by Jim Reed

In signing his famous “letter from Carson City” on January 31, 1863, the man directing the pen morphed from Samuel Langhorne Clemens to Mark Twain with just a few wriggles of his wrist. The world of literature had gained an immortal. This was the first known use in writing of the nom de plume “Mark Twain.” The letter was directed to the editors of Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise, Twain’s employer. It is an early example of his devilish wit and skill with the pen.

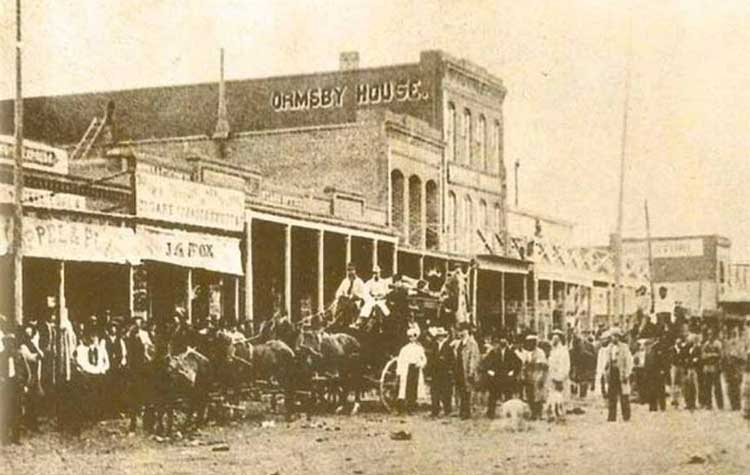

Local legend has it that Twain wrote the letter from the parlor of his brother Orion’s home at the corner of Division and Spear streets in Carson City. He did not. The home was not completed and occupied until the following year. The Enterprise had assigned Twain to cover the Nevada Territorial Legislature, so he could have written the letter from any number of places in town, including one of the bars he frequented with his pals.

Orion Clemens was the Territorial Secretary, having been appointed by Abraham Lincoln in 1861. Although his life has been chronicled by Nevada and Twain historians, the general public—at least those who have heard of Orion Clemens at all—largely know him as the brother of Mark Twain. Yet his accomplishments during the four years he served as Secretary were fundamental to Nevada’s eventual statehood.

Twain’s letter is a sketch about a party he attended at J. Neely Johnson’s home in Carson City. Neely, the fourth governor of California, had moved to the Nevada Territory in 1861 to resuscitate his political career. He became a member of the Nevada Constitutional Convention and was a leader in the run-up to statehood. He later served on the Nevada Supreme Court.

Describing Johnson’s party, Twain says in the letter that after engaging in small talk and dancing a quadrille, “I smelled hot whisky punch, or some thing of that nature. I traced the scent through several rooms, and finally discovered the large bowl from when it emanated. I found the omnipresent Unreliable there, also.” Friend and fellow reporter Clement T. Rice had had the temerity (at least to Twain’s mind) to criticize a Twain report on the doings at a session of the Territorial Legislature. Twain had written in response that Rice’s comments were a “festering mass of misstatements, the author of whom should be properly termed the ‘Unreliable.’” Rice was thus and evermore the Unreliable when he appeared in Twain’s writings.

All in good humor, Rice and Twain slung barbs for years. Once while on his sick-bed Twain asked Rice to sub for him and produce a column for the Enterprise. Rice obliged and wrote a column over Twain’s name headlined “APOLOGETIC.” It begins: “It is said that ‘open confession is good for the soul.’” It asks forgiveness from all those “whom we [Twain] have ridiculed from behind the shelter of our reportorial position,” and promises that in the future we will give them no cause but the best of feelings toward us. It cites Rice in particular, toward whom “we have been as mean as a man could be.” And it promises: “We shall now go in sackcloth and ashes for the next forty days. What more can we do?”

When he read the column attributed to him, it was enough to cure Twain’s sickness. He was far from the meek apologizer Rice made him seem to be, so he retaliated. He wrote in the Enterprise that he was to blame for allowing the Unreliable the opportunity to misrepresent the facts:

“We simply claim the right to deny the truth of every statement made by him in yesterday’s paper, to annul all apologies he coined as coming from us, and to hold him up to public commiseration as a reptile endowed with no more intellect, no more cultivation, no more Christian principle than animates and adorns the sportive jackass rabbit of the Sierras. We have done.”

