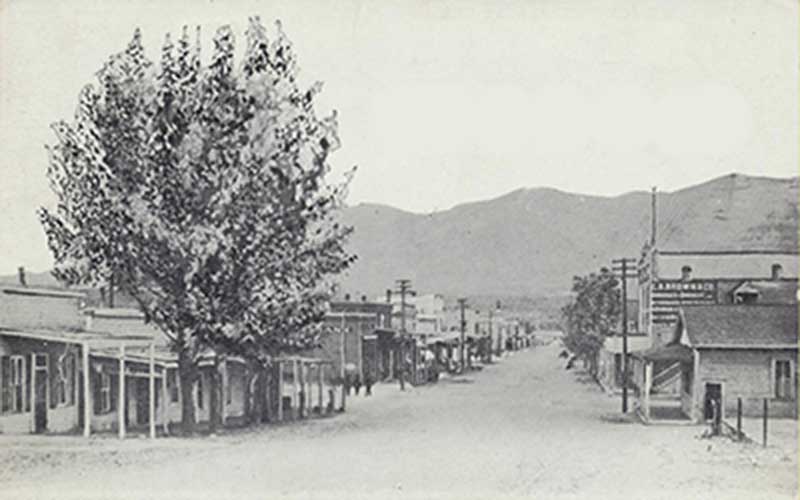

Winnemucca is a tranquil town on the Humboldt River, a trading post transformed by the railroad into a lively shipping center, a bumptious cow town and county seat. Its history resembles that of dozens of other Western railroad towns, except for one transcendent event.

On September 19 1900, the story goes, Butch Cassidy rode into Winnemucca and robbed the local bank.

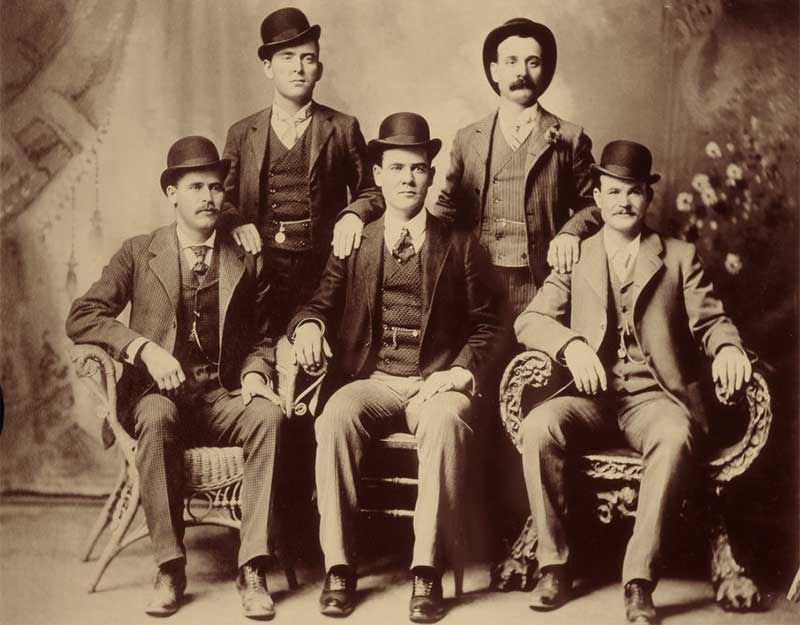

Butch and the boys got clean away, galloping out of town in a hail of bullets with $32,000 in gold. Later on, the story tells us, he added insult to injury by sending the bank a photograph of himself and the boys in fancy new suits, stiff collars and derby hats. With it was a mocking thank-you note expressing appreciation for the Winnemucca money they were spending on their fun.

It is a delicious story and has been told and retold countless times. I have told it myself. It is such a wonderful story that the community for many years celebrated Butch Cassidy days each September in honor of the great event.

But unfortunately it is not a true story. In fact Butch Cassidy didn’t send that picture and the evidence is clear that he was never in Winnemucca in his life.

The robbery did take place, of course. Maybe Butch Cassidy knew it was going to happen. He may well have had a hand in making the arrangements, and it is clear that some of his larcenous friends in the Wild Bunch were involved. But no matter who robbed the Winnemucca bank no-one who was there that day ever forgot it.

