Tuscarora’s great event takes place every other year, usually over the Memorial Day weekend: Open Studios, during which visitors may tour the ateliers and meet the “sensitives” (as my friend Buckeye Blake calls them) who make the art. This year the event was delayed to coincide with the dedication of the community’s lovingly restored “Tuscarora Society Hall”, the happy ending to a grueling ten-year effort by the small community.

Tuscarora’s great event takes place every other year, usually over the Memorial Day weekend: Open Studios, during which visitors may tour the ateliers and meet the “sensitives” (as my friend Buckeye Blake calls them) who make the art. This year the event was delayed to coincide with the dedication of the community’s lovingly restored “Tuscarora Society Hall”, the happy ending to a grueling ten-year effort by the small community.

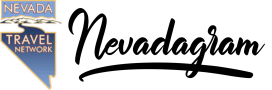

Photo by F.A. Martin

Tuscarora is about 50 miles north of Elko via the Mountain City Highway (Nevada 225) and Nevada 226. There is no store. No cafe, no saloon, no commerce in the usual sense. There are only homes, studios, workshops, the post office and now the Society Hall, which will be staffed by volunteers on August weekends.

Photo courtesy FsTIV

Tuscarora began as a campfire in the sagebrush with a small group of Union civil war veterans sitting around it. This was July 1867, and they were so elated with their placer mining prospects on the Owyhee River that they were already dreaming up a townsite with a plaza at its center, a bank here, a hotel there, an Opera House, saloons sprinkled all around and the whorehouses back here — and then

puzzled over a name for it. One of them proposed Tuscarora, after the Union gunboat he had served aboard during the war, and it stuck.

Photo courtesy FsTIV

After its second winter Tuscarora was still a tent camp of fewer than a dozen placer miners, making a hard living, but on May 10 the transcontinental railroad was completed and all the Chinese workers were cut loose. The 1870 census counted 105 Chinese and 15 whites in the district, most, if not all of them working long toms and riffle boxes in the Owyhee and its tributaries.

Photo by Max Winthrop

In 1871 William O. Weed made a gold and silver strike on the flank of Mt. Blitzen a couple of miles to the northeast, and Tuscarora moved, miners, tents, name and all. The original site is almost forgotten now, difficult to find and even more difficult to get to.

Photo by Max Winthrop

Photo courtesy FsTIV

In 1900, 669 remained. The two stores had closed by then, and the building housed the local Masonic Lodge until 1938. The population hasn’t been above 50 since the 1920s, when the structure was put to a variety of uses but was principally a saloon. Just now the population is back down to about a dozen who winter through, plus maybe 20 more who return every spring and depart every autumn.

Photo by Max Winthrop

Dennis Parks helped put Tuscarora on the art map. He came in 1972 with his young family, to work in solitude as a potter, and eventually to establish his now famous pottery school. His memoir “Living in the Country Growing Weird” is a Nevada classic.

In the 1980s a mining company attempted to obliterate the little town by pit mining here, but the combination of community resistance, public condemnation and fluctuations in the gold market saved it.

In the early 1990s John Fahnstock finally succeeded in buying the building after years of trying, and he rebuilt the western wall, which had failed; it’s thanks to him the building is still standing. A group of local

Photo by Max Winthrop

citizens formed a private non-profit organization, The Friends of Tuscarora and Independence Valley, and began the project by raising $20,000 in private funds to purchase the building from John. The group then gave the property to Elko County, and applied for grant funding to complete the transformation from a crumbling ruin to a remarkable living artifact, celebrating the

Photo by Max Winthrop

long and colorful history of Tuscarora and the Independence Valley.

So did Jan Peterson’s cemetery tour, which provided intriguing glimpses of life in and around Tuscarora since the discovery. The Curieux, the Packers, the Van Normans, the Pattanis, all in their quiet rows. Guitardo Pattani died young in 1902. He was out with a

Photo by Max Winthrop

Photo by Max Winthrop

couple of his cousins rounding up strayed horses, and he climbed a power pole to get a good look out over the rumpled landscape.

“Hey, Guitardo,” one of the boys yelled up at him, “I dare you to touch the wire!”

Rest in Peace, Guitardo.

Over in a brushy corner of the cemetery lies Carl Metzler, an old cowboy when he died in 1966. He walked with a limp he’d

Photo by Max Winthrop

acquired in 1940, during a visit to San Francisco.

Photo by Max Winthrop

He’d caught the Powell Street cable car down to the turntable at Market, walked into the big bank on the corner, and robbed it: just pulled out a pistol and demanded money! But he got shot in the leg instead, and hobbled back outside just in time to make his bloody getaway on an outbound cable car heading up the hill.

Photo courtesy FsTIV

After serving his time in Alcatraz, he came back to Tuscarora and went back to cowboying, but with the limp.

Most of the graves, monuments, markers and memorials are in traditional style, but some of the more recent entries suggest the current character of the place and its inhabitants.

Photo by Max Winthrop

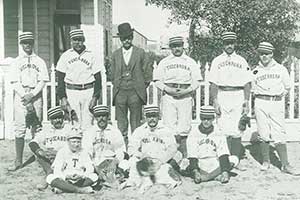

Tuscarora has produced one semi-famous (in his day) native son, although he’s not buried here: William George “Wheezer” Dell was born in Tuscarora June 11 1886, the first Nevada native to play professional baseball in the big leagues. I don’t know if he’s in that photo of the Tuscarora town team, but in 1912, age 25, he pitched three innings in two games as a right-handed reliever for the St. Louis Cardinals.

Photo courtesy FsTIV

He’s gone from the record books until he came back to pitch for the Brooklyn Robins from 1915 to 1917. He pitched one inning in the 1916 World Series, his lifetime major league ERA was 2.55 and he was a teammate of Zack Wheat and Casey Stengel.

After that he helped the Vernon (Los Angeles County) Tigers win three consecutive Pacific Coast League championships, 1918-1920. He was traded to the Seattle Indians in 1921, led the league in wins that year and helped them to the league championship in 1924, his last year as a player. He died in Big Pine California, age 80, in 1966.

Quick notes from beyond the mountains: Here’s a unique look at Piper’s Opera House in Virginia City . . . If it’s Not One Train, It’s Another — Summer Specials at Nevada Northern Railway . . .

Overheard at the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City: “Poetry happens when an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found its words. That’s why it’s rare and precious.”

Happy Highways,

David W. Toll