I was driving north out of Carson City on a bitter cold night last February with a broken headlight and the fresh air vent jammed open, sipping at a can of beer when the Highway Patrol pulled me over.

I put the beer can on the floor and fished out my drivers license and registration for the patrolman, who looked them over and returned to his patrol car. When he returned he said, “Mr. Toll, I stopped you because one of your headlights is out.”

“Yes,” I lied. “I noticed it when I turned my lights on a while back.” He had me step on the brake, switch on the windshield wipers, run through the whole repertoire, and when it all check out you Came back to my window and said, “Mr. Toll, everything else seems to be working all right. Tell me, how much of that beer have you been drinking?”

“Beer?” Oh, Christ. “Why, none.”

“Lift up that can by your feet.”

I lifted it up.

“Hand it to me, please.”

I handed it to him.

“Get out of the truck, please.”

I climbed out, thinking that at least it was early enough call my lawyer when we got to Jail, trying to remember how much cash I had in the bank, and wishing to hell I never got out of bed that morning.

The patrolman walked me to the car and had me stand facing it, between the headlights, place my hands flat on the hood, spread my feet apart and maybe three feet back from the front bumper, so that my weight rested on my hands. He patted me down, armpits to ankles, before he let me straighten up again. Then he poured the rest of the beer out onto the icy ground. I stood there shivering, bathed in the cold glare of the patrol car’s headlights as the highway traffic flashed past us, bursts of dazzling light streaming through the freezing night: honest citizens on their way home to bed.

“Mr. Toll, you lied to me. Why did you do that?”

I stopped lying: “Because I didn’t want to be arrested.”

“Well, let me tell you something. I don’t know what your experience has been with Highway Patrolmen in other states,” he paused to look at my shoulder length hair blowing fitfully in the cold breeze off the Sierra, “but in Nevada we do things a little differently. If you play straight with us, we’ll play straight with you all along the line. I can see you’re not drunk. I followed you long enough to know you aren’t driving recklessly, and you only had the one can of beer in your pickup.

“But you lied to me, and when you start lying, I have to wonder what else you might be covering up. I’ve checked you out and you’re clean. So I’m just going to give you this mechanical defect citation. There’s no fine, but you have 10 days to get that headlight fixed, get the card signed by any law-enforcement officer, and put it in the mail to Carson City. But I also want you to remember that lying to a Nevada Highway Patrolman in a situation like this is futile and just creates trouble for yourself. Don’t forget it. Good night now.” He handed me the citation postcard, got back into his patrol car, and drove away into the night.

His words were still hanging in my truck as I drove away, and my own “Thank you” was in there too. Imagine being pulled over by a policeman and saying thank you when you drive away. And meaning it.

I have been stopped by highway patrolman in other states, and I was flabbergasted at being treated decently and fairly. I suppose I told that story a dozen times or more to my friends, some of whom have more hair and beard than I do, people you’d figure would get the full brunt of any weight a Highway Patrolman would want to throw around. I expected surprise and incredulity, but I got agreement instead. Everyone I talk to who had been stopped by a Nevada Highway Patrolman has something good to say about them. I didn’t find anyone who had been hassled or shoved around, even when they had drawn a ticket. In other states, yes, but not in Nevada. The more I heard, the more interested I became in the Patrol, interested and curious. And a journalist afflicted with curiosity has a story on his hands.

It wasn’t until late last summer that I was ushered into the office from which Colonel Jim Lambert runs the Patrol. He is a gray man: grey suit, grey tie, grey hair, grey eyes that aimed themselves steadily at me like gun barrels. He watched me through them coolly as I explained that I wanted to write a story about the Nevada Highway Patrol that would let people know just who that guy is driving the blue and silver patrol car. I wanted to watch the patrolmen at work, I told him, talk to them and find out what their job amounted to, how they handled it, and why they take it on. I wanted to find out where their problems lie and where their satisfactions come from.

As I talked, Lambert sat still, watching me. He looks so much like a policeman you’d think he’d been bred for it: big and burly, like a harness bull; so big in fact, that when he walks his thighs fill up his pant legs tight and the crease disappears. When I finished talking he had apparently decided to pretend that I didn’t look like a stone freak who just might be guilty of half a dozen felonies if he could run his big hands over my pockets, and he agreed to help me get the story.