The Boys

Winnemucca 1900. Like a new mother gazing down at her sleeping babe the September sun lavished light and warmth on the dusty burg at the Big Bend of the Humboldt. The town was busy with stockmen buying and selling cattle and horses when sharply at noon the schoolhouse doors burst open and the pent-up kids came streaming out and down the steps to home for lunch.

Some of the boys liked to walk down Bridge Street to the river and chunk rocks into the water until it was time to go back to class. So it was that nine-year-old Lee Case and a couple of pals were on their way back from the river one day when they trooped past the empty livery stable and saw some cowboys sitting by the open doorway. In their friendly way the cowboys struck up a conversation with the boys. The next day they saw the men there again and talked with them some more. They were just drifting cowboys passing through, making small talk about the town, wondering how many deputies there were and one thing and another.

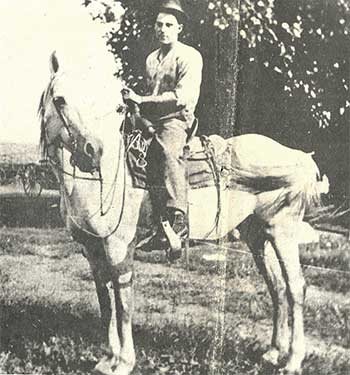

East of town about 10 miles another boy got to know the cowboys. Ten-year-old Vic Button rode into Golconda to school by horseback from the CS Ranch every day, passing their camp in a field down near the river where there was a well for drinking water. There was nothing out of the ordinary about that, the roundups were about over and plenty of Cowboys were moving through the country. Vic would’ve ridden right on by the men’s camp except for the handsome white horse that caught his eye.

Vic rode over and asked the cowboy if he’d like to trade his white horse. The cowboy laughed and said, “No, he’d keep him a while” but Vic had fallen in love with that big white horse. The next day at his father’s ranch he picked out a fine strong saddle horse and rode it to the camp on his way to school in hopes of a trade, but it was no dice. The cowboys were friendly and jawed with the kid, and wondered out loud of what the best way might be to get to southern Idaho in a hurry from there and then nodded their heads when Vic pointed out Soldier Pass.

Vic rode a different horse past that camp to school each day, hoping one of them would take the cowboy’s eye the way the white horse had taken his. But the cowboy wouldn’t trade.

The Holdup

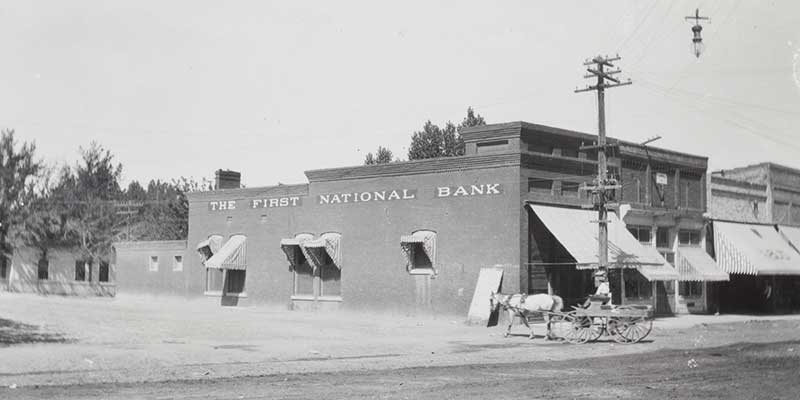

September 19th was another golden day, and at noon the schoolboys hurried home for lunch as usual. Carl Smith took his customary route to the corner of Fourth Street and then turned to walk along the sidewalk next to the First National Bank. As usual he looked in the window as he went by.

But most unusually he saw Mr. McBride, Mr. Calhoun and Mr. Hill standing by their desks behind the customer counter with their hands up in the air. Two men were pointing long-barreled pistols at their frightened faces. Over by the big safe, a man with a scraggy yellow beard had hold of Mr. Nixon by the shoulder with one hand and with the other held a great gleaming knife at his throat.

Carl walked directly home as usual, ate his lunch in silence and went back to school by the long way, so completely flummoxed by what he’d seen that he didn’t say a word about it to anyone until it was all over.

Meanwhile Lee Case and Slats Rutherford were walking past the Courthouse when they heard a burst of loud popping and stopped in wonder at the sound.

