We are in Battle Mountain for the World’s Fastest Human-Powered Speed Challenge, which is a contest to see whose bicycle can go fastest on five miles of straight, flat Highway 305 about 15 miles south of town on the road to Austin.

Battle Mountain is on the heavily-traveled I-80 and all, but it has never been known as a destination for enthusiasts of any kind except hunters, who hold an annual chukar hunt here each fall. Yet Battle Mountain is world-famous (in a small way) for hosting this most prestigious event in the world of speed bicycling each year.

Battle Mountain is on the heavily-traveled I-80 and all, but it has never been known as a destination for enthusiasts of any kind except hunters, who hold an annual chukar hunt here each fall. Yet Battle Mountain is world-famous (in a small way) for hosting this most prestigious event in the world of speed bicycling each year.

This isn’t bicycling the way the paper boy did it in your grandfather’s day, this is bicycling the way Elon Musk might do it tomorrow.

This isn’t bicycling the way the paper boy did it in your grandfather’s day, this is bicycling the way Elon Musk might do it tomorrow.

The riders start by staying fit. Then someone — more likely a team of someones — designs a combination of sprockets, gears and a body support, squeezed inside an aerodynamic fiberglass skin created for the tightest fit possible.  There’s no standard design for assembling the parts (including the cyclist), and in fact within the limitations of the materials and given the pursuit of speed for speed’s sake, there’s a wide variety of approach.

There’s no standard design for assembling the parts (including the cyclist), and in fact within the limitations of the materials and given the pursuit of speed for speed’s sake, there’s a wide variety of approach.

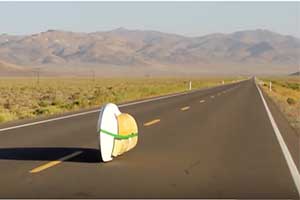

One of the most enjoyable parts of this competition is watching the cyclists struggle into their recumbent steeds. Some are able to see ahead through a tiny ‘windshield’ slit in the skin, while others lie so nearly horizontal that their view of the road is delivered from an outside camera to a small video receiver clipped to the tiny handlebars.

One of the most enjoyable parts of this competition is watching the cyclists struggle into their recumbent steeds. Some are able to see ahead through a tiny ‘windshield’ slit in the skin, while others lie so nearly horizontal that their view of the road is delivered from an outside camera to a small video receiver clipped to the tiny handlebars.

Others require the driver to slither into the pod and inch into place among, between and around the internal machinery. At least one such driver ends up riding backwards, steering with the help of a camera facing forward, another is facing forward but lying on his belly in a kind of hammock, and kicking straight forward and straight back with his feet instead of in circular fashion.

Others require the driver to slither into the pod and inch into place among, between and around the internal machinery. At least one such driver ends up riding backwards, steering with the help of a camera facing forward, another is facing forward but lying on his belly in a kind of hammock, and kicking straight forward and straight back with his feet instead of in circular fashion.

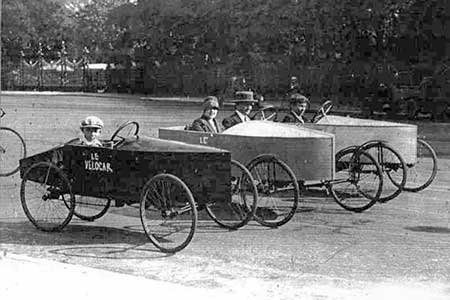

It began in 1973 when Chester R. Kyle, a professor at Cal State Long Beach, offered University credit for a lab project studying the friction and drag caused by different types of bicycle tires. The students discovered to their surprise that the tires don’t make much difference; it is wind resistance that causes 90% of the drag at racing speeds. So they set about reducing wind resistance and in late 1974 demonstrated a fully enclosed bike — and broke the bicycle speed records for 200m, 500m, 1000m and 1 mile from a flying start.

It began in 1973 when Chester R. Kyle, a professor at Cal State Long Beach, offered University credit for a lab project studying the friction and drag caused by different types of bicycle tires. The students discovered to their surprise that the tires don’t make much difference; it is wind resistance that causes 90% of the drag at racing speeds. So they set about reducing wind resistance and in late 1974 demonstrated a fully enclosed bike — and broke the bicycle speed records for 200m, 500m, 1000m and 1 mile from a flying start.

An All-Comers race was held April 5, 1975 on a quarter-mile drag strip and “fourteen of the strangest pedal-powered vehicles in history” participated. The next year there were 26, and 50 or 60 were common after that, with races conducted by enthusiasts at various places around the world.

An All-Comers race was held April 5, 1975 on a quarter-mile drag strip and “fourteen of the strangest pedal-powered vehicles in history” participated. The next year there were 26, and 50 or 60 were common after that, with races conducted by enthusiasts at various places around the world.

In 1994 an engineer named Matt Weaver built a fully-enclosed bicycle he called “Cutting Edge” and started looking for an ideal race course to attempt the world speed record. He traveled more than 2,000 miles in California and Nevada searching for a long, straight flat stretch of paved road and found four of them. Three were unsuitable for various reasons, but one was perfect: Battle Mountain.