Lambert himself is a big part of the story. He was born in Idaho, though his family had been living at Dead Horse Wells, near Rawhide, in the 1870s. He came to Reno as a boy and went to school there. He served in the Navy during the World War II and had been a Deputy Sheriff in Washoe County before he joined patrol in 1955, the first man to be hired under uniform civil service codes. Before 1955 patrolmen were appointed, and needed political sponsorship to get the job. Law enforcement on the local level was the only law enforcement Nevada ever really had until the Patrol began to emerge as an effective, coordinated statewide agency in the 1960s, a process that is still surprisingly incomplete.

Lambert has held every job there is in the Patrol, and several that don’t exist within it any longer because the Patrol has been shifted from the agency to agency, its responsibilities expanded and reduced, before assuming its present size and shape.

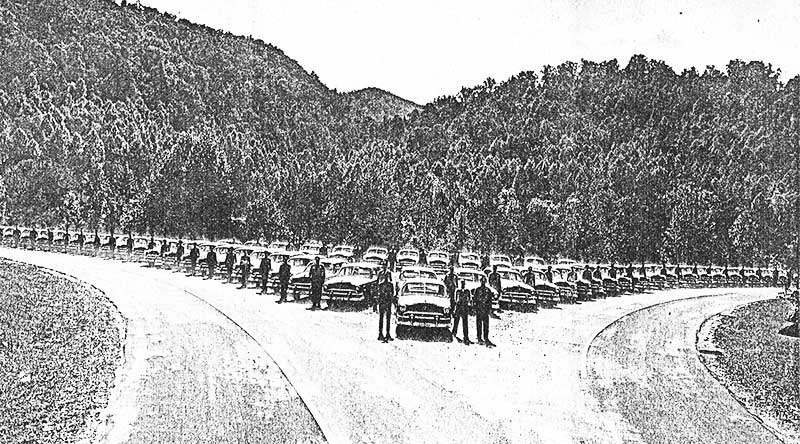

This will surprise you: in California there are about 7,000 uniformed patrolmen of all ranks. Nevada has 121.

These 121 men are assigned to 22 duty stations scattered along the highways that intersect within Nevada’s 110,000 square miles. That is obviously thin coverage, but it is not clear even from these figures just how thin it is.

Consider that about 20 of those 121 men hold headquarters, administrative, training and supervisory jobs. They are not assigned to routine patrol duty except under extraordinary circumstances. Consider too that patrolmen (call them 100 in number for convenience) work a five day week, which means that, like other state employees, each of them has 104 regularly scheduled days off each year. They also get 15 days annual leave and nine holidays. Patrolmen average about 4-1/2 days a year testifying in court, and four days home sick. Each patrolman is also required to spent 14 days every year at in-service training.

You can work it out for yourself: out of the 365 days in the air each patrolman averages 213-1/2 days on patrol duty, 151-1/2 days off patrol duty. That’s a ratio of .585, so the daily average patrol strength is actually 58-1/2 men. Divide that by three; there are three shifts in every 24 hour day though the patrol does not actually run three equal shifts — in fact there is virtually no-one patrolling on the graveyard shift except on Interstates, and then only near Reno and Las Vegas except when traffic peaks during the summer months. What is left is an average of less than than 20 men patrolling Nevada’s highways at any given moment of any given day.

That works out to about one patrolman for each 350 miles of paved highway in the state, or, to put it another way, 40% of the manpower deemed adequate to cope with the level of traffic recorded in 1968. That means, among other things, that there are many places on Nevada’s highways where the nearest patrolman may be two or three hours of fast driving away. Get into an accident out there and you’d better hope you bleed very, very slowly, or all at once.

A few years ago a man and his wife were driving in a pickup truck on Highway 30, a two lane road that takes off north from I-80 in far eastern Elko county to pass through Montello before crossing over the Utah line. It’s about 20 miles from the freeway to Montello, and in that stretch of road, as they sped along, a cow ambled out onto the pavement in front of them. The man swerved, the truck went out of control on the icy pavement and rolled over in the sagebrush before plunging down a ten-foot bank.