What they heard was George Nixon shooting his six-gun in the air on the street outside the bank. He had opened the safe with that knife at his throat and watched helplessly as the bearded man reached in and thrust three bags full of gold coins into an ore sack that he had brought along. Afterwards he emptied the money drawers in Nixon’s private office of the ten- and 20-dollar gold coins kept there.

Then everyone had been herded into the bank’s small back yard, Nixon and his three employees and W.S. Johnson a horse buyer who had been in Nixon’s office when the robbers arrived. While the bearded man held them at gunpoint the other two robbers jumped the back fence and ran down the alley to their tethered horses. When the man with the blond beard had gone over the fence after them Nixon led the rush back into the bank. Grabbing up his hidden revolver, Nixon ran out into the street to give the alarm. Johnson the horse buyer meanwhile snatched the “pumping gun” off the wall, ran back into the yard and over the fence, and drew down on the robbers as they sped away on horseback.

But — click — the gun was empty.

Just then Deputy Sheriff George Rose ran out of the courthouse with a rifle in his hand. He raced past Lee and Slats and climbed a windmill that gave him a view over the slaughterhouse roof. Another spatter of popping broke out, and the boys followed him up the tower in time to see that the robbers were having a little trouble getting out of town.

Galloping down Second Street, one of them had seen Sheriff Charles McDeid standing outside the Reception Saloon and sent him ducking back inside with a pistol shot. They had taken the corner at Cross’s Creek full tilt and in the process the moneybag had slipped loose and fallen on the street scattering coins. The robbers hauled up their horses wheeled and plunged back to where the sack lay in the street. One of the men dismounted and handed it back up to a second man while the third man was attending to the pursuit with his six-gun.

Back at the bank, Johnson threw his “pumping gun” down in the alley in disgust and after George Nixon emptied his gun in the air, Calhoun, the stenographer, followed the robbers on foot. As Golconda’s newspaper, the Silver State, explained the next day, “He accidentally turned the corner where the men had dropped that sack and one of the robbers good-naturedly took three shots at Mr. Calhoun, who promptly fell behind the fence.

As Calhoun tumbled out of sight and the robber leapt back into the saddle, the door of the cottage behind the bandits opened. Chris Lane poked his head out and angrily began lecturing the horsemen about shooting off their guns inside the town limits. A bullet splintered the door frame over Lane’s head and he jumped back inside. The three men spurred their horses and dashed away leaving some of the gold coins glittering in the dirt where the bag had fallen.

The Chase

The pursuers on foot paused to scratch in the street for coins while the bandits raced out of town on the Golconda Road. Seeing them go, Deputy Rose climbed down from the windmill and hurried to a nearby railroad spur where he commandeered a switch engine and its crew to chase the rapidly departing bad men. When Lee and Slats climbed on too, Deputy Rose ordered them off and they had to jump down. But as soon as the deputy turned his back Slats scrambled back on board.

The robbers had a good lead on the locomotive, and at the Sloan Ranch about 8 miles out of town they changed over to fresh horses. In the process they took three fine saddle horses belonging to George Nixon, including his personal favorite. They galloped on with the little switch engines slowly gaining. Deputy Rose was poised at its nose waiting to get within rifle range and Slats Rutherford had his head down and his heart in his throat, hanging on at the back of the engine.

About 11 miles out of town Deputy Rose began lobbing shots at the fleeing robbers, and the Silver State the next day gave him credit for wounding one of Nixon’s horses. Nevertheless the barbed wire fence that kept the horsemen penned beside the tracks had been cut, and they sprinted north out of rifle range to another change of horses near their little camp by the river. There they transferred the gold to a packhorse and rode into the hills.

Posses were formed, trackers put on the trail and telegrams were sent to law officers in the surrounding districts. The chase was on. If the men dispatched from Golconda had taken a slightly different route they might have cut the trail ahead of the robbers. As it was they caught up to them as they were changing horses at Clover Valley on the way to Soldier Pass. The posse couldn’t keep up with the fresh horses but it did get close enough that one of the bandits stood up in his stirrups to yell back at them, “Give the white horse to the kid on the CS Ranch!”

They did, and for years afterward Vic Button rode his white horse Patsy all around that country.