No surprise then that the Unreliable appears in the letter from Carson City. Twain says that when they met at the whiskey punch bowl, the Unreliable mentioned that he was seeking the gentlemen’s room. Twain says that he’d have shown the way, but it occurred to him that perhaps they should not leave the supper table and the punch-bowl unprotected. And so they stood guard “until the punch entirely evaporated.” It had a predictable effect, for after they left the refreshed punch bowl in charge of a servant and joined the dancing crowd, “the dance was hazier than usual … Everything seemed to buzz, at any rate.”

Supper was served and it gave Twain, now imbued with a buzz, the idea for a few more slings and arrows he would direct toward the Unreliable in his letter:

“I never saw a man eat as much as he did in my life. I have the various items of his supper here in my note-book. First, he ate a plate of sandwiches; then he ate a handsomely iced poundcake; then he gobbled a dish of chicken salad; after which he ate a roast pig; after that, a quantity of blancmange; then he threw in several glasses of punch to fortify his appetite, and finished his monstrous repast with a roast turkey. Dishes of brandy-grapes, and jellies, and such things, and pyramids of fruits, melted away before him as shadows fly at the sun’s approach. I am of the opinion that none of his ancestors were present when the five thousand were miraculously fed in the old Scriptural times. I base my opinion upon the twelve baskets of scraps and the little fishes that remained over after that feast. If the Unreliable himself had been there, the provisions would just about have held out, I think.”

After supper the party-goers devolved to the parlor for music, to be supplied by the guests themselves. Knowing that the recipients of his letter—the staff at the Enterprise—would recognize the party people he is writing about, Twain indulges in some tongue-in-cheek fun. This part of the letter, humorous as it is, gives one a good feel for the way in which the elite in towns in the territory entertained themselves in those days.

He identifies the ladies by the first letters of their last names. For example: “Mrs. J. sang a beautiful Spanish song; Miss R., Miss T., and Miss S., sang a lovely duet.” Four other ladies “sang ‘meet me by the moonlight alone’ charmingly.”

Twain plays music critic and has more fun with the men:

“Horace Smith, Esq., sang ‘I’m sitting on the stile, Mary,’ with a sweetness and tenderness of expression which I have never heard surpassed;

“Col. Musser sang ‘From Greenland’s Icy Mountains’ so fervently that every heart in that assemblage was purified and made better by it;

“Judge Dixon sang ‘O, Charming May’ with great vivacity and artistic effect;

“Joe winters and Hal Clayton sang the Marseilles Hymn in French, and did it well;

“Mr. Wasson sang ‘Call me pet names’ with his usual excellence (Wasson has a cultivated voice, and a refined musical taste, but like Judge Brumfield, he throws so much operatic affectation into his singing that the beauty of his performance is sometimes marred by it – I could not help noticing this fault when Judge Brumfield sang ‘rock me to sleep, mother);

“Wm. M. Gillespie sang ‘Thou has wounded the sprit that loved thee,’ gracefully and beautifully, and wept at the recollection of the circumstance which he was singing about.”

Twain writes that up until this time “I had carefully kept the Unreliable in the background, fearful that, under the circumstances, his insanity would take a musical turn; and my prophetic soul was right.” The unreliable planted himself at the piano, opened his “cavernous mouth,” and “the effect upon that convivial audience was as if the gates of a graveyard, with its crumbling tombstones, had been thrown open in their midst … there was no more sense in it [the Unreliable’s singing], and no more music, than there is in his ordinary conversation. The only thing in the whole wretched performance that redeemed it for a moment, was something about ‘the few lucid moments that dawn on us here.’ That was all right; because the ‘lucid moments’ that dawn on the Unreliable are almighty few, I can tell you.”

As the party waned in the late hours, Twain says that after “the Unreliable had finished squawking, I sat down to the piano and sang – however, what I sang is of no consequence to anybody. It was only a graceful little gem from the horse opera.”

As time would tell however, this was in fact a consequential performance; it was a harbinger of things to come in the career of a man who would become the nation’s best-known writer. Years later he would often sit singing a little gem from a horse opera, seemingly oblivious to the crowd, as the curtain opened on one of his lectures, the whole of which set him on the road to fame.

When he signed the letter from Carson City, America had its Mark Twain, and Tom and Huck and Becky Thatcher and Aunt Polly would come along to loom large in literary lore.