Somewhere in the rocky high ground North east of Nevada’s pyramid Lake there’s a white Mustang mare that Gordon Fraser and I would like to bring out one day.

She’s one of three or four hundred wild horses still roaming that remote corner of the Paiute Indian Reservation, and she’s as fast at has fiercely beautiful as the lightning. When Gordon took me out roping Indian-fashion, she was the big one that got away.

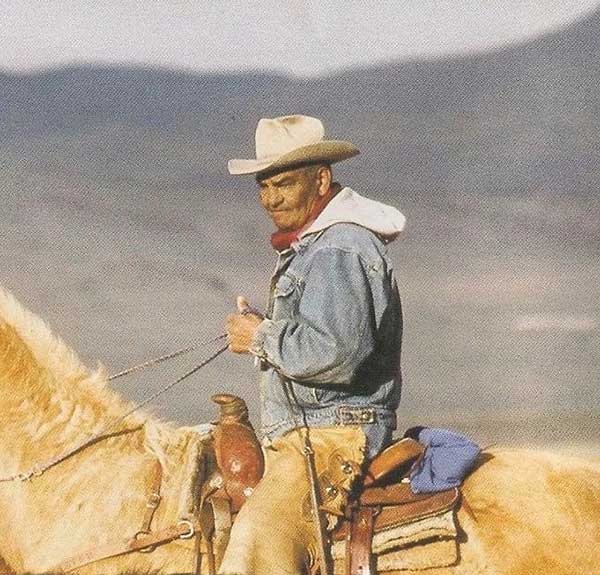

I met Gordon a couple of years ago at Sutcliffe, the two saloon settlement on the west shore of the lake. He’s a slender, dark skinned Paiute of medium height and athletic build, and more often than not he wears his Piratical features wrapped up in a wild grin. He’d come into the bar on late afternoons slapping the dust out of the blue baseball cap and have a beer or two before going home from his road maintenance job. Dan Hellman, the former L.A. Angels pitcher who worked at the bar, introduced us one day. After Gordon had gone home, Dan told me about him.

When Arthur Miller had come out to spend a couple of summer months at the ramshackle dude ranch sprawled under the cottonwood trees at Sutcliffe, they had been fascinated by the wild horses in the nearby mountains, so fascinated that he hired one of the commercial ropers to take him out and show him how the large-scale captures were made.

“it was Gordon who showed him the operation,” Dan told me, “And from what Gordon told him showed him, he wrote The Misfits for Marilyn Monroe, who was his wife then, and Clark Gable. And when they came back out here to make the movie, it was Gordon who handled the mustangs for them and who did the roping that Gable and Montgomery Clift got the credit for on the screen.

Wild horses have been grazing Nevada’s isolated mountain ranges and secluded valleys since the first of them strayed from the pioneers’ wagon trains more than a century ago. Their numbers grew over the years with the addition of strays from army posts, farms and ranches and by natural increase until, less than 40 years ago there were several times more wild horses in Nevada than people.

For much of the time they were ignored, except by the angry farmers those mares they have lured away and whose crops they poach and by the cowpunchers who occasionally captured them do use as saddle horses. But in the 1930s the horses became valuable as an inexpensive source of meat for pet food, and large-scale hunts were organized. By the 1950s, when Arthur Miller came for a look, commercial hunters were using aircraft at the alkali flats where they could do it with relative ease from trucks.

Legislation now protects the horses from wholesale slaughter, but Indians still range the sage-clumprd hills in search of the tough, swift beasts. For them the remaining wild horse bands are a source of fine saddle stock.

The next time I saw Gordon I asked him if I could go along when he went out again to rope mustangs. He said I could come along with him and four other Indians the next weekend.

But that weekend it rained, and the following weekend he had to help his brother-in-law move some cows, and the weekend after that something else came up, and so on for four months. It was a Friday afternoon in August when we finally did meet again at Sutcliffe to head up into the hills.