The progress of the chase from Wednesday September 19 to Thursday September 27 is told in the headlines of the Silver State:

First National Bank Robbed

Three Desperados Loot It and Secure Thousands of Dollars

Cashier and Assistants Forced to Hand Over the Money to the

Robbers Who Afterward Escape With Their Booty

Robbers are hard-pressed

Last reports say posse was not far behind

Desperados Are Heading for Juniper Country —

News of a Fight is Expected Hourly

Chase of the Robbers

Were near Tuscarora last night

Strong Posse is Pursuing Them

Last News Received Indicates the Capture of Desperados

Robbers Still At Large

Posses Still After Them But There Is No News of the Chase

The Robber Hunt

Posse Still Following Them Through Wilds Of Northern Idaho

No Further News Of Robbers

Duvivier Returns

At last accounts posse was far behind robbers

Lost Trail of Robbers

Only chance of capture now is by posse from Idaho

After that nothing. The robbers had disappeared.

The Evidence

There was no lack of suspects. Even before the dust of the chase settled the Silver State printed a long roster of candidates. In describing the tail end of the chase a week after the robbery, the Silver State mentioned that “two hard characters from Wyoming” who had been around White Rock for some time are also believed to be connected with the robbery.

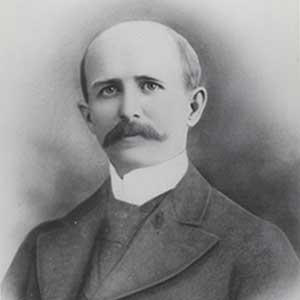

George Nixon pressed a vigorous investigation. He hired Tom Horn, the notorious enforcer of the Wyoming Cattlemen’s Association, and paid numerous informants. In correspondence with the Pinkerton Detective Agency Nixon guaranteed payment of $1000 for each of the robbers dead or alive, and said he would also commit one-fourth of the recovered loot, and even more if there were significant risk or expense involved.

About six weeks after the robbery someone got around to searching the campsite near the river and found the torn-up scraps of three letters which Nixon himself taped back together and sent to the Pinkertons.

One of the letters, postmarked September 1 1900 at Riverside Wyoming, was addressed to C.E. Rowe, Golconda Nevada. “Dear friend,” it said, “Yours at hand this evening. We are glad to know you were getting along well. In regards to sale, enclosed letter will explain everything. I am so glad that everything is favorable. We have left Baggs, so write us at Encampment Wyoming. Hoping to hear from you soon I am as ever, your friend Mike.”

Another letter was written on blue paper with the letterhead of attorney D.A. Preston of Rock Springs Wyoming. It was dated August 24 1900 and read, “My Dear Sir, Several influential parties are becoming interested and the chances of the sale are becoming favorable. yours truly D.A. Preston.”

The third letter was written in the same handwriting as the second and on the same blue paper but with no letterhead and no salutation. “Send me a map of the country,” it said, “and describe as near as you can the place where you found the black stuff so I can go to it. Tell me how you want it handled. You don’t know its value. If I can get hold of it first, I can fix a good many things favorable. Say nothing to anyone about it” was signed simply “P”.

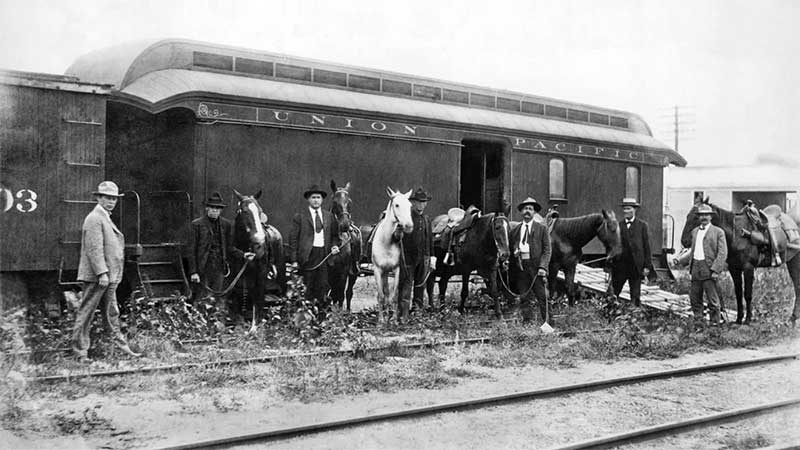

Douglas A. Preston was Butch Cassidy’s lawyer and had represented other members of the Wild Bunch in their scrapes with the law.There were other hints of a Wyoming connection. One of the getaway horses wore a Wyoming brand and was discovered to have been rustled. There were those “two hard characters from Wyoming” who reportedly met the robbers in the wilderness of southeastern Idaho and disappeared with them. The Photograph

