“There were many practical jokers in the new Territory. I don’t take pleasure in expressing this fact, for I liked those people; but what I am saying is true. I wish I could say that they were burglars or hat-rack thieves, or something like that, that would be utterly complementary.”

— Mark Twain in “Roughing It”, 1872

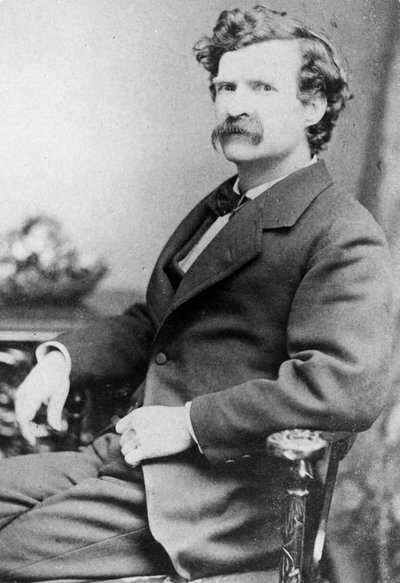

When Mark Twain was a reporter for the Territorial Enterprise named Sam Clemens, he was 27 years old, rumpled, unwashed and uncouth. More than uncouth he was rank, with a wildness that was never completely tamed, and which eventually made him one of the great figures in American literature and one of the funniest men we have ever had among us.

But he couldn’t take a joke.

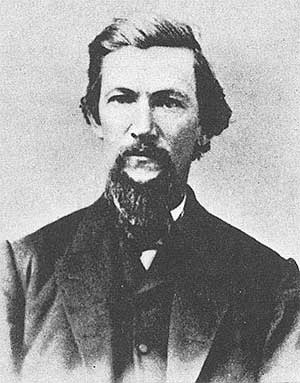

In those early Virginia City days, before his humor became legendary, he was considered crude and insensitive. Where Dan De Quille’s newspaper hoaxes were so graceful and credible that they were swallowed with ease, Twain’s were violent and rough. His tale of the 300-year-old petrified man found thumbing his nose in a Humboldt County creekbed was intended to insult the local Justice of the Peace as much as to amuse Enterprise readers. The famous Empire City Massacre hoax was a gory fantasy of multiple murders. It was believable (and believed, at first) despite the obvious confusion of geography and numerous other details, because of the enormity of the story and the intensity of its telling.

Twain’s prankish attitude toward the news columns of the Enterprise ultimately led to a duel and his abrupt departure from Nevada Territory. In the meantime he had helped to establish the newspaper hoax as a part of Nevada’s unique journalistic tradition.

Yet Mark Twain never thought it was funny when the laugh was on him. Maybe that’s why his friends found it irresistible to make him the butt of a joke.

In the autumn and winter of 1863 Twain shared a room in a B Street boarding house with his colleague Dan De Quille. The same house also provided lodging for Rollin Daggett of the Enterprise and for editor Tom Fitch of the rival Union and his wife Anna. Clemens thought it was a great joke to feed his stove from the Fitch woodbox, and when the Fitch cat disappeared he thought it was even funnier to say that he and Dan had hanged it.

When the wandering pet returned unharmed a few days later the Fitches were relieved but not amused, and when the opportunity presented itself for revenge, they grabbed it. Fitch told a story in a series of reminiscences he wrote for the San Francisco Call after the turn of the century (published in book form by the University of Nevada Press, edited by Eric Moody).

“One Christmas eve all of us except Mark were seated in the smoking room awaiting the announcement of dinner,” Fitch wrote, “when there arrived a lad with a package for Mr. Clemens, which he was directed to take into the smoking room. After his departure we examined the bundle, for we were communists in spirit, and found that it contained a pretty knitted woolen scarf and a card bearing the inscription, ‘Mr. Samuel L Clemens, from his friend Etta.’

“I can improve on that message,” suggested Daggett, who was the wag and philosophical disputant and cribbage player of the club, and obtaining a sheet of notepaper he wrote in a fine female hand the following note:

“’Mr. Clemens, the accompanying scarf having been prepared as a Christmas gift for you, it has been determined not to divert it from its intended destination, although a knowledge of your late conduct has come to the ears of the writer. Your own conscience will tell you that this must close all communication between us, in which decision my mother and father concur. Your former friend, ETTA’

“The scarf was rewrapped, and with this note tied to it was placed in Sam’s room. Shortly afterward he made his appearance and proceeded to his room to prepare for dinner. Soon we heard the crockery going. ‘What is the matter Sam?’ asked Daggett.

