by David W. Toll

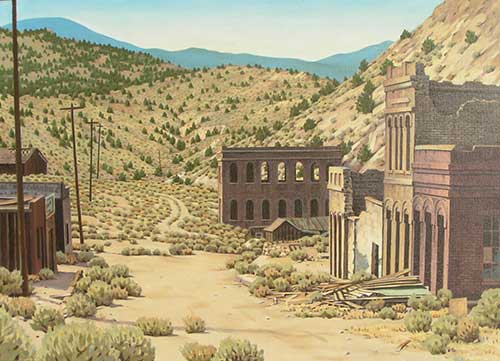

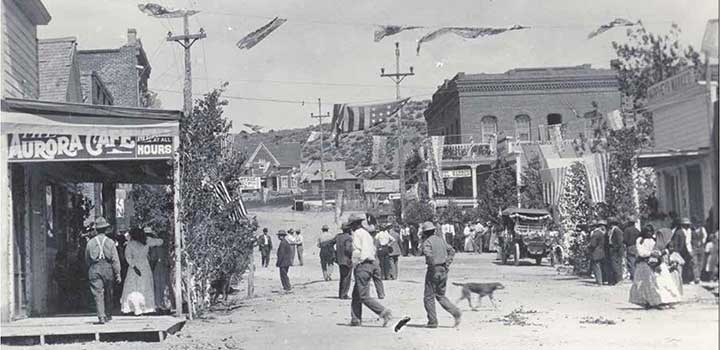

On a sunny summer day in 1946 I walked with my great-grandfather Harry Gorham down Pine Street in Aurora, looking then as you see it in this painting by Jeff Nicholson, and we wandered in the empty city together. He was 88, and I was 10.

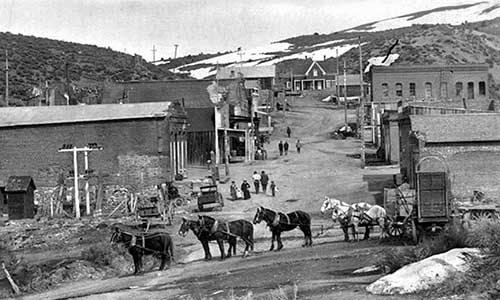

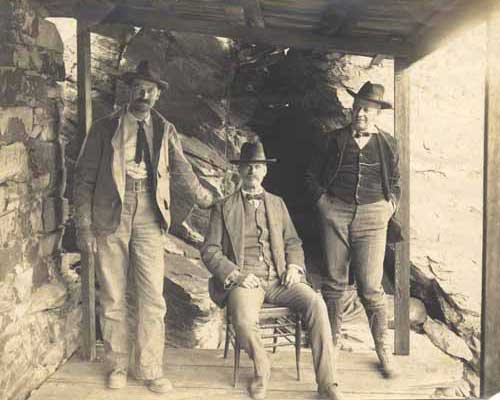

We had traveled to Virginia City, Gold Hill, Lundy, Bodie. Now he was showing me Aurora, a city he and his partners had bought in 1904. Backed by George Wingfield, the great mining millionaire of Goldfield, they had then brought the mines into production again.

The partners laboriously traced property owners who had long since abandoned the old city, he told me, generally offering $10 for a parcel of ground, maybe $20 if it had a building on it. Much of the property had already gone over to the county for non-payment of taxes, and the partners bought some of it at auction.

Altogether, he told me, they paid about $400 for all of the city there was to buy. By that time Aurora’s original boom had been over for 30 years, and only a handful of old men still lived there.

He showed me where their company’s offices had been. He showed me the stage depot where the Franklin and Reo touring cars had pulled in, full of passengers hauled over Lucky Boy Pass from Hawthorne.

He showed me the enormous brick hardware store. They had opened it by sawing off the padlock and swinging the iron fire doors apart, and had found it still fully stocked. In the bins and on the shelves were all the tools, tubs, nuts, bolts, nails, chain, and other items necessary to brace sagging stairways, patch leaky roofs, replace broken windowpanes and otherwise bring an abandoned city into semi-repair. When they brought Aurora back to life for more than another dozen years, the hardware store was a mainstay of the community.

