Sutro’s Tunnel Vision

Sutro’s Tunnel Vision

By David Moore

In the early 1860s Adolph Sutro, a 30-year-old Prussian who ran a cigar business in San Francisco, joined the rush to Virginia City and the Comstock Lode. Like most of the hordes of gold and silver seekers pouring over the Sierra, the Jewish entrepreneur had one goal: to strike it rich.

Sutro knew his strengths and limitations. He wouldn’t find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow with a pick and shovel but rather with his intellect and energy. At first, success in Nevada was elusive. A mill he operated east of Dayton burned down in 1863. He continued to sell cigars but yearned for a greater challenge.

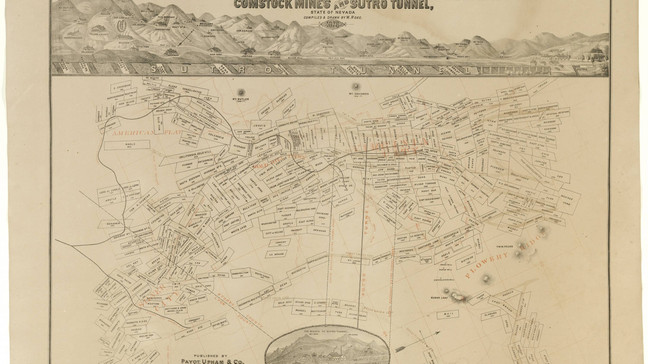

He found it with his next endeavor, the Sutro Tunnel, which made him famous as well as rich. His idea was to dig a tunnel to drain the hot waters that plagued the Comstock mines. Between 1869 and 1878, starting on a small ridge northeast of Dayton, workmen dug nearly four miles through the mountain, aiming slightly uphill, to reach the Savage, the Con Virginia, and other Virginia City mines.

Sutro’s tunnel vision included an adjacent town laid out with streets and parks. Perhaps 800 people lived in Sutro at the height of the tunnel’s construction. Many residents read the local paper, the Sutro Independent, and picked up their mail at the Sutro post office. Adolph Sutro lived in a mansion overlooking the town and Dayton Valley. His wealth slowly grew. After the tunnel’s completion, Sutro became rich by selling his stocks. He moved back to San Francisco, became a real estate titan, and was elected mayor.

Meanwhile, activity diminished at the tunnel. By the mid-1900s, the Sutro site was essentially a ghost town.

Today, the old town retains its share of wooden buildings and weathered machinery, but the surroundings have changed. Now it rubs elbows with another, vastly larger community, the growing modern-day Dayton suburbs. Single family homes ring the neighborhoods, and Sutro Elementary School is just a few blocks away.

The historic site of Sutro, however, is not forgotten, as demonstrated by a series of tours presented by the Friends of Sutro Tunnel. The group was formed by a cadre of Nevada ghost town enthusiasts six years ago to help rehabilitate and advocate for the Lyon County landmark (see thesutrotunnel.org). The Friends’ stated goal is to restore Sutro in a way that is as historically accurate as possible and to make the site safe for visitors. The Friends are planning a host of ghost and regular tours to raise interest and funds to support Sutro’s restoration—their own tunnel vision, you might say.

The Friends of Sutro Tunnel held such a tour on the crisp, clear morning of Saturday, February 12. While two dozen history buffs shuffled their feet in the dust of the Friends’ small but packed parking lot, project manager Chris Pattison told them, “This is the first tour of the year, and we hope eventually to host a tour every month. Recently we announced online that we were holding $125-per-person ghost tours later this spring, and they sold out in two days.” As the crowd murmured in appreciation, he added, “So you can see there is a lot of interest in Sutro.”

The day’s tour was organized with the help of the appropriately named Tami Force, who leads the Carson City-based website Nevada Ghost Towns and Beyond. “I’m working to bring everyone out and spread the word about the Sutro Tunnel,” the energetic Force said. “The work of volunteers here from last April to December has been amazing.”

The tour guides were Patrick Neylan of Dayton and Dan Webster of Carson City; both are members of the Friends of Sutro Tunnel. More than 20 people followed the tour at times. Some were Friends; others included the curious and the historically informed, such as Dennis Cassinelli, whose columns on Silver State history appear in the Nevada Appeal.