The man was killed outright, but his wife was still alive and she somehow managed to struggle out of the wrecked truck, clamber up the steep bank, and crawl to the edge of the road. The temperature was well below freezing, and the woman’s ankle was broken. She could see the lights of Montello clearly, five miles away. She waited there a while, hoping for a car to pass, and then began to crawl. Each little effort cost her pain and blood — she was a stout woman, and not young — but she persisted in her grotesque progress until sometime, they figure, just before dawn. The first car to use the road in the morning found her a little after 7 o’clock, a dead fat woman lying on the center line with her clothing worn away at the knees and elbows and a 4-1/2 mile trail of blood behind her.

The patrolman who told me that horror story told it with an attitude of wonder at the woman’s strength and determination. But there was dejection in his voice too. Not at the ghastly circumstances of her ordeal so much; he has seen as bad and worse many times on the highway. But he was dejected because her death was a defeat for him, just as every highway death is a defeat for the patrolman who could not prevent it.

In his office, Colonel Lambert spelled out the highway patrol’s mission as moving the greatest possible volume of traffic safely over Nevada’s highways. But out on the highway the patrolmen I talked with put it a little differently: above all they are out there to cheat death.

To stave off death a patrolman is prepared to ease your damaged body out of your crushed and crumpled automobile and stop your bleeding until an ambulance can get there, or to cuff your hands behind your back and haul you off to jail. It is not at all accurate to say that it is all the same to him whether he applies handcuffs or a tourniquet, but the patrolmen I met were prepared to do whatever the situation calls for. They realize they are too few to cover every potential for disaster along every road in Nevada. They know they have to play the percentages and concentrate along the major routes of traffic. But they hate it when the percentages give out — when someone dies.

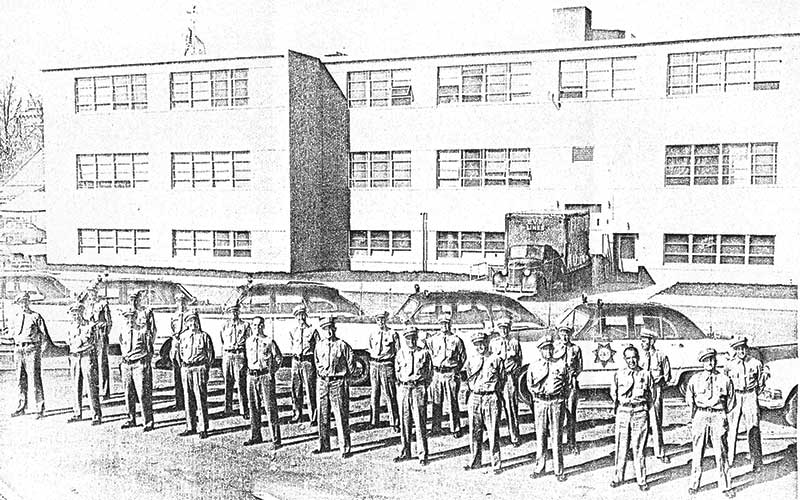

There is general agreement that the essential requirement for a good highway patrolman is a love for people and a powerful drive to be of service to them. Everyone I talked with listed that as the first requirement. Major Cassingham, a crusty old cob who holds down an office job in Carson City, told me that when he first joined the patrol in 1953 total strength was 28 men, who operated two Ports of Entry 24 hours a day in addition to patrolling the highways. He was assigned to Tonopah; there was another patrolman 104 miles northwest at Hawthorne, one 205 miles north at Battle Mountain, one 167 miles east at Ely and four or five 207 miles southeast at Las Vegas.

Under those circumstances he couldn’t bring himself to take a day off very often. He knew someone would need help in his district, and if he was off fishing there’d be no-one to provide it. So he’d hang around the house and wait for the phone to ring, or drive downtown and visit around, but always with his belt and badge in the car. if there was an emergency call for a patrolman, the Sheriff’s dispatcher would give two blasts on the civil defense siren. Levi’s and T-shirt, gun belt and badge, and off he’d go. He got called out so often on his time off that jeans and a T-shirt came to be called the Tonopah uniform.

After an essential compassion for people comes a cluster of other requirements for a good patrolman. One of the most important is that he has his act pretty well together. The Patrol resembles a crack military outfit with its stern standards, rigorous training, and a strong esprit de corps. But the Patrol does not set out to make a man of anyone. There’s no time for that. A good patrolman has to be able to call his shots right from the beginning; make the wrong decision and someone may die because of it. And that will be your death, the one you could have prevented.

