Jarbidge Nevada lies within the narrow steep sided canyon that’s the channel for the middle Fork of the Bruneau River, 9 miles south of the Idaho border in the northeast corner of  Nevada at 6,500 feet above the level of the sea. Sharply rising walls of rock soar up on either hand to jumbled spurs and crags more than 2,000 feet above the tiny gold rich settlement below. Summer nights are cold — there are places where the ice never melts — and the winters are eight months long.

Nevada at 6,500 feet above the level of the sea. Sharply rising walls of rock soar up on either hand to jumbled spurs and crags more than 2,000 feet above the tiny gold rich settlement below. Summer nights are cold — there are places where the ice never melts — and the winters are eight months long.

Today the population totals a couple of dozen but in 1916 jarbidge was one of the busiest and most productive mining camps in Nevada with hundreds of people busily engaged in getting rich, or at least staying alive.

Postmaster Scott Fleming loosened his high starched collar and stared apprehensively into the lacey curtain of snow falling on Jarbidge’s single street. December had been stormy and snow had been falling steadily since the early afternoon of the fifth. The stagecoach bringing the mail down from Rogerson Idaho was already three hours overdue and Fleming was worried. With three feet of snow in the higher passes, he knew it took all the skill and stamina the driver possessed to hold his horses to the narrow Crippen grade.

Earlier he’d watched a string of laden wagons rattle into Jarbidge, the red-faced stiff-limbed drivers sitting high up on the boxes, hurrying their exhausted teams up the narrow canyon street. They had met an outbound train of empty wagons at one of the narrowest points of the grade and been forced to spend the previous night and half of today struggling past one another on the freezing flank of the mountain. Fleming was beginning to think the stagecoach might’ve met the same wagons before they crested the Summit.

At a little after 8 o’clock a miner named Frank Leonard was checking his mail at General Delivery and registered surprise when Fleming told him the mail had not arrived. The outbound drivers had called in from the telephone at Rattlesnake Station at the summit of the Crippen Grade, Leonard told him. They said they had passed the stagecoach on its way down to Jarbidge at mid-afternoon. It should have been in town well before now.

Something was seriously wrong. Fleming pictured driver Fred Searcy plunging over the edge of the snow-slick road. Immediately he hired Leonard to ride up the Crippen Grade and bring the sack of registered mail back with him if he could retrieve it from the wreckage.

When Leonard returned some two hours later, the small post office was filled with concerned men whose buzzing speculation stopped abruptly as he entered. He described a bitterly cold ride through the blinding snow all the way to Rattlesnake Station and no sign of the stagecoach. One of the men suggested a search party and was met with a willing chorus of approval.

“Wait a minute now,” Fleming interrupted. “We know Fred got to the summit and we know he’s not on the road now. Before we go running half-cocked into that blizzard let’s see what else we can find out.” He plucked the telephone receiver from the wall, rotated the crank and asked the operator to ring Rose Dexter, who lived in the last cottage in Lower Town, the straggling collection of shacks and lean-tos across the river.

“Why, yes,” Mrs. Dexter said, the stage had passed her house on the way into town. It had been about 6:30 she remembered, because she heard someone shooting at coyotes and had gone outside to warn them away from the house just as the stage had come around the bend from Rogerson.

She knew Fred Searcy of course. She had called up to him — “but he was bundled up with a heavy lap robe or mail sack across his legs and hadn’t answered,” she told the postmaster. “Probably frozen clear through and in a hurry to get to the barn.”

As Fleming turned toward the curious faces, the door burst open to admit a swirl of snow, along with a frosted giant of a man who stopped in surprise at seeing so many men crowded into the small building. His astonishment increased when he learned that the mail stage had not arrived.

“The hell! I saw the stage three hours ago, not a hundred yards from where I’m standing now!”

Editor’s Choice —

Las Vegas May Soon Get an Art Museum

by Joey Lovato

People bustle about outside the Las Vegas Container Park on a Sunday afternoon, flanked by flashy murals that stretch up to four stories tall. A giant praying mantis sculpture looms above the scene, blowing fire every few minutes toward the visitors below.