The tour guides were Patrick Neylan of Dayton and Dan Webster of Carson City; both are members of the Friends of Sutro Tunnel. More than 20 people followed the tour at times. Some were Friends; others included the curious and the historically informed, such as Dennis Cassinelli, whose columns on Silver State history appear in the Nevada Appeal.

Dan Webster, the author of the authoritative book Mills Along the Carson River, led the first half of the tour. He said, “I’ve been exploring ghost towns for years and knew about Sutro before I moved here. I’m always doing more research.” He explained that the surface of the 28-acre Sutro site has been turned over to the Friends of Sutro Tunnel Charity by the Serpa family of Carson City and Comstock Mining Inc., which controls the former Leonard family property. The Friends of Sutro Tunnel is now a 501(c)(3) charitable organization.

Gesturing to the building next to the parking area, Webster said, “This was the carriage house. People used to live there. It’s our next big project. We plan to clean it out, do repairs. We also plan to make a parking lot so people can park more easily.”

Next stop was a weathered but handsome Victorian house that once stood in Carson City. Webster said, “The house was moved here in the 1970s. We will try to preserve it even though it is not original.” Another structure hauled to Sutro from Carson City was Rosa May’s house, named after a prostitute who worked in the capital’s long-gone red-light district on Curry Street.

Webster pointed out the now spiffy Sutro wood shop. “We power-washed the floors and cleaned it out,” he said. “Most buildings were just left, and rodents and pigeons moved in there.”

Volunteers have placed a collection of mining and milling equipment along the south side of the roadway that circles the former shop areas. A wooden bailer from the early days, with a diaphragm at the bottom, was the first way to take water out of the shafts along the tunnel. A Pelton wheel, made of iron steel, was a high-tech water wheel. Various machinery was used in the mill built in 1900, after Adolph Sutro’s time.

“When I was here in the ’70s, most of the machinery was down where the mill was,” Webster said. “The last time the mill was running was in the late 1930s or early ’40s.”

One of the best preserved buildings was the mule barn. Webster said volunteers found the barn’s roof was sagging severely, but they lifted the roof with a wonderful result. “When we straightened it out, the stable and everything came back into place.” Duck inside, and you’ll see eight stalls neatly lining the right wall.

A warehouse, built 1872, held supplies. Visitors of the 1960s and ’70s may remember this building as the rustic Sutro Saloon and occasional dance hall, birthplace of the famous rock band Sutro Sympathy Orchestra. Alas, the Friends plan to return the warehouse to its original tunnel era condition.

Near the portal, Webster urged tour goers to note an odd cut in the ledge that served as an icehouse. He pointed out a row of ore cars. “While working on the ore cars we saw that some of the wheels were cast in the Virginia and Truckee Railroad foundry at the old roundhouse in Carson City. They are truly historic.” And there was an “electric mule,” as tunnel workers called the battery-powered engine used in place of mules in the 1920s. Webster added, “When you see this, you realize that electrically powered cars are not new.”

Patrick Neylan led the tour to the tunnel portal. Peeking inside, you could see how rocks and timbers had caved in near the entrance.

“Sutro Tunnel is 3.88 miles long,” Neylan said. “The workers cut the tunnel so it gained an inch every 100 feet, so the water would flow in this direction. The slope also made it easier on the mules, who carried supplies into the tunnel and full ore cars out. Why is the tunnel here? Sutro and his men studied the area and decided this was the only point from which the tunnel would meet the Comstock mines at the 1,600-foot level. No matter how you look at it, the Sutro Tunnel was truly one of the engineering marvels of the 19th century.”

Neylan noted how, in 1865, Adolph Sutro went to the first session of the Nevada legislature and was granted permission to raise funds to build the tunnel. But he needed a federal OK as well, which Congress granted in 1866. Sutro was granted 2,000 feet left and right of the tunnel’s route all the way to Virginia City. He could mine non-claimed spots. But he never made anything from the ore. Fundraising delays worked against him, Neylan said. “If the tunnel had been dug five or 10 years earlier, it would have changed the whole industry.”