You’re on patrol and get an accident call. You race toward it, but it’s a twenty minute drive to where two cars have spun off the pavement into the desert, and one of them is lying on its side with the passengers still trapped inside. There’s a hysterical woman sitting in the other. You know the first thing to do is to prevent the accident from getting worse, so you run down the road setting flares, hoping people are not seriously hurt inside the car.

And there’s a hysterical woman from the other car hobbling and staggering along beside you in her high heels, weeping and screeching, “Shall I call the police, shall I call the police?” It’s night, and you’ve got to see where you’re going by the headlights of the cars that are starting to bunch up as they come around the bend in the road, and you’re going to have a bottleneck on your hands if you don’t get those flares out farther, and there’s no-one within 40 miles to help.

And the people are still inside that car! So you get the flares out, and you take the woman by the arm and snarl at her to get back inside her car and stay there until you tell her to come out, and she is goggling blankly at you, screaming “Call the police! Call the police!” and beginning to faint. And those people have been in the car for more than half an hour already — it’s easy to see how the wrong man could blow that assignment.

“We’ve had men of undeniable courage simply turn in their badges after three weeks on patrol duty,” Colonel Lambert told me. “They could handle the danger, but they couldn’t stand the tension.”

A patrolman put it another way: “Everyone you meet on this job is either sick, hurt, or sore as hell. We are there to help people, but it’s not always easy to keep your attitude good. You go a long time between compliments in this work, and the rewards you do get from people you remember a long time. I remember one accident, people dead and dying all over the highway, and working for what seemed like hours to get them patched together and into ambulances. An old buckaroo came over to me after the last ambulance left, and he took me by the hand. ‘Thank God for people like you,’ he said, and I guess I’ve been working off that little ‘thank you’ for about three years now.”

Patrolman Oster told me at the Patrol Academy that bystanders are a big problem at an accident scene. “They’re trying to help,” he said. “But they don’t know what help you need or how to provide it. You’ll be trying to deal with a badly hurt driver, getting him pinned together and calmed down while we wait for the ambulance, keeping everything cool, keeping the guy as easy in his mind as you can, and then some bystander will stroll over, look down at him and say,”Oh my God!” and throw up. Right away the guy goes into shock, because now he knows it’s bad.”

Most patrolmen will tell you that a man and his job can’t be timid or shy, has to have a good supply of decisiveness and self-confidence, but none of them mentioned to trait I saw in all the patrolmen I talked with. They are orderly men. They like having a everything in its place. The vehicle code is their chief blueprint, and you won’t go wrong if you think of patrolman as maintenance men. But instead of a ramshackle apartment building with leaky pipes and shingles blowing off the roof, they have a highway infested with flaky drivers. This guy with a headlight out(!), that one with an expired license plate or permit, another one passing on a blind curve. . . . It’s a long list of discrepancies that patrolmen hustle around putting right.

Like this one: two cars are proceeding eastward along I-80 at high speed, side-by-side as one passes the other. Behind them is a highballing semi. Suddenly the two cars veer apart. Each of them leaves the payment pavement on opposite sides of the roadway, throwing up the great clouds of dust which at once drift over the road.

The truck driver brakes, but before he can do more than slow his speeding truck, he is into the dust. And there, directly ahead of him, is one of the cars. It has swerved into the median, traded and in a long, looping skid, and come to rest in the middle of the highway. The truck smacks the car back into the median again, and continues on, out of control. It cuts a ragged arc across the median strip, across the two lanes of westbound Highway, mercifully empty, and bounds through a fence out into the desert. There it jounces down a short incline, tips, and crashes over on its side.

Another truck has overtaken the accident now, having slowed at the first sign of disaster and coming to a stop before the dust has settled. The driver opens his door to jump down — and sees a man lying on the pavement near the median strip. At the same time he sees a car approaching from behind. He turned his spotlight to illuminate the body in the road, and then signals frantically to the oncoming driver with his flashlight.

The oncoming driver sees that something is wrong, but he has not seen the accident. He slows, gazing intently at the truck driver, trying to divine the meaning of the frantically waving light. He pulls far over to the opposite side of the pavement and as he passes the truck, his whole attention still riveted on its driver, he feels a flubbery Jolt as his wheels pass over the body in the road. When the patrolman reaches the scene he finds a half-dozen cars and trucks parked along the side of the road, one man dead and a woman dying.