So was the bar room at the Esmeralda Hotel. They had popped its front doors open to find whisky on the shelves and barrels of wine and brandy in the basement. The wine had turned to vinegar, he said, but the brandy was still good and they had called an impromptu party to celebrate the discovery.

Now, 40 years afterward, we peered through the window into the gloomy old barroom, empty again — but with no brandy in the basement this time. He told me of the mines beginning to produce again, and how they had reopened the saloon. He had often stood there at the bar, he said, pointing through the grimy window. I could dimly see chairs shoved back from the dusty poker table in the back. A gambling man had leased that table from the house and dealt poker there. One night when Harry Gorham was standing there, at the bar near the door, the card game was being dealt as usual, with some of the young fellows from the mine sitting in.

Suddenly one of the young miners jumped up from the table. “Double dealing!” he shouted. The gambler sat quietly with his hands on the sawed-off shotgun in his lap.

“I heard the commotion and looked over at the card table,” my great-grandfather told me as we squinted through the window.

“I saw the shotgun come up. All I could think to do was drop to the floor and crawl around behind the bar. I was still on my way down when it went off. Most of the shot hit him in the chest, but some of them missed the man and went the length of the room and right out this front door, which was standing open. One of them hit a burro walking by outside, and sent it screaming and kicking down the street. Some others,” he said, extending his hand and pointing at the top of the door frame, “made these marks.”

I can still see his age-mottled hand pointing at the weathered wood, and the little dents made by the pellets clearly visible.

The young miner was killed. The gambler jumped up and ran out the back door, leaving the saloon filled with smoke, shock and confusion.

“And when the undertaker’s hearse clattered out to the burying ground the next morning,” my great-grandfather said, “it passed beneath the gambler’s body, which was dangling by a rope from the cemetery gate, left there by the young miner’s friends, who had tracked him down and killed him.”

I remember the awe I felt, listening to the old man’s voice in the empty brick city on that bright summer afternoon.

The revival held until 1919. Then the old city began emptying out again. By the time we came to see it together in May, 1946, it was guarded by an old Italian man with a Model A Ford, a dog and a shotgun who got a little grubstake in return for running off vandals and thieves.

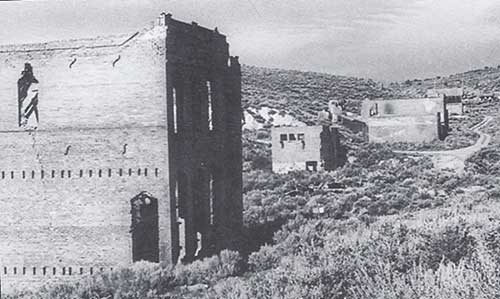

Three months later, in August, all of Aurora’s brick buildings were demolished by a materials-hungry building contractor from Southern California, and hauled away on trucks. The ancient buildings are now factory chimneys in San Pedro and Wilmington — if they haven’t been knocked down and carried off again. The remaining wooden structures, unprotected now, were pulled down by vandals, gravestones were stolen from the cemetery until only a few scraps and sticks remained of this bold city in the wilderness.

More recently a modern mining company built a conglomeration of metal buildings, leach pads, catch ponds and other eyesores where the old city once stood. Other than what’s left of the cemetery, a few photographs, and the memories of the few hundred people still living who actually laid eyes on it, Aurora is gone.

Except for the fascinating chapter it recorded in Nevada history, it might never have existed at all.

A fine story of a great-grandfather who took the time to show his grandson a part of the past which no longer exists. Great pictures of the town and hard to imagine how a community can be here one day and then gone. Regarding Nevada history, I especially like the stories of these “start-up” mining towns, who the people were, where they were from and what were they expecting. A pretty adventurous lot!