One night in September 1869, five months after the terrible Yellow Jacket fire in Gold Hill that killed 37 miners, Adolph Sutro rented Piper’s Opera House in Virginia City and gave a stemwinder of a speech. He said the miners could have escaped the fire had the tunnel been dug. As a result the unions gave Sutro $50,000, and on October 19, 1869, he finally began work on the tunnel, with a promotional twist. Sutro hired nine men to work around the clock in three-man crews, allowing him to announce: “Now operating 24 hours a day.”

Eventually hundreds of men worked on the tunnel, but it was slow going. The pace picked up in the 1870s when crews started using pneumatic drills. Neylan said, “Sutro hired drill operators who had worked on the Hoosac Tunnel in northwestern Massachusetts. At 4.75 miles the Hoosac Tunnel was the longest railroad tunnel in the country for many years. Soon Sutro’s crews were averaging 300 feet a month.” Heat was a problem. So was the tedium. Neylan noted, “You can imagine how boring the work must have been, when three three-man teams would work all day and all night and advance only 10 feet.”

The timing of the tunnel’s completion was inauspicious, however, as 1879 marked the last big year of full production in the Comstock mines. Neylan noted, “Sutro very quietly sold off his stock for $907,000, which gave him a good bankroll to take to San Francisco.”

As the tour approached noontime, Neylan led a dozen people up the hill to the site of the Sutro Mansion, which burned down in 1941. “Sutro moved here in 1872, three years after work on the tunnel began,” Neylan said. “He didn’t pay for the mansion himself. It was built by the Sutro Tunnel Company under his expense account. He outlined what kind of a residence he wanted: large, airy, well heated, able to handle the snow load. Cost of the three-story mansion was $40,000, and it was built in just a few months. It was big—1,600 square feet on the first floor, so more than 5,000 square feet in all, plus a cupola on top. The house had flush toilets and a unique water system. They had found a freshwater source in the tunnel, so the mansion was piped with hot and cold running water. Sutro’s family was here for Christmas 1872.”

The family stayed at the mansion off and on until former President U.S. Grant’s visit to Sutro in 1879. During the festivities Sutro’s rocky relations with his wife, Leah, reached a donnybrook. As soon as Grant’s party left the mansion, Leah Sutro packed her bags and took the children to San Francisco. Afterward Sutro was removed from his position, and neither he nor his wife ever returned to Nevada.

Following Sutro’s departure, his younger brother Theodore was appointed superintendent and managed the site until 1898, the year Adolph died. The company was then sold to Franklin Leonard, Sr., whose family operated the tunnel, surrounding mines, and site until the War Production Board’s executive order L-208 shut down “nonessential” mines during World War II.

Besides the tunnel, Adolph Sutro’s other great dream was the town of Sutro. According to Neylan, Sutro laid out 50 numbered streets east and west; 27th Street, extending east from the tunnel, was renamed Tunnel Avenue. In the other direction, streets were named for women, from Adele to Zeline. When you bought a lot, you had to buy a tree and plant it.

After the tunnel broke through to the Virginia City mines, Sutro employed more than 1,000 men to carve out the laterals and water tunnels. The town’s population reached 800 to 900 souls. However, once the tunnel was completed, Sutro laid off workers. Residents left and the desert hamlet withered.

“The town site extended all the way from the tunnel to where Highway 50 is today,” Neylan said. He recalled, “In the early 2000s I used to ride my bicycle through the old town site and see remnants of the streets, tree stumps, foundations, and broken glass.”

Near the tour’s end, Neylan looked south across Dayton Valley. He mused, “If Sutro could stand here today, he could look out toward the highway and finally see his second dream taking shape.” The tour group watched as huge earth movers scraped away the sagebrush covering the old town of Sutro, making way for hundreds of new homes.

——

See thesutrotunnel.org for online information about the Friends of Sutro Tunnel, their tour schedule, and opportunities for volunteers. The Friends of Sutro Tunnel also can be contacted at P.O. Box 1264, Carson City, NV 89702; phone 775-882-7777.

——

David Moore is former editor of Nevada Magazine.

[…] NevadaGram last visited the Sutro Tunnel in February 2022, readers accompanied the intrepid reporter David Moore and our own Robin Cobbey on a vicarious […]