Luke Rizzuto was one of the people who thrilled when a centennial re-creation of the Great New York to Paris automobile race was announced.

He has a rare 1918 Chevrolet touring car with an overhead valve V8 engine — that’s right, Chevrolet made this engine from 1917 to 1919 and then abandoned it until 1955 — and he wanted to drive it across country following the route of the winning Thomas Flyer in 1908. So he set about seeking sponsors to defray the substantial cost to participate.

This video was made when Luke was trying at attract sponsors. When the race organizers went bankrupt, he decided to make the run anyhow. |

However, the organizers of the event became disorganized and eventually they cancelled their event. But Luke still wanted to do it. He didn’t want to do it alone — how can you recreate a great race with just one car? — so he passed the word around. With the help of his wife he set up a website, inviting like-minded car lovers to join him. No fees to pay, no organization to maintain, just get yourself and your car to a hotel in New Jersey on October 17 and be ready to pay your own expenses.

Counting Luke, his wife, chase car drivers, navigators and extra mechanics, 16 people showed up with six cars. Some of them, like Luke’s old Chevy, Ron Fowler’s 1930 Chevrolet Speedster and John Quam’s beautiful 1930 Chrysler roadster, were antique and classic beauties. Others were not so easy to classify. Ed and Janet Howle drove their 1967 VW beetle. Chris Bamford and Jerry de Jong drove a 1947 Dodge Special Deluxe sedan down from Edmonton Canada and joined the procession in Laramie Wyoming. Klaus and Maja von Deylen flew in from Germany and drove a rented Buick, and Alan Nagle came from Dublin to reunite with his old friend Harry Sperber and honor the promise they’d made to each other years before.

Counting Luke, his wife, chase car drivers, navigators and extra mechanics, 16 people showed up with six cars. Some of them, like Luke’s old Chevy, Ron Fowler’s 1930 Chevrolet Speedster and John Quam’s beautiful 1930 Chrysler roadster, were antique and classic beauties. Others were not so easy to classify. Ed and Janet Howle drove their 1967 VW beetle. Chris Bamford and Jerry de Jong drove a 1947 Dodge Special Deluxe sedan down from Edmonton Canada and joined the procession in Laramie Wyoming. Klaus and Maja von Deylen flew in from Germany and drove a rented Buick, and Alan Nagle came from Dublin to reunite with his old friend Harry Sperber and honor the promise they’d made to each other years before.

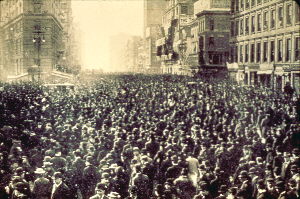

And there was Rodney Rucker, of Winslow Arizona, who drove a bright yellow two-seater chop-top hot rod made from a 1950 Peterbilt (powered by a 400 Cummins diesel) and called “The Petester”. Rod had completed rebuilding the engine, upholstering the seats and painting the body just in time to load it aboard a trailer and highball to New York where he arrived just in time for the start of the Race. The drive from the hotel parking lot in New Jersey to Times Square was the shakedown cruise for the huge machine, and fortunately everything worked perfectly.

And there was Rodney Rucker, of Winslow Arizona, who drove a bright yellow two-seater chop-top hot rod made from a 1950 Peterbilt (powered by a 400 Cummins diesel) and called “The Petester”. Rod had completed rebuilding the engine, upholstering the seats and painting the body just in time to load it aboard a trailer and highball to New York where he arrived just in time for the start of the Race. The drive from the hotel parking lot in New Jersey to Times Square was the shakedown cruise for the huge machine, and fortunately everything worked perfectly.

The same can’t be said for Brian and Melinda Perry and the 1940 Cadillac sedan they’d bought sight unseen: rusted brakes forced a stop for repairs. The caravan departed Times Square without them, enroute to Springville, a few miles south of Buffalo in upstate New York.

The same can’t be said for Brian and Melinda Perry and the 1940 Cadillac sedan they’d bought sight unseen: rusted brakes forced a stop for repairs. The caravan departed Times Square without them, enroute to Springville, a few miles south of Buffalo in upstate New York.

