If I hadn’t slowed to look down the road west, I probably wouldn’t have noticed the eight-year-old Chevy parked on the shoulder about 100 yards down from the intersection. The hood of the car was up and so was the trunk lid, with the owner rummaging inside. For as far as I could see in any direction, we were the only things moving in the valley.

The hood of the car was up and so was the trunk lid, with the owner rummaging inside. For as far as I could see in any direction, we were the only things moving in the valley.

Three minutes later I was accelerating towards Tonopah with Joe Brown in the seat beside me. A tanned, muscular man of about 40 with close cropped black hair and amber eyes. He wore a light-colored western shirt with mother-of-pearl snaps and a pair of clean, faded JC Penney jeans. Before his car had broken down, he’d been headed into town, from the Linkletter Ranch at Lida, to pick up a new saddle that had been delivered during the week by Greyhound.

As I drove to the ghost city of Goldfield, Joe began to talk a little about the cowboy life in his curiously high-pitched voice. “The horses are poor, the wages are small, and the chuck is bad, but the worst thing is that the ranches aren’t being run anymore the way us cowboys learn to work them. Too many of them set the men to haying and operating machinery. The cow puncher don’t want to build fence and he sure don’t want to drive a tractor. I never cared to be anything but a cowpuncher.”

“A Cowboy’s as dedicated as a priest,” Joe said. “He has to be because you’d be a damn fool to do what he has to do for the money. He has to have a thousand dollars’ worth of tack before he can even get a job that only draws maybe $250 a month. But it’s his judgment that’s responsible for life and death decisions over a $100,000 herd. All I ask for is a bed to sleep in and something to throw my saddle over. But if a saddle won’t fit over it, I sure don’t want it.”

He wasn’t complaining and he wasn’t condemning, but the tradition he’d been raised in was being squeezed out and he knew it. He seemed profoundly disappointed the way a deer is disappointed to find a fence strung up across her way to water.

At Tonopah, Joe checked with the desk clerk at the Mizpah to make sure his saddle was safe, and we walked across the quiet, sunny street to a gloomy cave called the Ace Club. Mounted deer heads spread great racks of antlers out from the walls in a tired display of dusty elegance above us. They seemed to be listening as we talked.

At Tonopah, Joe checked with the desk clerk at the Mizpah to make sure his saddle was safe, and we walked across the quiet, sunny street to a gloomy cave called the Ace Club. Mounted deer heads spread great racks of antlers out from the walls in a tired display of dusty elegance above us. They seemed to be listening as we talked.

Joe was born and raised at Nogales Arizona. As a young lieutenant in the Marine Corps he taught cold weather survival, animal packing and mountain climbing in a small base on east side of the Sierra Nevada. After leaving the Corps, Joe leased a ranch in Arizona with his stepfather. Joe went down to Mexico to buy stock and things were going along pretty well, but in the summer of 1959, he bought a small herd of pony-sized Appaloosa mustangs and went broke when they were quarantined for 90 days at Mexicali.

He cowboyed a year in the Imperial Valley, spent three months breaking wild horses in Phoenix, and then took the few dollars he had saved into the Sierra Madre of northern Mexico to buy 500 head of longhorn cattle for rodeo stock.

“I came away from that cattle deal with $500,” Joe reminisced, “and in the course of getting those animals together two or three head here, half a dozen more there, I’d come to know the country a little and I liked it. So, I bought a little place near Navajoa and I stayed. My main business was buying the mountain Longhorns for rodeo stock in the US, but I ran a few head of my own too. In seven years, I ran my $500 dollars up to $55,000.”

“And then I got greedy. I got hooked up with some big shot American promoters who wanted to buy up 6,000 head in three months’ time and make some big money. When you’re buying them two or three at a time that’s not easy. On top of everything else it turned out I was bankrolling the deal. That’s not the way it was set up, but that’s what happened. So, I got screwed just like I deserved. They got the cattle and I was $22,000 in debt.”

“I don’t regret losing the money, but I sure do miss the life there. I had a neighbor, Don Felipe Sayas, who’d started out as a hide peddler. He was the one who convinced me to stay in the first place, and he took my IOUs until I could get bank credit. He had a big herd by then, so big he never bothered to count it. That way, he said, no one had to know how much money it was worth – not his banker, his bookkeeper, not even himself. He’d look up into the mountains from his porch and wave his arms to take it all in. ‘That’s my bank,’ he’d say. I’ve managed to hang on to that little place near Navajoa. As soon as my kids are educated that’s where I’m headed again.”

“By the time I paid off the debt I didn’t have any cash and I had to find something to do to take care of the kids. I’d been a fair amateur boxer, a light heavyweight champion at Notre Dame, Golden Gloves Champion, and Armed Forces Far East light heavyweight champion. I never fought professional because my hands are small, but I figured then that the time had come to give it a try. So, I went into Navajoa to get myself some prizefights.”

“I won the first 21 straight. In my twenty-second I came up against a young guy named Ramon ‘Buffalo’ Hernandez and he beat my head in. He’s been fighting over on the West Coast since then, he’s no great shakes. But he damn sure whipped me and I figured if he could do it, I’d better quit, and I did. Besides, I’d broken my right hand in the second round. That made the 17th time I’d broken it fighting, and it was getting to where it jingles when I walked. I still haven’t got any grip in it.”