“Thereupon entered Mark Twain, with coat and collar off, and, throwing the package on the table he burst forth: ‘Read that!’ said he, flourishing the note from Etta. ‘Read that! That’s just my infernal luck! You hounds can run the town night after night and nobody ever says a word, and I am found out at once.’”

Fitch’s pleasure in the revenge is still obvious nearly 40 years later. Joe Farnsworth the former state printer who worked for the Enterprise in his youth, said that Twain was despised in Virginia City and that the jokes played on him were meant to hurt. Certainly Twain rubbed plenty of people the wrong way, but it is clear that most of his close associates were quite fond of him. Especially Dan De Quille, who partnered with him. Dan was at the center of perhaps the cruelest joke of all, and the only one that seems to deserve Farnsworth’s description.

This story is told best by Alf Doten, himself a Comstock newspaperman for more than 20 years, first as local reporter for the Union and the Enterprise, and eventually as proprietor of the Gold Hill Daily News.

“When Mark Twain was working on the Enterprise with Dan De Quille in the local department, those wicked printers played a Joke on their friend, the humorous Joker. They bought a clay imitation meerschaum pipe, big as a man’s fist, for four bits, got a tinsmith to mount it with tin in silver regulation style, finishing up with a long cherrywood stem and mouthpiece, the whole rig costing about $2, yet looking to be worth about sixty. Then they got Dan to quietly post Mark, who as quietly proceeded to smuggle a few bottles of champagne and some cigars into the office ready for the surprise party.”

“That evening the printers joined Dan and Mark in the local room and the magnificent pipe was presented. Mark, feigning surprise gave a humorous little speech in response, which he got off in good style, thanking his admiring friends for their rich gift, emblematic of appreciation of his humble efforts, assuring them that this noble journalistic pipe of peace should be fondly smoked through all future generations of the Twain family, in cherished memory of this auspicious event.

“’Say Dan,’ said he, ‘isn’t there a bottle or two of that wedding notice wine kicking around under the table somewhere?’ Dan found it, and there was much typographical and reportorial hilarity for a short time, while the wine and cigars lasted. Then Dan carefully wrapped and tied up the pipe and Mark took it proudly home.’

“When Twain arrived at work the next night, he was silent and brooding. Finally he confronted De Quille, charging him with complicity in the charade. ‘The wine and cigars cost me 60 times what that cussed smokestack is worth, to say nothing of my chuckleheaded speech,’ he ranted.

“;Jokes are jokes, but I don’t recognize this as one. I’ll be cussed if I do.’

“What he did with that remarkable pipe nobody ever knew,” Doten said, “but it was never heard of afterward, and any allusion to it brought an ominous scowl to his countenance, as sufficient warning to desist.”

Mark Twain left Nevada in 1864. He worked for a while as a reporter in San Francisco and then spent several months in the Mother Lode country of California before sailing for Hawaii, then still called the Sandwich Islands. Upon returning to San Francisco he launched himself as a lecturer on the subject of this Island paradise. Twice he returned to lecture on the Comstock, enthrallling audiences in Virginia and Gold Hill. His old friends took the occasion of his second visit in 1868 to make one final joke at Twain’s expense.

According to Steve Gillis, one of Twain’s greatest pals out west, an Enterprise typographer and the main instigator of the joke, the plan was hatched over Twain’s hugely successful lecture at Piper’s Opera House. Dozens had been turned away from the sold-out theater, and Twain’s exuberant friends urged him to schedule a second performance in Virginia City. But he refused, saying he would talk once more at Gold Hill and then head back to the coast.

It was then that Gillis was illuminated by the brilliance of his plan. He went at once to Denis McCarthy, an owner of the Enterprise when Twain was a reporter there, and now his road manager.

“The idea was to hold up Mark on the Divide when he should be returning, and rob him of every cent,” Gillis recalled. “The robbery would create a tremendous sensation, and if we could keep the secret from Mark, and pursuade him to give his version of the outrage, we could pack a pipers opera house at $2 a head.” McCarthy jumped at the plan like a hungry trout at a fly. “And just think what an advertisement it will be for Mark,” he said.

Dan De Quille and Joe Goodman were kept in the dark about the affair, Goodman because he would certainly refuse to permit it, and De Quille because the conspirators thought he would write it up better for the paper if he thought it was true.

As Gillis tells the story, “A little before it was thought Mark would have finished his lecture, the robbers marched out onto the Divide, all wearing black masks. But we had started too early, and as it was a very cold night so we worried that if Mark didn’t show up pretty soon the band would freeze. After waiting about an hour I was sent on ahead to Gold Hill armed with a policeman’s whistle, with instructions to sound it when our victim should get within 100 yards of the ambush.”