By the time I got there, two of the men had already started out on the hard 50-mile journey around the north end of the lake. They were driving an old stock truck with three saddle horses in it, and would set up camp ahead of us. The second stock truck rattled up with the rest of the horses shortly after I arrived. An hour or two later Gordon pulled in, his yellow pickup heavy with baled hay and tack. We set out in convoy, Gordon leading the way, the stock truck grinding after him and me following. It was soon dark, and we had to stop before going 25 miles. The lights on the stock truck wouldn’t go on.

We took turns tinkering with the wiring for more than half an hour without any luck, and finally set out again in close tandem so that the stock truck could steer by Gordon’s headlights upfront and by mine poking around the left side from behind. We bounced in a close-coupled knot over a series of dusty, rock-cobbled tracks that eventually wound up into the chalky pastel mountains above the northeast shore of the lake. Gordon called a stop every mile or two to Look for signs by the headlights. He’d hunker down on his haunches in the trail and trace the faint markings with his finger. I was enchanted with the sight of an authentic Indian tracker until I realized that he was not looking for unshod hoofprints, but for tire tracks. He was worried that the first stock truck had got off the road somewhere.

It was nearly midnight when we dropped into the hollow at the head of Wildhorse canyon. The truck wasn’t there.

The Indians corralled the horses and put their bedding into an old cowboy’s line shack while Gordon drove off to backtrack and see what had become of the other truck. An hour later two pairs of headlights came jiggling over the crest of the road. The stock truck missed the turn into Wildhorse canyon (even though it was marked by a sign) and had been wandering for nearly four hours over little-used desert roads far to the north. The fact that the Indians had got lost on the reservation where they lived all their lives was foreboding. What had I got myself into?

In the bright, fragile light of dawn I was standing on the stoop of the old shack sipping gingerly at a cup of scalding coffee when one of the men extended his arm toward a hillside three or four miles away. Peering where he pointed I could barely make out for specks against the sage mottled hillside. “Bay stallion and three mares,” he said. “Just watered and moved down to graze.”

The men hurriedly saddled their horses and divided into two groups. Two of the men would ride out to flank the browsing mustangs while the others took to higher ground across the valley. The hazers would sweep down from above and behind the horses, stampede them across the valley, and there the ropers, waiting on fresh horses, would gather them in. I was stationed at the brow of the hill above our camp to prevent escape by waving my arms and shouting and running back and forth if they veered away.

It didn’t work out that way. The ropers rode off over one hill, the hazers over another, and I waited, watching the four distant specks through binoculars. They were moving all right. Half an hour passed with no sign of the Indians. The four shapes moved slowly downslope. I studied them — and studied them some more.

What the hell! Those shapes weren’t horses — they were cows!

I began searching the hillsides for some sign of the riders, the suspicion welling up in me that they had all ridden, laughing like crazy, back to Sutcliffe to drink beer and giggle about the tenderfoot they had left out on the hillside with his arms raised and his lungs full of air, ready to explode into a frenzy of hooting and windmilling as the cows browsed amiably in his direction.

But just as I was about to let go and feel angry and foolish, I saw something moving on the ridge above the cattle. Three horses were streaking down the hillside, angling off away from the waiting ropers. They were gone out of sight in seconds. The cattle paid them no mind, but I regained some of my ebbing self esteem.

And then three more shapes crested the hill. Through the binoculars I could see that the original plan had gone haywire. When the hazers had come galloping up behind the wild horses, the three mares had bolted for the canyon floor as expected, but the stallion, whether from momentary confusion or from a gallant impulse to help his ladies escape, hesitated. In that long moment one of the Indians made an instinctive split second throw with his lariat. The rope grazed the stallions neck and the horse lunged aside — just far enough to permit the second hazer to sprint between him and his mares.