The Photograph

A few years ago, two bound volumes of letters were found in the basement of the old bank building. They turned out to be copies of George Nixon’s business correspondence from February 24 1900 to October 9 1905. These letters were later given to Lee Berk, a longtime Winnemucca resident and ardent student of its history. In turn Mr. Berk passed them on to the Nevada historical Society. The letters shed light on a number of important events of the time and 28 of them are devoted to various aspects of the robbery.

One interesting aspects of the letters is that nowhere is there any suggestion that the famous photograph or any note or other communications had been received from the bandits. Mr. Berk read every issue of the Silver State for years after the robbery and nowhere had he found reference to the infamous photograph or the mocking note.

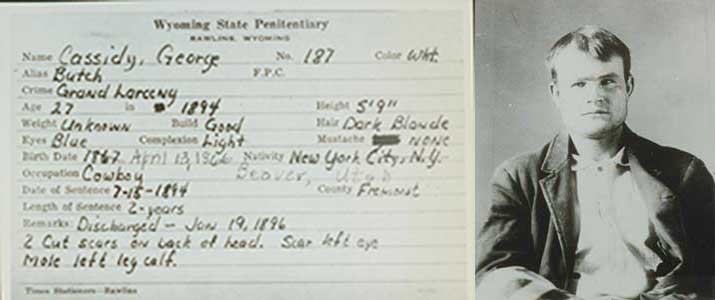

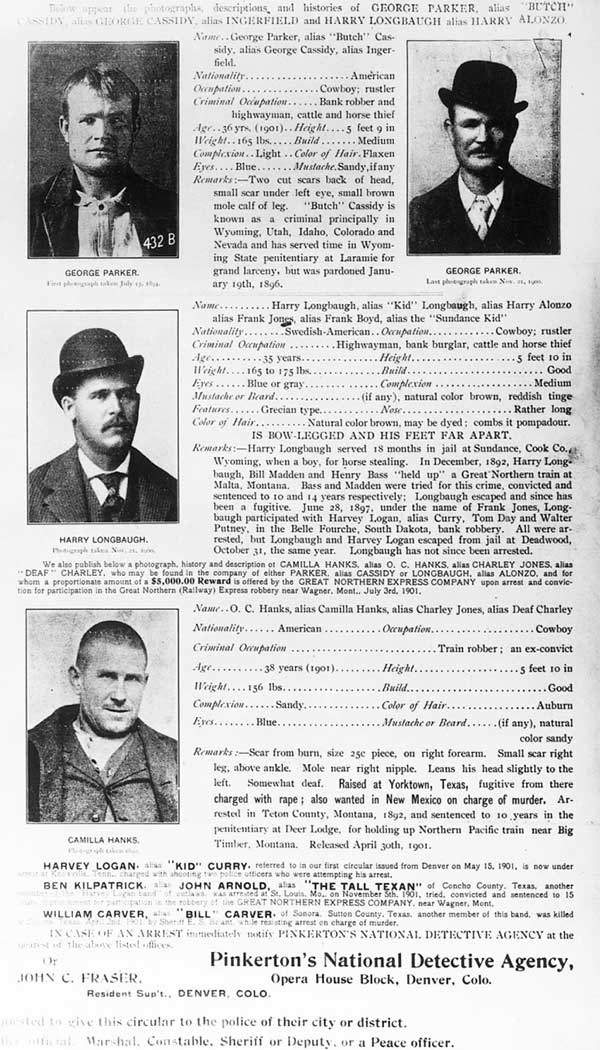

In fact it was the Pinkertons who sent George Nixon the photograph, about five months after the robbery took place.The photo was discovered by a Wells Fargo detective working undercover as a gambler in Fort Worth Texas to track down the survivors of the Black Jack Ketchum gang. The detective was strolling down Main Street one day when he happened to pass the Schwartz Photography Studio and noticed a picture on display of five dapper dudes in their new threads. He was startled and pleased to recognize the handsome young man standing on the left as Bill Carver, one of the men he was searching for. The others were quickly identified as Harvey Logan (Kid Curry), Harry Longabaugh (alias Harry Alonzo, alias the Sundance Kid), Ben Kilpatrick (alias the Tall Texan, another one of the Ketchum bunch), and Butch Cassidy.