Passing traffic slows down to rubberneck, and everyone on the scene is excited. The survivors of the wreck are near hysteria and one or more of them may be drunk; at the moment it is difficult to tell. It is now up to the patrolman to bring order to this chaos. This he does by recruiting help from the truck drivers. He sends them down the road with flares toward oncoming traffic; his first concern, even before attending to the injured, is to ensure that the accident doesn’t get worse. Then he determines the extent of the injuries and does what he can to help the injured until the ambulance arrives.

When the injured are attended to and ambulanced away he begins his investigation. In this case the investigation required a full day, about four hours of it on the scene. No cause of the accident was determined, and no citation was issued. The second car and driver were never identified or located.

They do their work with no more hostility or belligerence than a journeyman carpenter feels toward a bent nail he pulls out of his work, and behind that urge to neaten up the highway, and justifying it, is the knowledge that people who drive foolishly or with faulty equipment, kill themselves and others. If you feel you must, go ahead and argue, or sweet-talk, or plead when a patrolman pulls you over. He knows just how much mercy cold steel will show you in an accident. He is satisfied that he’s performing an act of service when he gives you that ticket by the side of the road.

One of the 25 patrolmen selected as new hires came from the Gary Indiana Police Department, and from the minute he got off the plane at the Reno airport he kept staring around him at the bald desert hills and the broad sweeps of brushy lowlands that separate them. He had his nose pressed against the car windows all the way out to Stead, the former Air Force Base north of Reno where the patrol conducts its annual 12-week Academy. He just kept swiveling his head around, gazing out at the horizons. They started to show him to his room, and he had his suitcase out of the trunk of the car, but it never touched the ground. He just started shaking his head and had them take him back to the airport. There he waited until he could get another plane back to Gary Indiana, just sitting and looking out at the pastel mountain ranges so far, far away on the horizon.

They lost another man in the ninth week of the Academy. By then an assignment list had been drawn up so that the men with families could have their wives start house hunting. On Labor Day weekend the cadets were sent to their new station assignments to lend a hand to the men on patrol over the busy weekend and see for themselves some of the situations they’ll be dealing with alone, and to see the places they’ll be spending the next year or two of their lives. One of the men sent to Las Vegas saw enough that weekend to last him forever. When he came back to the Academy he turned in his gear and quit. Everybody felt badly about it, but it was better for him and for the patrol to find out early that it wasn’t what he was cut out to do.

There are three Black men among the cadets; they will be assigned to Reno or Las Vegas. It is an unwritten rule that only whites will be assigned to any rural duty station.

I was visiting the Academy a few days after he had left, arriving at dawn to slip inside the gym where Lieutenant Lunt was calling out the cadences for an endless series of calisthenics and the cadets were squirming on the hardwood floor like a herd of gray worms with stomach trouble. After every half dozen exercises, Lunt led the cadets in three or four laps around the gym. He is a big man and in superb physical condition. In a recent endurance race across the Nevada desert, Lunt finished third to Olympic runner Skip Houck and the National Senior Men’s distance running champion.

He wears his hair in a quarter-inch brush cut and talks with a drawl that must have originated somewhere east and south of Nevada. While I introduced myself, Lunt towered above me raining sweat down on my notebook. “Go on over to the mess hall and have some breakfast,” he told me. “i’ll be there in about 20 minutes — I want to run a couple of miles and grab a quick shower before I eat.” I strolled the cafeteria while Lunt dashed away into the sagebrush. I half expected him to be already waiting for me, showered and scrubbed, as I walked through the door.

Lunt runs the Patrol’s training programs, which comprise both the Academy and the continuing in-service training sessions which are conducted the year around in two week segments. When he was a sergeant in Elko, Lunt once swam the Humboldt River in flood tide to rescue a woman perched precariously on the top of her car following an accident on the roadway above.

I asked him if he’d been frightened. “No,” he said. “I’d driven that stretch of road through Carlin Canyon pretty often, and I thought about what I’d do if a car went into the river there. I’d decided I could swim it. So I wasn’t worried about that, but the woman nearly drowned me. She wouldn’t leave her car top without her purse. I kept calling at her to leave the purse and we’d get it later, when we brought the car out. She wouldn’t budge. So I told her to go ahead and throw the purse, which she did, and I dropped it and had to dive for it. And then I took her to shore. Her husband was inside the car, dead.