“Well, I wasn’t much ahead from prize fighting, so after that I tried smuggling whiskey. Me and my partner were getting along pretty good until we decided to expand a little. We started smuggling women’s dresses, just $4 and $6 dollar dresses off the rack. He’d go in and buy ’em up at some little store near the border and stuff them into his plane. I was in some backcountry field clearing brush so he could land. Then I’d pack ’em on mules and head for town. Candy bars too. You’d be surprised how much money you can make smuggling Hershey bars into Mexico, especially around Christmas time.”

“But it was hard work and we weren’t making what you call big money because we couldn’t handle very much at a time, so I got greedy again. I paid $750 for $1000 worth of gold to sell in the world market and got stung by a sharp-shooting Mexican conman. I was lucky to come away with $200 cash.”

“That was enough for me. I came out to work for wages. I packed for a year for a Forest Service contractor, building trails up around Duchesne Utah. Then I worked for a summer packing for dudes at Mirror Lake and went down into Mexico selling dairy cattle that winter. The next summer I had enough money to build a small diving outfit and I prospected for placer gold in the streams up in the Sierra Madre. I found some pretty rich pockets but too deep for my little Hollywood rig. Maybe I’ll get back there next summer with a bigger rig.”

I said something to Joe about his adventures making a whale of a book and he looked at me for a moment and nodded. “When I was in Mexico, I wrote all the time. Short stories. I sent them a few places, but nobody wanted them. Then last winter I just stayed home and wrote a novel. “Me Toward the Mexican Sea” I called it, from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Dial Press is supposed to publish it this year. It took me the better part of a year to write, and we were broke again when I was done, so when Gene Adams, we had cowboyed together a little while down in Jalisco, when he called to ask me if I wanted to work for Art Linkletter gathering the wild bovine I said ‘Sure’.”

Joe paused. He looked restless. “Let’s go over to the Mizpah and shoot a little dice.”

We went. There we met John Smith, a small man with a big smile from central Texas who was working on the ranch breaking colts. John rode Tar Baby to win the San Joaquin Quarter Horse Futurity at the Bakersfield Bush Meet, and he was a pretty fair jockey. The three of us drank a little liquor, shot a little dice, played a little 21. My memories of that night on the town are little hazy. Tonopah is an amiable place.

It was after midnight when the 21-dealer scooped up my last dollar. We moved into the coffee shop for a last long lingering cup of coffee before I headed home. “It’s nights like this that I missed in Mexico the most I think,” Joe said. “I like to shoot a little dice and drink a little whiskey, but down there it’s different. You can go into a little Cantina with the men in from their work with a little something to spend and maybe nothing else in the world except that money in their pocket. Their clothes are old, patched, stained a little with their sweat. Now, to our way of thinking these people don’t amount to much. But I can’t count the times I’ve seen one of them step back from the bar and shout out ‘Viva Mexico!’ You don’t have that here.”

As I left, John and Joe were talking about roping deer. “I came on one, one time,” John was saying, “and I got the jump on and just right to where I could drop a loop over him. When he hit the end of that rope, he just bounced right back at me slicing his antlers like a windmill! Spooked my horse something unbelievable! Spooked me too!”

Joe was leaning back, absently stirring his coffee with his ruined right hand and grinning as he listened, his amber eyes shining.

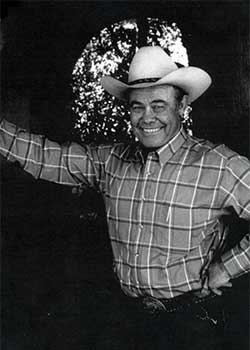

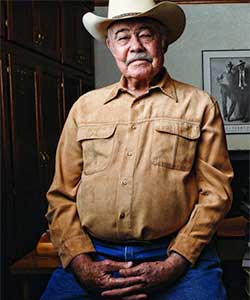

Here’s Joe Brown. In the years following this little adventure he published many books — although none was titled “Me Toward the Mexican Sea” — and became a prominent Arizona author. His novel “Jim Kane” was made into the movie “Pocket Change” starring Paul Newman and Lee Marvin.

Here’s Joe Brown. In the years following this little adventure he published many books — although none was titled “Me Toward the Mexican Sea” — and became a prominent Arizona author. His novel “Jim Kane” was made into the movie “Pocket Change” starring Paul Newman and Lee Marvin.

Here are three relatively recent interviews that reflect Joe’s accomplishments in the years after he left the Linkletter Ranch at Lida:

Here are three relatively recent interviews that reflect Joe’s accomplishments in the years after he left the Linkletter Ranch at Lida:

First, from the Tucson Weekly by Leo Banks in 2007, a visit in which Joe remembered every detail of dying after a heart attack and entering the afterlife.

Five years afer that, Richard Grant interviewed Joe for Cowboys & Indians Magazine.

And five years after that Leo Banks interviewed Joe again, this time for True West Magazine.

What a great story. Thank you.