Nevada’s mountains are like sleeping women, sprawled languorously across every horizon. Peasant women: only a few of them are beautiful or elegant in the usual sense. Most have been scuffed and heaved about too much and their skirts stained with the dried mud of long-vanished inland seas. Even the primitive chic of a forested crest is denied to all but a few of them; the rest make do with threadbare patchworks of scraggy junipers and potbellied pinyon pines draped across their rounded summits. And yet the serene, infinitely feminine presence of these rumpled ranges is mysteriously compelling: their smooth, slumberous forms shade to blue, to purple, to window-glass grey as they recede, rank upon rank, into the distances.

And not merely spatial distance, but vast distances through time as well.

And not merely spatial distance, but vast distances through time as well.

A billion years ago western Nevada was submerged beneath a narrow arm of the sea that had advanced from the south at a time beyond imagining. In four hundred million years this sea had spread to inundate most of the eastern part of the state as well, and had begun to accumulate sand, gravel and mud eroded down from the ancient mountain ranges to the east. Over a period of millions of years the center of the sea’s floor was built up to a thickness of two miles. Limey materials trickled into the sea along its eastern shores where the water was shallow and teeming with life: shellfish, coral, sponges, primitive fish and other worldly plants. These living things also contributed their bodies to the ocean floor.

In the west and north the sea was deeper, and dotted with islands. Most of the islands were volcanic, built up from the ocean floor during thousands of eruptions, hurling flowing projectiles of red hot rock, drooling taffy-stiff, crackling lava and coughing up enormous quantities of ash and smoke. As the achingly, slow, steady process of deposition was ending in the oceans covering Nevada, the eastern seaboard of North America was lifting up out of the ocean.

In the west and north the sea was deeper, and dotted with islands. Most of the islands were volcanic, built up from the ocean floor during thousands of eruptions, hurling flowing projectiles of red hot rock, drooling taffy-stiff, crackling lava and coughing up enormous quantities of ash and smoke. As the achingly, slow, steady process of deposition was ending in the oceans covering Nevada, the eastern seaboard of North America was lifting up out of the ocean.

Then, some 350 million years ago, at about the same time the first sharks appeared in the seas, the process of uplift began in Nevada. The sea floor began to bulge upward along a line extending through the approximate center of the state along a northeast-southwest axis. As this long, narrow belt of land emerged from the depths of the sea, erosion began to nibble at it immediately, washing the exposed sea-bottom back into the sea again. As this was taking place, immense stresses from deep within the earth combined to shove the upper layers of the earth’s crust many miles eastward. Erosion continued, and the mountains were nibbled to nothing. Some 275 million years ago, at the approximate moment of the appearance of ancestral pines on its dwindling shores, the sucking, lapping sea closed over the exposed land again.

Then, some 350 million years ago, at about the same time the first sharks appeared in the seas, the process of uplift began in Nevada. The sea floor began to bulge upward along a line extending through the approximate center of the state along a northeast-southwest axis. As this long, narrow belt of land emerged from the depths of the sea, erosion began to nibble at it immediately, washing the exposed sea-bottom back into the sea again. As this was taking place, immense stresses from deep within the earth combined to shove the upper layers of the earth’s crust many miles eastward. Erosion continued, and the mountains were nibbled to nothing. Some 275 million years ago, at the approximate moment of the appearance of ancestral pines on its dwindling shores, the sucking, lapping sea closed over the exposed land again.

After a few tens of millions of years, perhaps twenty, the ocean floor was once again uplifted above the surface of the sea. Reptiles of increasing complexity and specialization quickly dominated the life on the land. Only slowly and occasionally did upward thrusting pressures push mountains above the level of the dominating plain. Sometimes molten rock welled up through cracks and fissures in the crust, this hot mass sometimes escaping to the surface as lava, sometimes cooling and solidifying beneath the surface to become granite. As the new mountains eroded in their turn, their debris built up the plains between them.