Wells Fargo sent a copy of the photograph to the Pinkertons who were investigating the Winnemucca robbery on behalf of the American bankers Association. They sent it along with some mugshots for George Nixon in Winnemucca for his identification.

“While I am satisfied that Cassidy was interested in the robbery,” Nixon wrote in reply on January 8 1901, “he was not one of the man who entered the bank.”A month and a half later however, Nixon conceded, “So far as is Cassidy is concerned we will be willing to take chances in paying the reward for him upon the evidence now in hand.” But he emphasized that Cassidy had not been one of the robbers. “I am trying to get the description of Cassidy from a person who formerly knew him, as the photograph you sent me is the likeness of a man with a great deal squarer cut face and massive jaws, in fact somewhat of a bulldog appearance, while the man “Whiskers” struck me as a face that, in case it was shaven, would have more of a coyote appearance.

The famous photograph shows four strong chins. Only Harvey Logan looks like a coyote, and Nixon tentatively identified him. “After studying the photo of Harvey Logan which you sent me, Mr. McBride and myself are of the opinion that he is #2,” he wrote. As for robber #3, Nixon added with obvious hesitation, “I am also about confident now that he was Harry Alonzo.”

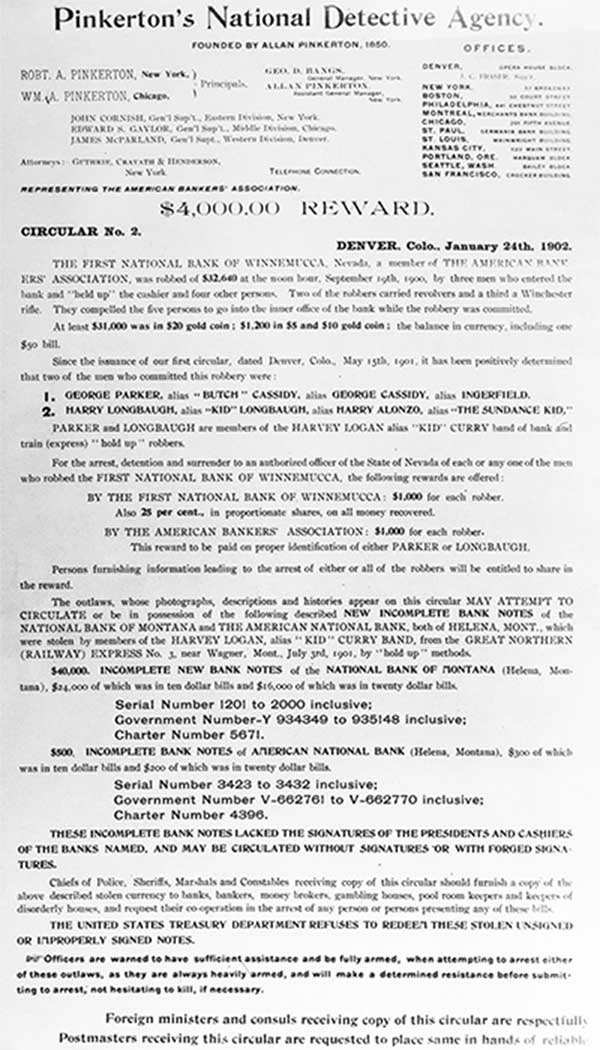

This seems scarcely a firm identification but on May 15 1901 the Pinkerton Detective Agency offered a $6000 reward for the arrest of the Winnemucca robbers. The flyer contained descriptions of the three men who entered the bank and stated: “After a thorough investigation and from information received, George Parker (right name*) alias George Cassidy, alias Butch Cassidy, alias Ingerfield and Harry Longabaugh, alias ‘Kid’ Longabaugh, alias Harry Alonzo, are suspected of being two of the men engaged in this robbery.

