In Nevada, even in our Age of Tesla, it is still possible to venture as deep into history and prehistory as you care to go. Here’s a day trip from Ely or Eureka that will take you off the pavement and into the scenery, out of sight of the modern world.

We’re going to visit Hamilton, once and briefly a thriving city of 10,000 people at 8,000 feet above sea level in the White Pine range, and on the way we are taking in the Belmont Mill and the mine that supplied it with ore when it was a minor wonder of the mining world.

We’re going to visit Hamilton, once and briefly a thriving city of 10,000 people at 8,000 feet above sea level in the White Pine range, and on the way we are taking in the Belmont Mill and the mine that supplied it with ore when it was a minor wonder of the mining world.

To do this, bring the survival essentials: digging implements, jacks and wrenches, fluids, and the 3 Bs: blankets, books and beer.

Then get yourself onto US 50 where the Green Springs Road takes off to the south at the far eastern edge of Newark Valley. If you’re coming from Ely that means driving about 10 miles west of the marked road to Illipah and Hamilton until you see the sign pointing south toward the Belmont Mill and Green Springs. That’s where you turn. Coming from Eureka you’ll see the turn-off just before the road begins its climb to Little Antelope Summit.

It’s a 9-mile drive, with no real rough spots, well-marked and undemanding, and after merging with another dirt road, markers appear announcing that you are now driving on the Lincoln Highway. You are now experiencing highway travel just as your great-grandparents did, only faster and with NPR on the radio.

It’s a 9-mile drive, with no real rough spots, well-marked and undemanding, and after merging with another dirt road, markers appear announcing that you are now driving on the Lincoln Highway. You are now experiencing highway travel just as your great-grandparents did, only faster and with NPR on the radio.

The Great Automobile Race came this way in 1908, with mechanic George Schuster at the wheel of the Thomas Flyer leading the pack from Ely to Tonopah, San Francisco and Paris via Hamilton and Railroad Valley. But we are not in a race, and with stops for photographs we take a half hour to get to the Belmont Mill.

The mill is located near the mouth of McEllen Canyon, between Pogonip Ridge and Mount Hamilton immediately to the west and Babylon Ridge to the east.

The mill is located near the mouth of McEllen Canyon, between Pogonip Ridge and Mount Hamilton immediately to the west and Babylon Ridge to the east.The mill is not named for the community northeast of Tonopah, but for the company that built it in 1926. The Tonopah Belmont Development Company was a major mining company with properties in Tonopah and Goldfield, which by then were in decline. The mill was built using parts and machinery scavenged from the company’s operations there.

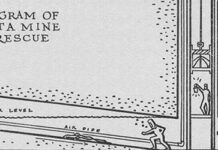

The structure is a rare survivor from those earlier times, relatively intact with the major exception of the Power House that stood next to it with a huge diesel engine inside. This supplied the motive power that turned the wheels to activate the gyres, the gimbals, the aerial tramway with buckets dangling, the paddles in the big cyanide tanks turned by belts, even the electric light bulbs overhead.

The engine turned a shaft that extended from the powerhouse into the mill itself and turned the gears that kept the aerial tramway reliably delivering ore from the mine, one bucketful at a time, no matter what the weather.

When we visited on this beautiful autumn day, the place was deserted at midmorning. We’d seen no-one on the road coming in, and there was no-one here either. There was no sound except the sounds of the earth, and no notion of the wider world. In fact, the only sign of an active presence is the evident amount of recent work that has been invested by the federal government. Less effort seems to have been made to preserve lesser structures, and some of them are losing their shapes as they merge down into the earth.

When we visited on this beautiful autumn day, the place was deserted at midmorning. We’d seen no-one on the road coming in, and there was no-one here either. There was no sound except the sounds of the earth, and no notion of the wider world. In fact, the only sign of an active presence is the evident amount of recent work that has been invested by the federal government. Less effort seems to have been made to preserve lesser structures, and some of them are losing their shapes as they merge down into the earth.

We wandered freely through the old structures, marveling over them. We made note of the stout concrete footings and new timbers thoroughly braced, and studied the mechanism that pulled the cable down, emptied the buckets, and sent it back three miles up the mountain for more.

We wandered freely through the old structures, marveling over them. We made note of the stout concrete footings and new timbers thoroughly braced, and studied the mechanism that pulled the cable down, emptied the buckets, and sent it back three miles up the mountain for more.

We prowled around separately, figuring things out as we went. Mercifully, there are no informational plaques to interfere with the experience.

After a while we had lunch underneath the great tree that provides shade on hot days, and then we drove to the mine at the other end of the tramway. This requires backtracking to the first intersection and turning right, onto the road the climbs higher and higher up the mountain. And higher and higher.