After a few tens of millions of years, perhaps twenty, the ocean floor was once again uplifted above the surface of the sea. Reptiles of increasing complexity and specialization quickly dominated the life on the land. Only slowly and occasionally did upward thrusting pressures push mountains above the level of the dominating plain. Sometimes molten rock welled up through cracks and fissures in the crust, this hot mass sometimes escaping to the surface as lava, sometimes cooling and solidifying beneath the surface to become granite. As the new mountains eroded in their turn, their debris built up the plains between them.

Plant life flourished and new species of life appeared. In the seas ichthyosaurs, swimming reptiles the size of whales, dominated for ages. Dinosaurs later ranged the land, birds and small mammals appeared. A broad sea still covered the region we now call the Mid-west, and at its eastern shore the Appalachian Mountains loomed up as tall as the Rocky Mountains are today.

One hundred fifty million years ago a mass of the earth’s crust tilted sharply up along its eastern edge, sloping gently toward the west: the birth of the Sierra Nevada. In the Sierra and elsewhere in Nevada, too, volcanic activity increased in volume and intensity. This intense volcanic period marked the beginning of the present chapter in the geologic evolution of Nevada -the breaking of the earth’s outer crust into huge, north-south elongated blocks.

One hundred fifty million years ago a mass of the earth’s crust tilted sharply up along its eastern edge, sloping gently toward the west: the birth of the Sierra Nevada. In the Sierra and elsewhere in Nevada, too, volcanic activity increased in volume and intensity. This intense volcanic period marked the beginning of the present chapter in the geologic evolution of Nevada -the breaking of the earth’s outer crust into huge, north-south elongated blocks.

Similar parallel cracking occurred over a region extending beyond Nevada into western Utah, southeastern California, western and southern Arizona and southern New Mexico. The mountains heaved up there appeared in a characteristic pattern: long ranges thrust up parallel to the faults, separated from one another by more or less broad flat valleys. This is the Basin and Range Province and it covers virtually all of Nevada. Within this huge province is the Great Basin, extending from the Sierra to Utah and from Idaho down to Arizona, an area out of which there is no drainage to the sea.

Similar parallel cracking occurred over a region extending beyond Nevada into western Utah, southeastern California, western and southern Arizona and southern New Mexico. The mountains heaved up there appeared in a characteristic pattern: long ranges thrust up parallel to the faults, separated from one another by more or less broad flat valleys. This is the Basin and Range Province and it covers virtually all of Nevada. Within this huge province is the Great Basin, extending from the Sierra to Utah and from Idaho down to Arizona, an area out of which there is no drainage to the sea.

These mountains were aging when man first appeared in the world a million years ago, and some ninety-six hundred centuries passed until the first man set eyes on them. By then, even though the ranges were rising (as they still are), their summits were continuing to wear away, and their contours were more rounded. Their bases were fuller, built up above the flat valley floors by the deposition of sediment by erosion. Flash floods had gnawed channels down the hillsides, and brush and trees had taken root long before.

These mountains were aging when man first appeared in the world a million years ago, and some ninety-six hundred centuries passed until the first man set eyes on them. By then, even though the ranges were rising (as they still are), their summits were continuing to wear away, and their contours were more rounded. Their bases were fuller, built up above the flat valley floors by the deposition of sediment by erosion. Flash floods had gnawed channels down the hillsides, and brush and trees had taken root long before.

The first men to see Nevada’s mountains on the horizon about 40,000 years ago were far travelers from Asia, possibly the ancestors of the Indians. Those who did not pass on settled in the valleys between the mountain ranges where food was plentiful enough to sustain their small and mobile populations. They ranged up into the heights to harvest pinon nuts and to hunt deer and elk, but for the most part they had no need to leave the valleys.

The first men to see Nevada’s mountains on the horizon about 40,000 years ago were far travelers from Asia, possibly the ancestors of the Indians. Those who did not pass on settled in the valleys between the mountain ranges where food was plentiful enough to sustain their small and mobile populations. They ranged up into the heights to harvest pinon nuts and to hunt deer and elk, but for the most part they had no need to leave the valleys.

