Hey, why isn’t Comstock Mining Inc on the map?

It’s not a fair world. You’d think that after spending nearly a quarter of a Billion [uh-huh, billion] Dollars of investors’ money without making a dime in profits and getting some careless Lyon County officials in legal trouble (cost to Lyon County so far: $125,000), that CMI could at least afford to mine something.

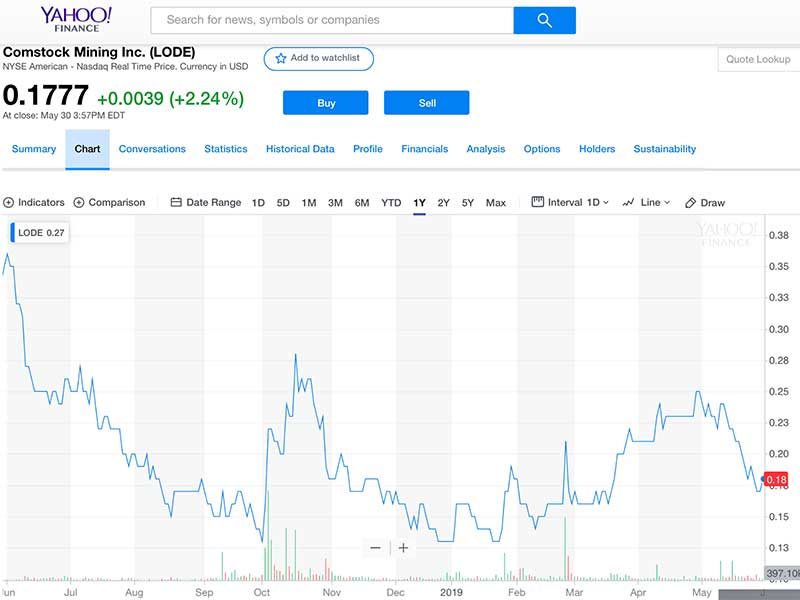

CMI survives despite being the biggest loser in the history of the Comstock Lode (formerly The Richest Place on Earth). The chart shows the performance of CMI stock and reflects the company’s lack of success.

Today’s chart is here. And, while dust gathers on the CMI empire, history marches on.

Lawsuit filed vs. CMI on July 12 2018 by Precious Royalties LLC (“Precious”); CMI stock at 26¢

Precious filed a complaint against CMI for failing “to properly pay” a royalty and seeking $510,000 in damages. Perhaps seeking to postpone judgment until there is some money in the till, CMI waited until November to file a Motion for a “More Definite Statement”. On May 16 the Court granted the Motion, requiring Precious to revise and re-file its complaint.

CMI 3rd Quarter 2018 Losses Reported; at 10/1 CMI stock at 13¢

CMI’s 3rd Quarter 2018 10-Q report to the SEC disclosed income of $32,281 for the quarter, and $83,946 for the year to date, none from mining, all from real estate. Not typos, the absence of zeros is deliberate. The 3-month loss was $2,045,110 and the loss for the year, $6,945,346. Both numbers were modest improvements over the year previous ($2,497,011 and $8,203,913).

On November 27th the ‘mining’ company report about Real Estate sales to the SEC; CMI stock at 16¢

Bill Fain’s Prevenge

Whether it was that awareness that prompted Bill’s decision is probably unknowable now, but when it came time to sell the Gold Hill properties to CMI, he sold the Corporation instead. No title searches were required, since ownership did not transfer out of the corporation. The company then began using Gold Hill Hotel Inc as a holding company, adding other properties over time. Company ownership of the hotel resulted in a loss of local customers, but we were hardly missed. It was an ornament among the company’s holdings, and an investor magnet. Hosting wealthy prospects eventually brought the hotel’s annual operating losses up to a quarter million dollars. Given the much larger losses from the mine, the company couldn’t afford that level of losses and the hotel was leased to a Virginia City restaurant operator. Bill died in 2017 aged 84, respected for the way he’d made the hotel a lively and popular destination. Only now does his hidden legacy reveal itself. A substantial offer for the hotel from a California buyer was in escrow before the title search disclosed the glitch and the sale fell through. A second sale was underway in late 2018 with escrow scheduled to close in December. It was trumpeted as a done deal by De Gasperis and company, but as with the earlier attempt, the sale fell through after a title search. Will CMI ever figure out how to get rid of it? |

“Comstock Mining Inc. (the “Company”) (NYSE American: LODE) announced progress on its non-mining asset sales. The sale of the Gold Hill Hotel, to a local, experienced hotelier remains on schedule for closing in December. The buyer completed the final walk through inspection of the property last week with no material issues noted.”