On the Strip, flashing billboards and street performers stand in front of immaculate fountains and imaginative casinos. Just a few miles outside of town there’s the Seven Magic Mountains art installation, which attracted about 120,000 people last year.

Further into the desert north of town, looking down on the ghost town of Rhyolite, are haunting statues of desert ghosts by Albert Szukalski. And farther still outside of Goldfield are graffiti-covered cars with their noses buried in the dirt — the International Car Forest of the Last Church.

Southern Nevada, a bastion of artistic attractions, remains one of the largest metropolitan areas in the U.S. without an accredited art museum.

Southern Nevada, a bastion of artistic attractions, remains one of the largest metropolitan areas in the U.S. without an accredited art museum.

But that could all change soon.

How Virginia City Became An Old West

Tourist Draw

by Alicia Barber

Today, Virginia City, Nevada attracts more than two million visitors each year. But that wasn’t always the case. In this segment of “Time & Place,” Alicia Barber explains how early promoters helped turn the historic mining town into a national tourist destination.

In the warmer months, C Street in Virginia City is jam-packed with tourists who cannot get enough of its historic western charm. It’s a far cry from the years prior to World War II, when the town seemed practically abandoned. Once the largest community in Nevada, Virginia City had been losing population ever since the mines of the Comstock began to decline back in the 1880’s.

In the warmer months, C Street in Virginia City is jam-packed with tourists who cannot get enough of its historic western charm. It’s a far cry from the years prior to World War II, when the town seemed practically abandoned. Once the largest community in Nevada, Virginia City had been losing population ever since the mines of the Comstock began to decline back in the 1880’s.

By the 1930’s, the town had only a few hundred residents, but some saw the potential for a new bonanza. Tourism was on the upswing in nearby Reno thanks to the state’s legalization of gambling and the six-week divorce. Visitors just needed to be persuaded to make their way up to the Comstock.

5 Years Ago in the NevadaGram

While we’re in a reflective mood, let’s remember that 2014 was Nevada’s 150th year, and that we actually got some pleasure from celebrating it. There were 500 sanctioned events of all kinds over the course of the year that ended on Nevada Day, October 31, and they took place all over the state.

While we’re in a reflective mood, let’s remember that 2014 was Nevada’s 150th year, and that we actually got some pleasure from celebrating it. There were 500 sanctioned events of all kinds over the course of the year that ended on Nevada Day, October 31, and they took place all over the state.

Read it All Here

Overheard at the Artisan Cafe in Carson City — “If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.

10 Years Ago in the NevadaGram

Season’s Greetings

from the Las Vegas Ski & Snowboard Resort

and all of us at the Nevada Travel Network

15 Years Ago in the NevadaGram

The 20th annual Governor’s Conference on Tourism ran its brief course at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Twenty years ago I was one of the half-dozen Tourism staffers scurrying around the Riviera Hotel in Las Vegas seeing to the needs of 317 attendees at that first Conference, a large proportion of them government employees.

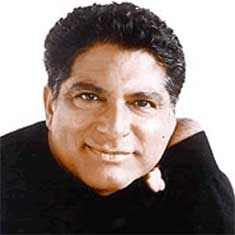

This year there were about 800 on hand, down somewhat from the pre-9/11 high of about 1000. Governor Guinn delivered a speech, Lt. Governor Hunt announced a new Nevada office opening in Beijing in 2004, and there were presentations by the Usual Suspects. But it wasn’t the Tourismic oratory that made this Conference exceptional, it was Deepak Chopra.

When I’d seen his name on the agenda I’d wondered what in the world he had to say to us about Tourism. The answer turned out to be: nothing.

When I’d seen his name on the agenda I’d wondered what in the world he had to say to us about Tourism. The answer turned out to be: nothing.

That’s what was so great about it. He spoke instead about overthrowing the superstition of materialism, of the way the human mind exists in every cell of the body, and how coincidence is a glimpse of the universal mind. He delivered us into a realm of science-based spirituality, far more interesting than we had any right to expect, and light-years beyond the bottom line.

Read It All Here

Parting Shot —

Virginia City after a midsummer thundershower

Virginia City after a midsummer thundershower