife in a bet.”

Late in 1872 and nearly all of 1873 was an eventful period in the early life of the jail.

Schafer writes that in November, 1872, “Black Hawk” Oreamuno committed suicide in his cell. He had been arrested a few days prior for “displaying indications of a disordered mind,” having even gashed his own neck with a knife.

Locked in a cell one day, “the very next night,” Schafer wrote, Black Hawk tore a two-inch wide strip from his bed tick, tied one end to the grate on his cell door, made a double turn around his neck with the other end, stood on a bucket and stepped off. Efforts to revive him failed.

“Chicken-Thief Charley” Roddo was a frequent visitor to the jail during that same period. Schafer relates he was a kleptomaniac, “prone to take anything that wasn’t nailed down, including chickens, obviously.” Charley didn’t have to escape from the jail. He would be released shortly thereafter and be back again in no time.

Then there was Frank Perry. In January, 1873 he had been tried and convicted of a robbery which occurred earlier that fall. He had been in the jail for several months and was considered “harmless.” Perry even helped out around the courthouse, pushing broom, emptying trash, washing windows, cleaning offices, etc. One day, Schafer notes, Perry complained of not feeling very well, asking to go to vomit or some such thing. Sanitary conditions in the overcrowded jail were not good, and Perry was allowed to go outside. Seeing the road unguarded, Frank took off running. He made it almost to Panaca, 11 miles south, then headed east toward Utah territory, before officers caught him again. He was returned to the jail to finish out his sentence, plus what was added on for escaping. He did, probably in large part because he was not given a chance to escape again.

A most interesting escape attempt was discovered in the late spring of 1873. The jailer noticed inmates in one particular cell all seemed to sleep in one place, up against the east corner. Being suspicious, the jailer found that the inmates “had loosened all the stones at the south exterior wall. An escape could have been made in moments.”

The sheriff was notified and made arrangements for repairs, which included installing iron bars where the stones had been loosened. Schafer writes, “Until the repairs were completed, the jailer temporarily slept in that same corner providing extra security.” Schafer does say this, but it would be assumed the jailer slept on a cot on the other side of the bars.

Even more elaborate was the plan James Harrington hatched later that fall. Having been convicted of second degree murder in September, 1873, he was in the jail awaiting sentencing. He planned to escape, but the plan was foiled when another inmate tipped off officers. What they found was, in the back corner of his cell, Harrington had loosened the bricks, and created a hole approximately about 30-inches wide in the wall that was about two-and-a-half feet thick. The hole on the outside was only a couple of inches wide at this point. But Harrington had help from an accomplice on the outside, too, because the ankle chain Harrington wore when later captured, had been completely cut through by a tool smuggled in to him.

The outside escape route led to a dirt covered shed. Schafer writes that inside the shed were “a pinch bar, one-and-a-half feet in length; a file transformed into a cold chisel; and a case knife that had been converted into a saw.”

The accomplice was not identified, but Harrington was moved into a different cell and later received 15 years in the state penitentiary. No word on what happened to him there or after. He would have been released in 1888.

One always wonders, could the famous Harry Houdini have escaped from the Million Dollar Courthouse jail? Despite all the best safeguards of the day, he probably could have.

— Dave Maxwell