Storey County Commission meeting, December 4 2018; CMI stock at 16¢

Despite its history in the County CMI was granted a 10-year extension to its Special Use Permit. The Storey County Commission’s generous impulse — previously observed in the $172,000 in discreet goodbye gifts to retiring county employees — were manifested when CMI requested the extension. The Commissioners were not inclined to judge the company’s dismal performance, and no-one from the community wasted the time required to speak in opposition to the gift. In Storey County, citizens who wish to make a public comment — questions are no longer allowed — have to sit for hours before being allowed to speak for a limited amount of time to Commissioners whose interest in listening is minimal at best.

This attitude and the atmosphere it creates has prompted the locals to file law suits as a better way to get the attention of the Commissioners.

As for the local media, the Comstock Chronicle, another gift from Bill Fain to the community, has lately become weak, scrawny and tamer than ever. Fortunately, In recent years we’ve had VC Highlands resident Nicole Barde as an acerbic witness to the Commissioners’ behavior. In February 2017 the Barde Blog was joined by The Storey Teller, published online by Sam Toll from Gold Hill. At last some light is shining into some of Storey County’s darker crevices.

In Lyon County District Court, Monday morning May 13; CMI stock at 23¢

By the time Judge Estes entered his Yerington Court Room, 17 Comstock residents were seated in the pews. The judge was taking a second look, as ordered by the Nevada Supreme Court, at the complaint by Comstock Residents Association et al. that Lyon County and CMI had denied them Due Process by colluding on private phones and email to fix a vote in advance. It didn’t take Judge Estes long to dash whatever by hopes they had that he would see things differently this time.

The judge had found no rule of law that precludes the use of private communications by public servants. And he didn’t think that off-the-record communications between some of the Lyon County Commissioners with officials of CMI showed unacceptable bias leading up to the crucial vote that overturned the Zoning and Master Plan to allow pit mining in Silver City.

The CRA complaint pointed out that two of the Commissioners had received serious money from CMI and should have recused themselves. Judge Estes stated he wouldn’t rethink the Ethics Commission’s decision that absolved the two, and emphasized that they had revealed their financial benefits from the company.

He didn’t think a political contribution of $17,500 made by CMI and two California corporations to then-candidate Hastings was “unreasonably large” for a small county like Lyon, or even particularly unusual, despite its rarity.

Yet with a few exceptions this contribution is almost twice the largest other individual contributions—which are self-funding donations by the candidates themselves. The largest were Ken Gray’s $11,476.60 contribution to his 2016 campaign; Greg Hunewill’s $9,200 contribution to his own 2014 campaign, and John Roemer’s $9,973.09 contribution in the election for the same seat, all far short of the CMI / Winfield total. A typical “large” contribution from any source would be on the order of $2,500. The CMI / Winfield contributions are seven times greater than $2,500.

The business owned by Commissioner Keller and her husband took in $270,000 — more than a quarter million dollars — from CMI and its Comstock Foundation for History and Culture. Even though the Kellers depended on CMI to survive during this period Judge Estes did not believe that Vida’s vote to allow pit mining in Silver City could be blamed on undue influence.

So, taking all in all, Judge Estes again dismissed the CRA complaint.

He instructed Lyon County D.A. to write the opinion, and when it is announced CRA et al. will have 30 days to appeal to the Nevada Supreme Court. That decision isn’t expected to take 30 seconds.

Bottom Line: It’s been more than two years since CMI shares were worth as much as a dollar, longer than that since the company did any mining.

At some time after Bill Fain bought the Gold Hill Hotel and other properties from Fred and Dorothy Immoore in 1982, he transferred ownership to Gold Hill Hotel Inc. without incident. In the years since, it has been revealed that many, most or even all the titles to properties in Gold Hill may not be legally valid because of 19th century oversights.

At some time after Bill Fain bought the Gold Hill Hotel and other properties from Fred and Dorothy Immoore in 1982, he transferred ownership to Gold Hill Hotel Inc. without incident. In the years since, it has been revealed that many, most or even all the titles to properties in Gold Hill may not be legally valid because of 19th century oversights.