The cadets are young. Average age is 27 and an average of three years law enforcement experience. Four of the new patrolmen are already assigned to duty; they had transferred over from the California Patrol and have spent only two weeks at the academy before going out into the field. Of the 21 remaining, two had left, leaving 19. They all reflect the Jack Armstrong image the patrol seeks out: big, strapping, healthy specimens who look as if they’ve never entertained an off-color impulse in their lives. “We don’t permit facial hair or long haircuts in the patrol,” Colonel Lambert had told me. “Not because we are opposed to long hair” — he paused to aim his eyes into mine — “but because we believe they would detract from the authority the Patrolman must radiate. It would cause unnecessary questions in the minds of drivers we deal with, and that interferes with a patrolman’s effectiveness. For the same reason, we wouldn’t allow a patrolman to shave his head or carry an axe in his hand either.”

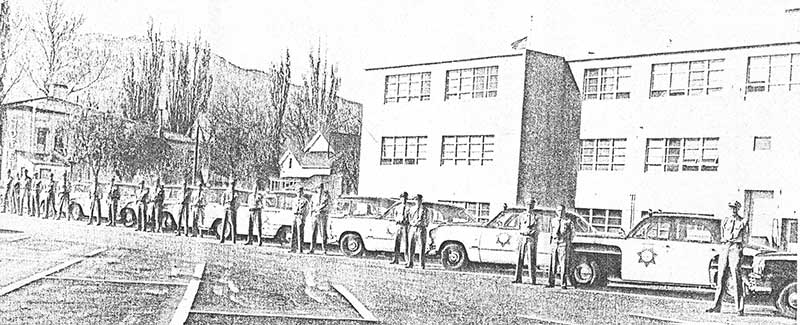

Later in the morning the colonel arrived to talk to the cadets about their weekend performances — a meeting I was firmly ushered out of — and they afterward crowded around him in the coffee room to express their concerns. Lambert explained the Patrol policy, which is to send around a “dream sheet” every year on which a patrolman can list his first, second, and third choices for reassignment. “We are still a small force,” Lambert said, “And that means that we can’t simply sent everybody just where they’d like to be right away. But it’s an unusual thing if a patrolman with five-year service isn’t serving at the duty station of his first choice. The needs of the Patrol come first, and we must assign experienced men to the smaller stations because they’re pretty much on their own out there. As the patrol grows, and we have more experienced people to draw on, the assignment problem gets a little easier every year.”

Lambert tells the cadets that when he was assigned to a new duty station as a patrolman or a sergeant, he cleaned up his own neighborhood first. “If my next-door neighbor broke the law I’d arrest him. I’d him that as long as he stayed legal we’d stay friends, but that I’d bust him all over again if he didn’t. At one new station my first arrest was my own sister-in-law for drunk driving. The word gets around.”

The cadets are gazing at him, not saying much now, wondering just how far down that line they want to go. “It’s for the same reason,” Lambert went on after a pause, “that you can’t go out drinking and whooping it up on your days off with a bunch of friends. Because you’re going to be out on patrol again the next day and may have to arrest them for the very things you were doing with them the night before. You can see why that doesn’t work out.”

There is a rule in the patrol — and this one is written down — that any patrolman caught driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs turns in his badge right then and there and just walks off. No hearing, no appeal, no nothing. He’s through.

The cadets spent nearly 600 hours in class during the twelve weeks of the Academy, but much of the learning takes place in that stainless steel coffee room. From Lambert, from Lunt, from Oster and Gartiez, from the patrolmen who come in to lecture on the various aspects of patrol functions and Nevada law, they learn about the small change of the patrolman’s life. They learn how many patrolmen have to choose between obligations to family and obligations to duty and how they chose. They learn that a small-town assignment can mean living for years in substandard housing, sending their kids to schools run by undernourished school districts, and their wives shopping hundred miles from the supermarket. The patrolman’s life offers few buttresses to a shaky marriage.

The Wells Highway Patrol office is a tiny old silver travel trailer, inherited from the Employment Security Farm Labor Information Office and still wearing its old sign. It is parked out behind one of the cinderblock buildings in the Highway Department maintenance yard and furnished with two tiny desks some filing cabinets and a telephone.