All this had happened beyond a fold in the hill from where I was watching, but as the two riders began working the wild stallion, they moved into view. First one of the men and then the other sprinted forward to throw his rope. By hell-for-leather horsemanship and shrewd timing they set up a weaving pattern that the mustang could not break through. As one rider plunged down the steep hillside to cut off escape, the other looped his rope at the animal’s head. When he missed his throw he spurred forward to contain the horse while the other made a try. At last, after ten minutes of desperate high-speed maneuvering, one of the riders managed to rope the horse. Twenty minutes later he was side-hobbled in camp, snorting and crow-hopping in disgust.

In the meantime, from their vantage point high in the rocks, the waiting ropers had seen several bands of six and seven horses moving towards the ridges behind them. After resting the horses we set out after them, and again I was stationed at a point of the triangle as a hazer. Two of the riders rode out to circle a high ridge while the ropers waited at its foot.

Late morning passed into early afternoon as I waited under the August sun. An occasional solitary hawk floated past overhead. The hours passed in utter silence.

And then, as I had about decided we had seen the last of those mustangs that day, I spun suddenly around. Behind me I had heard a sharp clattering sound as if an armload of slates had been suddenly dropped. At first I saw nothing. And then, high on the ridgeline far above, I saw a string of horses led by a fleet white mare snaking down the hillside.

For at instant I watched, transfixed by the beauty of their fluid, incredibly rapid descent. Behind them I saw the winded riders struggling after them. I ran forward shouting and waving my arms to drive them back toward Gordon and the others.

Without a break in stride the great white mare veered aside, staring at me in surprise for a split second. And then she dismissed me from her mind with a confident toss of her heavy head. She swerved into a shallow wash leading toward the lake below, and the six trailing horses thundered furiously after her. I took a few clumsy steps as if to follow, not so much thinking I could catch them or stop them, but because they were so almighty beautiful I ached to run along with them. They ran more than five miles before they vanished out of sight.

Turning back in disappointment I saw the cloud of dust they had raised high on the mountains top still hanging in the hot motionless air.

The commotion had warned the other mustangs away, and reluctantly I packed up for the drive back. Gordon and I chatted for a few minutes before I jounced off toward Reno. He and others were staying another day and would be looking for the white mare in the morning.

“But that but that bunch is pretty spooked now,” he said. “Maybe we’ll see them next time out.”

I saw Gordon again later, and we talk for a couple of hours over coffee in the kitchen of the reservation headquarters town of Nixon. He and his brother-in-law run a 85 Head of cattle on reservation land, and they had been out branding the weekend before. But Gordon still works as a heavy equipment operator for the Highway Department too.

He told me about his father, who had lived and worked in the rough, open country all his life. From him Gordon had learned how to work cattle and how to rope and break the wild horses, how to dance the ancient dances and how to speak the old language. His mother remembers with a smile how he practiced as a boy. “He used to rope the chickens in our front yard,” she told me. “He stretched their next until their heads just rolled on the ground.”

Gordon was the first of the reservation kids to go to public high school at Fernley, where are they all go now, and he made the Allstate basketball team three years in a row. Several western universities, Utah State among them, offered him basketball scholarships, but he turned them down in favor of an Indian college in Oklahoma where he studied only briefly.

Back at Nixon he married, settled down in an old house on the Truckee River and began raising a family. When his oldest boy was four, Gordon, his father and his son were in great demand as a dancing troupe. The boy won second prize among dancers from 62 tribes at a meeting in Pendleton Oregon.

“My boy seemed to change away from the old ways as he got older,” Gordon said with regret. “I tried to teach him the cowboy life but he lost interest in it while he was growing up.”

Now that boy is grown and away at refrigeration school at Lawrence Kansas. Gordon is a member of the tribal Council, which is negotiating with developers for design and construction of a multimillion dollar community complex on 7,000 acres of the tribe’s lakeshore land. The planned community will have homes for a population of 15,000, a business district, motels, a luxury resort hotel-casino, a golf course, marina — and jobs.

I asked Gordon if he had caught sight of the white mare since that hot August day more than two years before.

“No,” he said, “I never saw her again.”