Only 140 years ago, according to recorded history, the first Europeans came within sight of the mountains of Nevada: trappers who pushed south into the state in search of beaver and otter for pelts. They came downstream out of the Idaho high country, pressing as far south as the Humboldt River and its tributaries. Their intrusion was brief, but soon after them came the vanguard of the wave of California-bound immigrants. The wagon trains held to the lowlands, traveling miles out of their way, if necessary, to avoid a mountain crossing. They threaded their way along the banks of the Humboldt, whipped their starving animals across the Forty-Mile Desert to the stone barricade of the Sierra, rested there awhile, and pushed on. For nearly twenty years in the aftermath of the discovery of gold in California wagon trains made the exhausting and dangerous Nevada crossing. They had no love for Nevada’s mountains. Most of men’s activities have always been centered in the basins rather than those forbidding mountains.

Only 140 years ago, according to recorded history, the first Europeans came within sight of the mountains of Nevada: trappers who pushed south into the state in search of beaver and otter for pelts. They came downstream out of the Idaho high country, pressing as far south as the Humboldt River and its tributaries. Their intrusion was brief, but soon after them came the vanguard of the wave of California-bound immigrants. The wagon trains held to the lowlands, traveling miles out of their way, if necessary, to avoid a mountain crossing. They threaded their way along the banks of the Humboldt, whipped their starving animals across the Forty-Mile Desert to the stone barricade of the Sierra, rested there awhile, and pushed on. For nearly twenty years in the aftermath of the discovery of gold in California wagon trains made the exhausting and dangerous Nevada crossing. They had no love for Nevada’s mountains. Most of men’s activities have always been centered in the basins rather than those forbidding mountains.

Inevitably a few travelers stayed behind. Some broke the rich ground at the eastern base of the Sierra and planted crops. Others built shanties and corrals at fruitful places and established trading posts to provision the wagon trains coming after. A few more prospected for the gold they could not find in California.

Inevitably a few travelers stayed behind. Some broke the rich ground at the eastern base of the Sierra and planted crops. Others built shanties and corrals at fruitful places and established trading posts to provision the wagon trains coming after. A few more prospected for the gold they could not find in California.

Some of these last found placer gold in a stream feeding the Carson River and enthusiastically established a mining district headquartered at the slapped-together village of Johntown. They patiently panned the gold, following it farther and farther upstream where their patience was tested by the persistent presence of sticky, blue-black mud that made the recovery of gold increasingly difficult. The freezing winters, the seasonal flow of the creek and the infuriating presence of the “blue stuff” made the going slow. But gold was there and they did not abandon it.

Some of these last found placer gold in a stream feeding the Carson River and enthusiastically established a mining district headquartered at the slapped-together village of Johntown. They patiently panned the gold, following it farther and farther upstream where their patience was tested by the persistent presence of sticky, blue-black mud that made the recovery of gold increasingly difficult. The freezing winters, the seasonal flow of the creek and the infuriating presence of the “blue stuff” made the going slow. But gold was there and they did not abandon it.

It was 1859 before they had followed the stream to its source on the southern flank of the Virginia Range. There the ragtag prospectors from Johntown sank their picks into one of the richest treasure-troves of gold and silver the world had ever seen: the Comstock Lode.

There was nothing in the bald and rounded appearance of the Virginia Range to suggest the immense deposits of precious metals concealed barely beneath its soil; men suddenly awoke to the urgent realization that there was more to Nevada’s mountains than simply the necessity of traveling the long way to get around them. Even before the lode had been wholly claimed, before Virginia City and Gold Hill were more than haphazard hillside gatherings of brush-roofed dugouts and unchinked leantos, prospects were trailing our into the unexplored vastnesses of Nevada, hurried along by the promise of bigger strikes to come. And they found them-big strikes that made fortunes, though seldom enough for the men who uncovered them.