This was the hometown of George Schuster, the intrepid mechanic who kept the Thomas Flyer in good repair until it reached Ogden Utah. There he was handed the keys and promoted to driver for the rest of the journey. It was also one of the few places along the way where the modern drivers were greeted with more enthusiasm than curiosity, as some 700 school children waved American flags when the old cars drove in for a visit.

That was October 20, and over the following days, other enthusiasts joined the procession for various periods of time, driving a variety of fabulous cars as the caravan rumbled westward through Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and Illinois, then Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah and Nevada, still closely following the route of the original race.

That was October 20, and over the following days, other enthusiasts joined the procession for various periods of time, driving a variety of fabulous cars as the caravan rumbled westward through Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and Illinois, then Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah and Nevada, still closely following the route of the original race.

Mechanical difficulties plagued several of the cars, but the most dramatic calamity befell Ray and Pat when the 1930 Chevrolet Speedster lost its throw-out bearing in Montello, in far northeastern Nevada. Efforts to repair it were futile, and replacement parts were unavailable (although someone suggested that Walt, at the Birch Brothers Garage in Ely, might be able to help), so they did what you have to do in that situation: they jammed it into gear and drove on.

A new documentary about The Great Race is being produced in Canada. |

Unable to shift gears, they finessed the traffic lights in Wendover, and weathered the rain that crashed down as they pressed on to Ely.

The rain had stopped when they pulled into the parking lot behind the Hotel Nevada, but Walt couldn’t be found so they went to Sportsworld to buy a hockey puck in hopes of fabricating a new bearing. To their astonishment, this big sporting goods store doesn’t stock hockey pucks. “In Canada every store has hockey pucks,” they told me.

A second call to Walt was successful, and they explained they needed a throw out bearing for a 1930 Chevrolet Speedster. Silence, and then Walt said, “I think I have something that will work.” They hurried down

Aultman Street to the garage, but Walt wasn’t there. Spirits sinking, they waited . . . and waited . . . until Walt appeared holding the throwout bearing for a 1930 Chevrolet Speedster. “Is this what you’re looking for?” he asked.

Another hour on the wet asphalt under the car and the speedster was as good as new.

The next morning I joined the Tonopah-bound procession representing the 21st century in a new Prius and wondering what I was doing with this band of crackpots. As it turned out, I was having a blast. These people had found a new way to enjoy and appreciate driving across Nevada, and it was great fun.

The next morning I joined the Tonopah-bound procession representing the 21st century in a new Prius and wondering what I was doing with this band of crackpots. As it turned out, I was having a blast. These people had found a new way to enjoy and appreciate driving across Nevada, and it was great fun.

I learned a lot about the 1908 race of course — George Schuster’s great-grandson Jeff Mahl was a part of the group — and I learned some more about getting off the pavement in remote areas of Nevada too. US 6 is the direct route between Ely and Tonopah these days, but it didn’t exist when the Thomas Flyer came careening across the landscape here. Schuster and his companions had gone west from Ely to Hamilton, and then south following rutted wagon roads from ranch to ranch.

When we came to a faint track angling away from the highway toward the distant mountains we stopped and marveled:

When we came to a faint track angling away from the highway toward the distant mountains we stopped and marveled:  here were the original ruts that the Flyer followed! Luke Rizzuto drove his car off the trailer and out into the sagebrush on the old remnant of road. Bliss!

here were the original ruts that the Flyer followed! Luke Rizzuto drove his car off the trailer and out into the sagebrush on the old remnant of road. Bliss!

But then the car goes back up on the trailer again as we resume our progress across Railroad Valley.  Before long we turn east onto a gravel road and proceed through Nevada’s only oil field to the east side of the valley and then turn south to the Blue Eagle Ranch. The old cars are grinding merrily along, the wind loud in the drivers’ ears over the racket of the engines. In the Prius I am listening to NPR.

