The last time I was an agri-tourist was 42 years ago, when I was led inside, outside, through and around a pig farm in Aarhus Denmark, but my memories of it are still vivid and enjoyable. So at this year’s Eagles & Ag event in Carson Valley (our 2015 Event of the year, which you’ve already missed unless you were there) Robin and I signed up for the ranch tours.

The last time I was an agri-tourist was 42 years ago, when I was led inside, outside, through and around a pig farm in Aarhus Denmark, but my memories of it are still vivid and enjoyable. So at this year’s Eagles & Ag event in Carson Valley (our 2015 Event of the year, which you’ve already missed unless you were there) Robin and I signed up for the ranch tours.

The water birds, the shore birds, the raptors that are everywhere, and especially the eagles among the newborn calves, get most of the press and most of the attention from the hundreds who attend — this is a photographer’s dream photo shoot.

The water birds, the shore birds, the raptors that are everywhere, and especially the eagles among the newborn calves, get most of the press and most of the attention from the hundreds who attend — this is a photographer’s dream photo shoot.

But as beautiful as they are, the birds won’t talk to you and the ranchers will. There were two ranch tours (as distinct from the barn tours, which are called “Owl Prowls”). On Saturday we visited the Stodieck Farm, selected for its “traditional” profile, and on Sunday we traipsed around another historic ranch, transformed over the past 14 years into a very modern variation on the theme.

Stodieck Farm

Stodieck Farm

The Stodieck Farm is on the east fork of the Carson River, south of Minden between Gardnerville to the east and Highway 88 to the west. Even though it is the second oldest family-operated ranch in the Valley dating from its 1868 purchase by Fred and Betty Stodieck (a previous owner had sold out for a saddle and a horse to put under it).

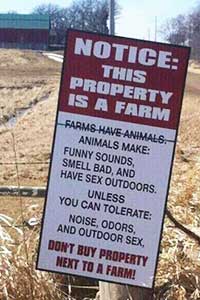

One of the outbuildings at the edge of the incoming drive is considered the oldest surviving structure in the Valley. It bears a white sign with big red letters: DOGS BITE.

One of the outbuildings at the edge of the incoming drive is considered the oldest surviving structure in the Valley. It bears a white sign with big red letters: DOGS BITE.

Today’s proprietor is also named Fred Stodieck, and he raises Angus-cross cattle and alfalfa here more or less the way his great-great-grandfather did, but with 21st century twists here and there. His 240 acres of alfalfa grow in laser-leveled fields — he also laser-levels his neighbors’ fields as a side business — and he rents acreage to California garlic growers who start their seed crops here, then transplant them back to California to mature.

“We get the rent money and a tilled field when they leave,” Fred told us. “We also get a lot of garlic that’s left there unharvested and if we leave it there the voles will move out of that field — they hate garlic. And there’s the possibility of white rot fungus, which is hard to eradicate.”

Things are especially busy on the Farm just now, what with the calves coming and repairing damage from the violent windstorm that tore through the Valley a few days before. Eighteen of the towering trees on the farm were downed, he said, and emphasized that the trees are more than ornaments on the landscape, they are also essential bird habitat and valuable windbreaks.

His newborn calves are inoculated within hours of birth with the help of a mechanical “Calf-Catcher”. Laser levelers are commonplace these days, but Calf-Catchers are still a novelty. This one attaches to the side of an ATV but instead of being a side-car, it is a side-cage, with no bottom and a spring-operated gate. The cowboy, or in this case the cowgirl, slips up on the uncomprehending bovines and gathers in the calf like an infielder. Then she can stop the ATV and administer the medications without having to fend off the new mom.

|

|

|

|

|

“It’s a safety issue.” Fred says. “There’s no comparison to going out there alone, the cows trying to protect their newborn calves, and you trying to meddle with them. That can be trouble any time, and sometimes it’s big trouble.”

But on this warm sunny afternoon serenity reigned, and trouble seemed banished from the world.

Comstock Seeds

Ed Kleiner moved to the Carson Valley from a crowded acre in an industrial section of Reno 14 years ago. He has spent the years since transforming a more-or-less traditional 19th century dairy ranch into a 21st century agribusiness specializing in native seed acquisition, drought tolerant agriculture, grasses, shrubs and wildflowers.

He has spent the years since transforming a more-or-less traditional 19th century dairy ranch into a 21st century agribusiness specializing in native seed acquisition, drought tolerant agriculture, grasses, shrubs and wildflowers. He has experimented in a variety of ways, from a small planting of wine grapes and a constructed wetland that treats the household effluent.

He has experimented in a variety of ways, from a small planting of wine grapes and a constructed wetland that treats the household effluent.

Ed gathers native seed from all over the west, and sells it by the bag to highway departments, mining companies, utilities, reclamation projects of all kinds. He will make up a special blend to order as well as standard mixes for particular locations and purposes, from drab, hardworking erosion-minimizers to exuberant wildflower mixes.

|

|

And always trying something new. He planted Franzenac vines to produce Nevada-grown grapes for a nearby Nevada winery. This is how he learned what a micro-climate is, and how very cold his own personal micro-climate is in winter.

“There are grapevines there to the west, actually up into the foothills a little way,” he told us, pointing it out. “They’re flourishing. But of the 300 I planted here, only 20 survived their first winter.” Not as big a deal as it might have been because while the vines were freezing the winery was suffering reverses and the deal was off. Ah, the country life!

He told us about seeing two gulls in mid-air, furiously flapping their wings and fighting chest-to-chest over a struggling vole. Does he feel like that vole sometimes, I wondered, caught between the unyielding weather and the uncaring marketplace?

He told us about seeing two gulls in mid-air, furiously flapping their wings and fighting chest-to-chest over a struggling vole. Does he feel like that vole sometimes, I wondered, caught between the unyielding weather and the uncaring marketplace?

And it’s not just the cold. In the next field over he planted a variety of popular annuals, but the dry winds and the dust limited production and prompted him to change to the perennial native blue penstemons which flourish there now.

His livestock are as eclectic as his crops.To show us one of his favorites, an orphan brought out of the southern Nevada desert for him to shelter, he went into a utility room and brought out a cardboard box. He reached into it, pulled out some wadded-up newspapers, and then, like a stage magician, he brought out a hibernating desert tortoise and held it up for us to see. He explained the purpose of the program, which is to move the critters eventually to new habitat, and then he put the slowly twitching tortoise back in the box and the box back into the closet.

His livestock are as eclectic as his crops.To show us one of his favorites, an orphan brought out of the southern Nevada desert for him to shelter, he went into a utility room and brought out a cardboard box. He reached into it, pulled out some wadded-up newspapers, and then, like a stage magician, he brought out a hibernating desert tortoise and held it up for us to see. He explained the purpose of the program, which is to move the critters eventually to new habitat, and then he put the slowly twitching tortoise back in the box and the box back into the closet.