Smoothest Pavement on Flattest Road

Roads with lower comparative traffic volumes such as Nevada 305 are often resurfaced using the cheaper chip seal method, in which the asphalt binder is laid down and aggregate gravel then goes on top as the new roadway surface. |

From the official history of the IHPVA: “The Battle Mountain race has been run every year since 2000. World records have risen from 72.74 mph in 2000 to 83.13 mph in 2013. The race course has proven ideal for high speeds with human powered vehicles. Since 2000 the world HPV record has been broken seven times at Battle Mountain. In effect this competition has become the yearly World Championship. So after nearly 40 years, the original goal of the IHPVA, to see how fast a vehicle can go under human power, is still in full force.”

Make that eight world IHPV speed records: on Wednesday afternoon, after we had left for home, Todd Reichert of Canada broke his own record (86.65 mph, set last year breaking the Delft/Amsterdam team‘s record of 83.13 mph set here two years previously.) with a speed of 88.26 mph and there were still two more days to go.

Human powered bicycle speed racing is a most unlikely spectator sport, and watching it isn’t easy. The instructions for spectators spell out the difficulties: limited parking and no services. Heats are conducted early each morning and late each afternoon of race week, with short intervals during the active periods to let the highway traffic through. There is no parking allowed along the road because the bikes do crash from time to time (hay bales are placed as bumpers where needed) and it’s better they don’t crash into a parked car.

There are shuttles from town, but you can’t see the whole event at once no matter where you go or how you get there.

Our solution was to drive all the way to the launching area (the race is northward, back toward town). Here we watched a half dozen bikes roll out onto the pavement, each enclosed rider pushed one at a time to a sometimes wobbly start and released with a chase car following behind in case of mishaps. The rider has most of the 2-1/2- or 5-mile run to get up to speed and are then measured over the final 200 meters.

While the teams in the next heat were preparing their bikes, traffic was again allowed through and we went with it back toward town. There are catch areas at 2-1/2 and 5 miles, and even a small set of bleachers where you can sit and watch the bikes flit past. It is an odd and unaccustomed — and beautiful — sight that catches the eye and excites interest. We are coming back for more next year.

It’s not that we have a favorite among the teams (six of them from Universities) that fielded bikes and riders, we don’t. We just like the idea of it, and the way that idea has become reality — all the thinking and tinkering and craftsmanship and determination that has not become a Mega-Event like Burning Man, but remains an astonishing once-a-year spectacle on this sparsely-traveled road.

It’s like Burning Man in the sense of burning the candle late into the night experimenting with weight distribution and aerodynamic purity for the sake of speed, of the burning muscles required to achieve top speed and of the burning ambition pushing the bikes faster, ever faster.

We’ll probably stay again at the pet-friendly Battle Mountain Inn; the Super 8 serves as unofficial home camp for many of the teams and there are a handful of other motels mostly booked well in advance. We’ll dine out at El Aguila Real on the Main Street, the Hide Away steak house on Broad Street across from the Civic Center, which serves as headquarters for the event between races. The Owl Club is an All-American cafe facing the railroad tracks on Front Street, and the Colt is at the far western edge of town. The Cook House Museum is at 855 Broyles Ranch Road, a short distance west of the Civic Center and well worth a visit. An Indian Casino is in the permitting phase, awaiting construction across I-80 to the south of town, and that will doubtless add to the welcome.

For those who like to greet the dawn with a latte in hand there is Bakker’s Brew, just south of the Civic Center and around the corner to the west. I am in awe of their willingness to open at 4:30 am, and I support it enthusiastically.

For those who like to greet the dawn with a latte in hand there is Bakker’s Brew, just south of the Civic Center and around the corner to the west. I am in awe of their willingness to open at 4:30 am, and I support it enthusiastically.

One of the big surprises this year was the Japanese team, the most successful first time team ever, with Ryohei Komori going 82.03 mph on his final run.

It is conceivable — maybe inevitable — that on a day not far off, when all the factors are benign, a human being from Japan or Canada or somewhere else will achieve 90 mph on a bicycle — and when that happens it will be in Battle Mountain.

My report is that of an appreciative outsider, and I’ve drawn on this meticulous record of the event by an appreciative insider for some of the facts and some of the photos above, on this highly informative site for others, and for the terrific action photos from the Flickr posts of Jeff Wills. Here is jnyyz’ comprehensive wrap-up of the event.

To provide a very smooth roadway surface for drivers and for World Human-Powered Speed Challenge participants, NDOT utilized open-grade paving on certain sections of State Route 305. In open-grade paving, aggregates (the small gravel used in roadway surfaces) is mixed with an asphalt binder at a mixing plant and rolled down together, producing a very smooth new roadway surface.

To provide a very smooth roadway surface for drivers and for World Human-Powered Speed Challenge participants, NDOT utilized open-grade paving on certain sections of State Route 305. In open-grade paving, aggregates (the small gravel used in roadway surfaces) is mixed with an asphalt binder at a mixing plant and rolled down together, producing a very smooth new roadway surface.

What time does the shuttle leave on Monday afternoon?