Before long we turn east onto a gravel road and proceed through Nevada’s only oil field to the east side of the valley and then turn south to the Blue Eagle Ranch. The old cars are grinding merrily along, the wind loud in the drivers’ ears over the racket of the engines. In the Prius I am listening to NPR.

The Flyer came this way too. This ranch house, moved first from Belmont to the long-vanished mining town of Liberty, and then here in 1904, greeted Schuster back then, but he didn’t linger long and neither did we.

Another 45 miles south brings us to pavement again, the Extra Terrestrial Highway (Nevada 376). We turn west, toward Warm Springs, and pull in at the Twin Springs Ranch for another touchstone of history. Schuster had crossed the little stream here, hefting boulders into the soft-bottomed streambed to make it fordable, but while struggling up the far bank he broke some teeth off the pinion gear and cracked the transmission case. The Flyer was grounded.

Another 45 miles south brings us to pavement again, the Extra Terrestrial Highway (Nevada 376). We turn west, toward Warm Springs, and pull in at the Twin Springs Ranch for another touchstone of history. Schuster had crossed the little stream here, hefting boulders into the soft-bottomed streambed to make it fordable, but while struggling up the far bank he broke some teeth off the pinion gear and cracked the transmission case. The Flyer was grounded.

Good grief. Now what? He bought an old gray horse for $20 and set out at dusk for Tonopah where he knew there was at least one other Flyer he could rob parts from. But he got lost in the darkness and happened across Stone Cabin. His knock brought a woman with a shotgun to the door. She was alone — the other folks from the ranch had gone to Tonopah to await the arrival of the racers. She wouldn’t let him into the cabin, but directed him to a corral for his horse and a rough leanto for himself.

Schuster nested up for the night, but was awakened by the arrival of a car carrying a search party from Tonopah. They drove him into town where he persuaded a local dentist to part with his drive train, which he then drove back out to Twin Springs and installed on the Flyer.

Schuster nested up for the night, but was awakened by the arrival of a car carrying a search party from Tonopah. They drove him into town where he persuaded a local dentist to part with his drive train, which he then drove back out to Twin Springs and installed on the Flyer.

One of the highlights of the visit was locating the exact point at which the Flyer had foundered in the creek that winds through the ranch. Rancher Joe Fallini not only greeted us hospitably, pointing out the structures that had been here in 1908, he also pried open the doors to an old shed to reveal the Model T his father had given him many years before. For an audience of car lovers it was like unveiling the Mona Lisa.

We were in Tonopah for dinner, up early for a photo shoot at the same spot where the Centennial celebration took place in March, and then on to Goldfield for a magnificent breakfast at the Northern Saloon and Cafe. From there the cars chugged off toward Beatty, Rhyolite, Death Valley, Ridgecrest, Fresno, San Jose and the Ferry Building at the foot of Market Street in San Francisco. That’s where this exercise in four-dimensional nostalgia came to an end . . . or maybe not. At the final Drivers’ Meeting in Nevada, at Tonopah Station, it was suggested that next year they tackle the second leg of the race by shipping their cars to Vladivostok and driving across Siberia to Moscow and then on to Paris. Rod Rucker suggested a mighty pie-fight, like the one that ended the Tony Curtis movie, but it was clear that Siberia was a more seductive option. You can find many more details of the adventure here.

We were in Tonopah for dinner, up early for a photo shoot at the same spot where the Centennial celebration took place in March, and then on to Goldfield for a magnificent breakfast at the Northern Saloon and Cafe. From there the cars chugged off toward Beatty, Rhyolite, Death Valley, Ridgecrest, Fresno, San Jose and the Ferry Building at the foot of Market Street in San Francisco. That’s where this exercise in four-dimensional nostalgia came to an end . . . or maybe not. At the final Drivers’ Meeting in Nevada, at Tonopah Station, it was suggested that next year they tackle the second leg of the race by shipping their cars to Vladivostok and driving across Siberia to Moscow and then on to Paris. Rod Rucker suggested a mighty pie-fight, like the one that ended the Tony Curtis movie, but it was clear that Siberia was a more seductive option. You can find many more details of the adventure here.