There was nothing in the bald and rounded appearance of the Virginia Range to suggest the immense deposits of precious metals concealed barely beneath its soil; men suddenly awoke to the urgent realization that there was more to Nevada’s mountains than simply the necessity of traveling the long way to get around them. Even before the lode had been wholly claimed, before Virginia City and Gold Hill were more than haphazard hillside gatherings of brush-roofed dugouts and unchinked leantos, prospects were trailing our into the unexplored vastnesses of Nevada, hurried along by the promise of bigger strikes to come. And they found them-big strikes that made fortunes, though seldom enough for the men who uncovered them.

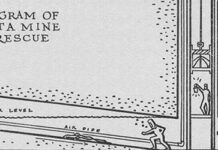

Within a few years after the discovery of the Comstock hordes of miners had swarmed into the mountain ranges of Nevada, working in round-the-clock shifts to dig deeper and plunder them of silver, gold, and other metals. In those glory years bustling wagon roads were gouged in switchbacks to connect the thriving, rawboned mining towns on the mountainsides with the dusty thoroughfares scratched along the lengths of the valleys below.

Within a few years after the discovery of the Comstock hordes of miners had swarmed into the mountain ranges of Nevada, working in round-the-clock shifts to dig deeper and plunder them of silver, gold, and other metals. In those glory years bustling wagon roads were gouged in switchbacks to connect the thriving, rawboned mining towns on the mountainsides with the dusty thoroughfares scratched along the lengths of the valleys below.

The minerals which contributed so profoundly to the settling and development of Nevada were gifts from its mountains, laid away during the volcanic mountain building that began thirty million years ago. Much of it has been found but much more remains hidden still. In 1969 alone Nevada mines accounted for the production of $170,000,000 of raw wealth, and millions of dollars are spent each year in the quest for more of the mineral deposits that run through the ancient rock like fat through a beefsteak.

The minerals which contributed so profoundly to the settling and development of Nevada were gifts from its mountains, laid away during the volcanic mountain building that began thirty million years ago. Much of it has been found but much more remains hidden still. In 1969 alone Nevada mines accounted for the production of $170,000,000 of raw wealth, and millions of dollars are spent each year in the quest for more of the mineral deposits that run through the ancient rock like fat through a beefsteak.

The ranches scattered through Nevada’s lonely valleys depend on the mountains above for water. Spring-fed streams provide some of it, snowmelt provides more. Without it no rancher could run enough cattle during the mid-summer grazing period.

The ranches scattered through Nevada’s lonely valleys depend on the mountains above for water. Spring-fed streams provide some of it, snowmelt provides more. Without it no rancher could run enough cattle during the mid-summer grazing period.

The significance of the mountains to Nevada cannot be over-emphasized. Dramatic evidence of this fact is that they continue to build. In 1915 severe earthquakes and faulting occurred in Pleasant Valley. In 1932 the Gabbs Valley was shaken by massive shifts in the earth’s crust. In 1954 the Dixie Valley was the scene of violent shifting and cracking. It has only been a few thousand years since the most recent volcanic eruptions in Nevada, and there is no evidence to indicate that volcanic activity has ended. The process of mountain building continues. Some of the sleeping women on the horizon are on the verge of waking.

The significance of the mountains to Nevada cannot be over-emphasized. Dramatic evidence of this fact is that they continue to build. In 1915 severe earthquakes and faulting occurred in Pleasant Valley. In 1932 the Gabbs Valley was shaken by massive shifts in the earth’s crust. In 1954 the Dixie Valley was the scene of violent shifting and cracking. It has only been a few thousand years since the most recent volcanic eruptions in Nevada, and there is no evidence to indicate that volcanic activity has ended. The process of mountain building continues. Some of the sleeping women on the horizon are on the verge of waking.

EDITOR’S NOTE – This article was prepared in consultation with John H. Schilling, Nevada Bureau of Mines, University of Nevada, Reno. The original story was published in Nevada Magazine, Spring 1971. Photos by Robin Cobbey.

Wonderful writing. David sure had a way with words.