After a while we had lunch underneath the great tree that provides shade on hot days, and then we drove to the mine at the other end of the tramway. This requires backtracking to the first intersection and turning right, onto the road the climbs higher and higher up the mountain. And higher and higher.

It’s a good road, but near the top there is a narrow squeeze between the steep cliff on one side and the abyss on the other. It’s quite passable but somewhat discombobulating if you are susceptible to altitudinal-disparity discombobulation.

Whatever unease you feel on the way up is rewarded by the opportunity to explore the mine undisturbed. It is so high up on this remote mountainside that it seems utterly unlikely to have been found. Who was climbing around up here, looking for silver in 1867? Enough of them to have established the White Pine Mining District a couple of years before.

Whatever unease you feel on the way up is rewarded by the opportunity to explore the mine undisturbed. It is so high up on this remote mountainside that it seems utterly unlikely to have been found. Who was climbing around up here, looking for silver in 1867? Enough of them to have established the White Pine Mining District a couple of years before.

Here we explored the upper terminus of the tramway and followed the trail of the ore from the portal of the mine down to the structure where the cable was pulled around and sent back down again with its buckets full. Their extra weight minimized the amount of energy needed to operate the system.

Once again we were grateful for the lack of helpful information on the site. This is not an exhibit, not a pinned butterfly, not a pressed flower, it is a real thing, seemingly abandoned, and we have just discovered it. Don’t burden us with factoids, we are exploring it for ourselves, and having fun doing it. It’s not a teachable moment anyway, it’s an exaltable moment.

Once again we were grateful for the lack of helpful information on the site. This is not an exhibit, not a pinned butterfly, not a pressed flower, it is a real thing, seemingly abandoned, and we have just discovered it. Don’t burden us with factoids, we are exploring it for ourselves, and having fun doing it. It’s not a teachable moment anyway, it’s an exaltable moment.

We clambered around snapping photos, marveling over our discoveries and wondering out loud. By the time we headed back down the mountain we had thoroughly devoured and digested the place without knowing a single thing about it.

From here we retraced our route down the steep side of the Pogonip Ridge, and continued past the road to the mill to the next junction and made a right turn. Now we are back on the Lincoln Highway again, making for Hamilton just three miles away at 30 mph and filled with anticipation. What a beautiful day!

From here we retraced our route down the steep side of the Pogonip Ridge, and continued past the road to the mill to the next junction and made a right turn. Now we are back on the Lincoln Highway again, making for Hamilton just three miles away at 30 mph and filled with anticipation. What a beautiful day!

In 1867 one of the miners exploring the White Pine District was given a heavy piece of silver chloride by a local Indian in return for a purloined pot of beans (as the story goes). He and some pals located the ground it came from and began working it. The find was high on what quickly became known as Treasure Hill, and as others heard about it, they joined the search for more. By the time the first snow fell, a rough little city had built up among the mines of the local rock in plentiful supply, and lumber freighted in from afar.

In 1867 one of the miners exploring the White Pine District was given a heavy piece of silver chloride by a local Indian in return for a purloined pot of beans (as the story goes). He and some pals located the ground it came from and began working it. The find was high on what quickly became known as Treasure Hill, and as others heard about it, they joined the search for more. By the time the first snow fell, a rough little city had built up among the mines of the local rock in plentiful supply, and lumber freighted in from afar.

Treasure City grew up there naturally enough. But “natural” at 8,700 feet in these mountains includes no water, freezing winters, avalanches, fierce gales, no firewood, uncertain travel and no services.

“Treasure City has ten months of winter and two months of exceptionally cold weather”, somebody pointed out, and a townsite was platted on more or less level ground at the foot of Treasure Hill’s north side, 900 feet lower down.

In June 1868 a saloon, Hamilton’s first frame structure, was built to accommodate the 30 residents living around it in tents. Assays of the ore from the claims on Treasure Hill showed exceptionally rich values, and the news inspired a hectic “Rush to White Pine”. In August a post office was established.

Over the summer Hamilton grew to accommodate the thousands of hopeful new citizens, some of them coming by train from the east and west coasts, and making their way south from Elko via stagecoach, freight wagon or afoot.

A letter to the Alta Californian from Treasure City in January 1869 stated “there were four deaths [here] on the 9th inst. The weather is very severe, and several persons have been badly frozen. Board is from $15 to $18 per week, exclusive of lodging, which is difficult to obtain at $1 per night. Little or no work is being done on any of the undeveloped claims. Persons anticipating a visit to the new district are cautioned not to do so before spring.”