It is from this office that Sergeant Ken Martens normally oversees the activities of the four patrolmen working out of Wells and another two nearly 150 miles south at Ely. But when I visited they’d lost one man by transfer, a new replacement was still in the Academy, another was headed for Reno to testify in court, and a fourth man was due to go on vacation at the end of the week, leaving two patrolmen and Martens to work the 11 “beats” in the Wells District. Those beats off I-80 are patrolled every four or five days, but as shorthanded as it was, Martens was worried that he could not send anyone off the freeway for as long as two weeks.

On patrol with Sergeant Martens between Oasis and Wendover on I-80, heading east. Ahead of us is a newish Ford with Utah plates, clothes hanging from a rack across the back seat. The woman driving pulls out to pass a big U-Haul truck, and she whips around it, barely nipping in as an oncoming car takes to the shoulder to avoid her.

Martens accelerates around the truck, glides up behind her, and hits the toggle switch on the dashboard for the red lights. The woman pulls over and the U-Haul barrels past us as Martens checks in with his dispatcher. He gives the dispatcher his location, describes the car ahead, and reads off its license number. The information is always given in this sequence since if trouble develops the most important thing for the dispatcher to know is where it’s happening. Then a description of the car so in case of trouble the other patrolmen will know what to look for. And finally the license number, since it can be so easily changed if the driver is a fugitive.

Martens is the picture of a Nevada highway patrolman: Young, tall, husky, crisply starched and trimly groomed. He’d been raised on an Idaho farm and been a farmer himself when he was younger. He joined the patrol in 1968, spent 12 weeks at the Academy and was assigned to Las Vegas as a patrolman. Later he was transferred to Motors, the five-man motorcycle squad assigned to patrol duty along the Las Vegas strip and its freeway approaches. He liked the steady shift hours and the 10% pay bonus that went with Motors. But when he became eligible for the sergeant’s exam, he took it.

Some patrolmen never do. One of them explained to me that he loved working the highway, loved working directly with people and wouldn’t be happy behind a desk. Another veteran patrolman I heard about had resisted promotion for years before finally accepting his sergeant’s stripes and a supervisory job in Reno. Four days later he requested demotion back to Patrolman and reassignment back to the small town he just left.

“Everybody joins the Patrol to work the highways,” Martens told me as we headed for Utah on I-80, “But every promotion you get takes you farther and farther away from the work you join to do. You draw more pay but you carry a different set of responsibilities and your satisfactions come in different ways.” But Martens decided to take the sergeant’s exam, and with promotion came the transfer to Wells. He lives with his wife and children in a big blue house trailer parked in an empty patch of gray dirt at the edge of town.

Driving east toward Wendover and the Utah line, Martens told me about an experience Patrolman Bachmeier had a couple of months earlier. He had started to patrol north out of Ely on US 93 one night, and had driven past McGill where the Kennecott smelters process the copper ore mined at Ruth. A few miles beyond McGill there is a small state-maintained Roadside Rest where drivers can pull off the road to sleep. Normally enough for the season Bachmeier saw a car parked in one of the spaces as he passed.

But there was also a suitcase sitting on the pavement by the right front fender of the car, and as Bachmeier drove on that suitcase wouldn’t sit right in his mind. So he drove back into the rest area so that his headlights illuminated the parked car. He could see a man lying with his head lolling against the door on the passenger side of the front seat as he radioed his location to the dispatcher in Elko.

As he replaced his microphone on the dashboard a man rose up in the back seat of the car and sat there a moment, shielding his eyes against the glare of the headlights. Bachmeier asked him to step out of the car, and he did. Bachmeier asked if there were anyone else in the party, and a second man surfaced from the back seat. Backmeier asked him to step out of the car as well.

By this time Bachmeier had been studying the man in the front seat and had seen what looked like blood on his face and neck. He asked the two men about it. “Oh, it’s nothing,” one of them said. “He got a nosebleed earlier. It’s one reason we stopped to rest.” Bachmeier asked him to rouse the man in the front seat and he went over and shook his shoulder, but without response. Bachmeier radioed for a Sheriff’s deputy to come out and then, keeping well clear of the men, he tried to rouse the man himself. As soon as he touched him he knew the man was dead. A postmortem examination determined he had been beaten and strangled to death.