The eager Gillis tiptoed through the frosty darkness, reaching Gold Hill’s brightly lighted Main Street just as Twain and McCarthy stepped out the front door of the Miners Union Hall. He hurried back up the hill and burrowed into the sagebrush where he had a good view of the foot-path.

“When the proper distance was reached,” he wrote, “I loudly blew the whistle, which caused Mark to observe to his agent, “Well, I am glad they have a policeman on the divide, they never had one in my time.”

As Twain and McCarthy reached the crest of the Divide, the bandits rushed out from behind a little cabin where they had taken shelter from the freezing wind, and their leader gave Mark a look down the barrel of his six-shooter while ordering hands up.

“Mark’s hands went up,” Gillis wrote. “‘Now give me your watch and money — quick!’ demanded Bill Eddington.

“Mark lowered his hands to comply, when Eddington fiercely exclaimed, “What?! Going for your gun are you? Do you want your head blown off? Throw up your hands!”

“Mark’s hands again pointed skywards and Eddington repeated, ‘Now give me your money!’

“But it was plain Mark’s temper was rising for he angrily replied, ‘How in hell can I give you my money when my hands are up?’”

After compromising by rifling Twain’s pockets himself, and relieving him of his money and an engraved watch, the bandit chief sent his men back into the shadows of the cabin with orders to shoot the two man dead if they attempted to leave the place before 15 minutes have passed.

Twain and McCarthy waited twice the required time, and then they hurried the rest of the way into town. Gillis had meanwhile collected the loot, sent the bogus bad men home, and planted himself on a barstool in “the first big saloon on C Street that Mark and his agent would have to pass, knowing that their half-frozen condition would drive them into it to get warm. Sure enough, in they came.”

Twain described the affair as if it had been a minor annoyance, but Gillis insisted that three of them makes straight for the Enterprise office. Dan De Quille was just finishing up writing the day’s local news, and at Gillis’ urging he wrote a spirited account of the robbery for the morning paper. Twain meanwhile, wrote out an ad offering a reward for the return of his valued gold watch, no questions asked.

Having dealt with the formalities, Twain suggested that they go out and run with the boys. But in order to stand his share of the drinks Mark was compelled to borrow $80 from his old friend Gillis, who magnanimously supplied it.

In order to cover his losses Twain then agreed to another performance at Piper’s. But on the evening before the performance he paid a visit to Judge Baldwin, who had presented him with the gold watch that was taken. The disappointment he expressed over the loss of the watch was so obviously sincere that Baldwin felt compelled to tell him that this stickup had been a joke and that the watch would be returned.

Twain returned to Joe Goodman’s house in a fury. The more he thought of his humiliation at gunpoint in the freezing darkness, the more he burned with anger. Goodman sat up half the night with him, talking him out of filing a criminal complaint. Twain relented, but he canceled the second performance at Piper’s and bought tickets on the next stage coach out of town.

“The dejected robbers were all at this stage station to see Mark off, and, if possible to placate him,” Gillis remembered. “But all attempts in that direction were received by Mark with cold disdain. Instead he denounced that sorrowful gang in withering words of hostility. He told them that he knew now who had committed the numerous robberies in and around Virginia City; that they might claim this robbery was a joke but from the professional manner in which they performed it, he was certain that they were guilty of many others which were not jokes, and predicted that all of them would finally land in the penitentiary.

“He refused to shake hands with any of them, or even to bid them goodbye.”

Later on Alf Doten heard the rest of the story from Denis McCarthy. “McCarthy told afterword,” he wrote, “that for the first 10 miles Mark was too deeply occupied with bitter reflections to say a word but finally he said, “Denis McCarthy, was you a party to this thing? Did you know anything about it?”

“Denis mildly acknowledged that the boys had hinted to him a few points in the matter, but he had no idea they would carry the joke so far. It took a lot of soothing talk, explanation and reasoning, but Mark never seemed to be entirely reconciled.”

Indeed, as Twain tells the story in Roughing It, he insists that the jokers got the worst of it, on account of waiting for him in ambush for two hours in the dark and freezing cold.

But then resentment awakened within him and he peevishly complained that the sudden sweat in the frigid night gave him a cold “which developed itself into a troublesome disease and kept my hands idle some three months, besides costing me quite a sum in doctor’s bills.

“Since then,” he added — and these are the final words of Roughing It — “I played no practical jokes on people and generally lose my temper when one is played on me.”

Originally published in the Fall 1979 edition of Nevada Magazine