The Verdict

While the flyer was being distributed to law officers around the country, Butch, Sundance and Etta Place were in New York enjoying a farewell round of parties and pleasures before sailing to Buenos Aires and a new series of adventures in South America.

A Pinkerton detective eventually tracked them to Argentina but didn’t pursue them into the interior where they were ranching at Chulila in Chubut Province. When Butch and Sundance were reported killed by soldiers of the Bolivian army a few years later, the Pinkertons closed their files on them.

This much we know: Butch Cassidy didn’t rob the bank and he didn’t send that photograph.

The rest is theory but there is plenty of that. Lee Berk came to believe that some local person — C.E. Rowe perhaps, or one of the suspects listed in the paper, or someone whose name never came to light — recognized the bank as a plum ripe for the picking and got word to the Wild Bunch in Wyoming. Then some of the boys rode in to look the situation over, and later did the job. At age 91 Lee Case could plainly remember his shock and surprise at seeing his cowboy friends from the livery stable stampeding out of town in a blaze of gunfire, but he couldn’t recall that they ever mentioned their names.

Another persistent theory says that the robbery was an inside job and that George Nixon had conspired to rob his own bank. One variant of this theory has the horse buyer Johnson actually being Butch Cassidy himself, but Johnson was a real person, well known and well documented; an impersonation is out of the question.

Another version of the inside job theory has George Wingfield as mastermind. Wingfield, later a mining millionaire and political boss of Nevada, had appeared in Tonopah not long after the robbery with a grubstake provided by Nixon. He and Nixon were partners in numerous enterprises over the years after the robbery, including productive mines at Goldfield and a chain of banks. It is perhaps tempting to picture them scheming together to fake the robbery.

But Wingfield was already a well-known character in the region, having run a saloon in Golconda and raised horses on a ranch nearby. His comings and goings were noted in the newspaper; he could never have taken an active part in the robbery without being recognized.

And George Nixon was doing very well on the square, as he did all his life. Rich from his Goldfield speculations, he built a chain of banks around the state and a mansion on the Truckee Bluffs in Reno. In 1905 he ascended to the US Senate, the very model of material success.

Will Carver was shot and killed on April 2, 1901 while resisting arrest in Sonora, Texas; Kid Curry committed suicide near Parachute Colorado to avoid arrest on June 7, 1904; Ben Kilpatrick was killed on March 12, 1912 while robbing a train near Sanderson, Texas.

As noted, Butch and Sundance died in Bolivia in November, 1908. By this time Butch was famous for forebearance during his banditry. Unlike the ferocious and quick-triggered Harvey Logan, he wasn’t a sociopath and he never killed anyone.

Until the end.

The Bolivian soldiers searching for the payroll robbers were led to a small village where two Yanquis had recently taken residence. As Christopher Klein wrote in an article on History.com:

“As a Bolivian soldier approached the hideout, the Americans shot him dead. A brief exchange of gunfire ensued. After it subsided, San Vicente mayor Cleto Bellot reported hearing “three screams of desperation” followed by a single gunshot, then another, from inside the house. When the Bolivian authorities cautiously entered the hideout the following morning, they found the bodies of the two foreigners.

“The man thought to be the Sundance Kid was slumped against a wall with bullet wounds to his body and a gunshot to his forehead. The man believed to be Cassidy was next to him on the floor with a bullet hole to his temple. . . . . It appeared that Cassidy had shot his wounded partner between the eyes before turning the gun on himself.

“No-one was ever arrested for robbing the Winnemucca bank, and the reward was never paid.

*This is a curiosity, as Butch Cassidy’s true name was Robert Leroy Parker. The error is ‘corrected’ to George Parker in the Pinkerton flyer above and may have originated on the card from Wyoming State Prison up top.

*This is a curiosity, as Butch Cassidy’s true name was Robert Leroy Parker. The error is ‘corrected’ to George Parker in the Pinkerton flyer above and may have originated on the card from Wyoming State Prison up top.

Butch Cassidy was not involved the planning or robbery of the Winnemmucca Bank in 1900. In fact Butch and Sundance never did a robbery together in the US. They didn’t die in a shootout in South America. Butch died June 2,1956 and Sundance died June 2,1955. For the full details read the new book “Last of The Bandit Riders Revisited Again”