Patrolmen stop every time they see a car at the side of the road. In 1971 the patrol made more than 76,000 highway stops. The issued nearly 29,000 citations and more than 10,000 warnings. They investigated nearly 5,000 accidents and assisted nearly 10,000 motorists with a variety of problems and made nearly 2,500 arrests. They conducted mechanical inspections of well over 13,000 vehicles, recovered 128 stolen cars and set up 24 roadblocks to apprehend fugitives.

A large part of the Academy is devoted to accident investigation. Thousands of dollars may ride on the patrolman’s determination of an accident’s cause, so a patrolman must be shrewd and accurate. From his report citations may be issued, arrests made. To train them in accident investigation, Lunt, Oster and Gartiez arrange cars on one of Stead’s seldom traveled streets to simulate a variety of accidents. They make skid marks on the pavement and park the cars as they “came to rest”. They stop short of bashing out windshields and crumpling fenders — these they indicate by taping bits of paper on which the extent of the damage is written.

Once, when an old Air Force building was being demolished nearby, the instructors spent all morning dragging an old wrecked Oldsmobile up onto the steps and shoving it through the entrance. It looked as if the driver had lost control, smashed into the building, and knocked it down around him. They were pretty pleased with the effect when they dusted off their hands and went to lunch.

But when they brought the cadets over afterward, clipboards and accident report forms in hand, they saw a Reno P.D. patrol car at the curb, red lights flashing, one cop peering into the Olds trying to read the registration slip on the steering column, and another one out searching the sagebrush for the driver. When one of the instructors went over to explain, the Reno policemen weren’t amused and they don’t go to such lengths in staging their accidents at the Academy anymore.

“There are some things we can prepare the cadets to face because we’ve seen them about thousand times and we know they will too. But there’s just no way we can prepare them for the stock truck full of pigs that flips over on the freeway or for that guy, half asleep, who drives his Austin Healey at 100 miles an hour under the back of a semi parked at the side of the road.”

Grim stories are shared in the coffee room. About the deer hunter hurrying home in his VW via Nevada Highway 51 to Carlin, for instance. He was traveling fast and swerved right to avoid a cow in the road, then suddenly left again to avoid her calf. The car flipped, sailed off the highway and down into a deep ditch, its doors accordioned. The driver’s chest was crushed against the steering wheel and he was unable to get out. The car rested in the ditch out of sight all night in freezing temperature, its driver flashing the lights and sounding the horn every time a car went by until the battery finally went dead. Not until 7 am did anyone stop, when they could see his screech-marks leaving the road.

Patrolman Oster told me “At my first accident I drove up to where a crowd of people were standing around the wreck, and one of them looked back over his shoulder at me and said, ‘Thank heavens, here’s the Highway Patrol.’ I actually looked back over my shoulder to see who it was before I realized it was me.”

You and I use Nevada’s highways to reach our destinations; for the Patrolman it is the destination. They drive hundreds miles each shift, but unless they’re answering an accident call they’re not going anywhere. They’re already there. And when I see one, I wave.

Those were the days, my friend! Everyone knew that help was often a long way off, so if you saw someone stopped at the side of the road, you’d pull up and ask if they were OK and did they need anything. People did it for me, long hair hippy that I was.

I am a retired NHP Trooper. I worked with and knew most if not all of the Highway Patrolmen named in this article. I was hired by Jim Lambert in August of 1971, after I returned home from Vietnam. This article is interesting and brings back numerous memories. I respect all of the men I had the opportunity to work with and I thank them for their time and professionalism when we worked the highways of the GREAT STATE OF NEVADA.

Lots of memories here. I remember walking into Lamberts office. He hired me. My academy was number 8 in February of ‘74. Both Lambert and Cassingham were legends on the Patrol. And serving under Governor O’Callahan was a bonus.

I am the youngest son of Lt. Garteiz and in many ways was raised by him and the Nevada Highway Patrol. In reading this article, all the memories and names come flooding back from so many years ago. It is hard to put into words how proud I am of my father and now understand the countless sacrifices he made to be a hero to so many. The NHP brought out all the best in him in so many ways. We miss him every day! A special thanks to all those who made this article possible! Great job by all and thank you for all you do!