But people came anyway. The mid-winter population at Hamilton was nearly 600 idle hands, and in the spring of 1869 the rush was on in earnest. By the time the roads were passable in the higher altitudes, a half-dozen stagecoach lines were running to Hamilton on a regular basis, bringing 75 to 100 eager new arrivals every day, and carrying away the already-disappointed. When White Pine County was organized in March 1869, Hamilton was named the county seat, and by summer’s end the town’s promoters were boasting about a city of 10,000 — no, 12,000!

But people came anyway. The mid-winter population at Hamilton was nearly 600 idle hands, and in the spring of 1869 the rush was on in earnest. By the time the roads were passable in the higher altitudes, a half-dozen stagecoach lines were running to Hamilton on a regular basis, bringing 75 to 100 eager new arrivals every day, and carrying away the already-disappointed. When White Pine County was organized in March 1869, Hamilton was named the county seat, and by summer’s end the town’s promoters were boasting about a city of 10,000 — no, 12,000!

For such a mighty city to suddenly burst into life in that remote place, the mines that supported it must be inexhaustibly rich! Indeed, they had already produced more than $22 million! This would be bigger than the Comstock!

When winter closed in again, though, Treasure City’s business community lost heart. In January 1870 the White Pine NEWS, edited by W.J. Forbes (who had come to White Pine to run a saloon but had fallen back into journalism), moved from its frozen aerie down to Hamilton, joining an exodus of attorneys, brokers of every kind, a wide variety of entrepreneurs, storekeepers and others who preferred staying warm over proximity to the mines.

Over 13,000 claims were located on Treasure Hill in less than two years, although few of them were ever actually worked. From those few, however, silver practically gushed.

Until it didn’t. The mines were rich, but most were shallow, and by the end of 1870 the boom was over. The census that year counted 1,920 residents of Treasure City, 3,913 in Hamilton and 932 in Shermantown.

On June 27 1873 Alexander Cohn decided to burn down his tobacco shop in Hamilton for the insurance, and to make sure the firemen couldn’t put out the fire, he closed the valve on the main water supply to the city. The entire business district burned except for two structures, and even though the mad rush was over, the city was rebuilt because it was the county seat and the center of business and finance for the region. When Treasure City suffered a major fire the next year, very little was rebuilt.

On June 27 1873 Alexander Cohn decided to burn down his tobacco shop in Hamilton for the insurance, and to make sure the firemen couldn’t put out the fire, he closed the valve on the main water supply to the city. The entire business district burned except for two structures, and even though the mad rush was over, the city was rebuilt because it was the county seat and the center of business and finance for the region. When Treasure City suffered a major fire the next year, very little was rebuilt.

The 1880 census showed the district had fallen on seriously hard times. Hamilton had only 117 voters, Eberhardt, the settlement of about 200 that grew up around the mill processing ore it received via aerial tramline, was down to 49. Treasure City had only 14 voters.

The 1880 census showed the district had fallen on seriously hard times. Hamilton had only 117 voters, Eberhardt, the settlement of about 200 that grew up around the mill processing ore it received via aerial tramline, was down to 49. Treasure City had only 14 voters.

There was another fire at Hamilton in 1885, and this time the Court House burned. In 1887 the White Pine County seat was moved to Ely. That was the end for Hamilton, and it has been falling quietly to pieces ever since. Photos taken in the in the 1950s show the Withington Hotel facade beautifully intact, but now even the ruins have fallen into ruin and what was once the most elegant hotel between Denver and Virginia City is only a pile of bricks.

We spent most of an hour at the Hamilton cemetery, overgrown and mostly untended on the road north to Illipah which we took on our way back to US 50. This is the way the stagecoaches and freight wagons brought passengers and goods south from Elko and the Central Pacific Railroad. Below is the view northwest from the Hamilton-Illipah road as it crests a summit before dropping down toward US 50.

We spent most of an hour at the Hamilton cemetery, overgrown and mostly untended on the road north to Illipah which we took on our way back to US 50. This is the way the stagecoaches and freight wagons brought passengers and goods south from Elko and the Central Pacific Railroad. Below is the view northwest from the Hamilton-Illipah road as it crests a summit before dropping down toward US 50.

You are seeing the immense sweep of the Newark Valley, with the Diamond Range beyond, about 50 miles of timeless tranquility.

Dave….great article…the cabin my family has had the use of for the last 50 years is in Gilford Meadows…off of Duck Creek Valley in the Schell Creek Range…it was built in 1870 and has been designated as the oldest still standing and used bldg in White Pine County….there is still a big Donkey engine there…it was the site where all the timber for the mines in Hamilton at the time….when the mines died…they paid the contract w/the land….its still there…maybe someday…I can take you up……dye