Wholesome . . . Delectable . . . Enchanting

Watch Her Movies Here

by David Toll

You might think that a state with so few celebrities to brag about would make a big deal about a movie star who called Nevada home. But Edna Purviance, who starred with Charlie Chaplin in the pictures that elevated him into the first rank among movie stars, is now almost forgotten here. It seems especially strange because she was not only a famous movie star and for ten years Chaplin’s leading lady, and his lover, she was his best and most loyal friend until the day she died.

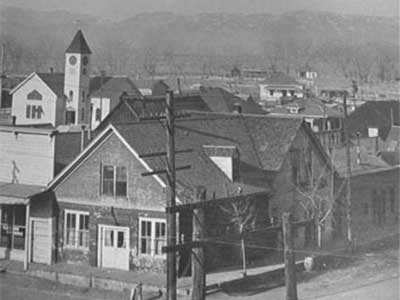

Born in Paradise Valley October 21, 1895, Edna moved as a youngster to Lovelock where she and her sisters Bessie and Myrtle helped their mother keep a boarding house after their parents divorced.

She was locally noted as a pianist, and played a solo at the 1911 high school graduation. In August of that year she was among the entrants in a popularity contest sponsored by the Lovelock Review-Miner, but was not a winner. Her name shows up here and there in the paper, hosting visiting relatives from Winnemucca (the Browns and the Hills), attending parties and performing at the piano at the En Hiver leap year dance in 1912 and at the high school art exhibit in March of the next year.

She graduated from high school herself in 1913, and wasted no time shaking the dust of Lovelock from her heels and getting to San Francisco.

Except for Broadway Street and the railroad tracks, there is nothing left in Lovelock today harking back to the eager young girl who had made the beds and washed the sheets in the boarding house, tending to the needs of the bachelor railroad men and listening to the trains chuffing in and out of town.

Edna’s girlhood friends remembered her as vivacious and attractive, and she found a ready welcome in San Francisco. She shared an apartment with her married sister Bessie, who had a job at the Pan Pacific Exposition as a diving belle. She took a business course, and worked in an office on Market Street while entering into the Bohemian life of the city.

Charlie Chaplin, meanwhile, was a promising young comedian from England who had taken to the music hall stage as a youngster. He made two American tours with a vaudeville show (also featuring the young Stanley Laurel) and landed in Hollywood, at Mack Sennett’s slapstick factory, Keystone Studios. There he made a series of increasingly popular two-reelers. In late 1914 he signed a contract with the Essanay movie company at Niles, California near the southeastern shore of San Francisco Bay.

Early in the following year Charlie and Broncho Billy Anderson drove over to San Francisco in search of a leading lady for their new stock company. This unlikely pair inspected every chorus girl in the city, but failed to find just the right combination of sexy nymphet, mature calm and zany eccentricity that Charlie especially liked.

Then another actor suggested Edna. She wasn’t in show business, but she had a special quality. Perhaps it was her sweet smile, with its hint of mischief. Perhaps it was the duck she sometimes walked on a leash. Whatever it was that made Edna special, Charlie liked it.

In his autobiography he recalled their first meeting at the St. Francis Hotel.

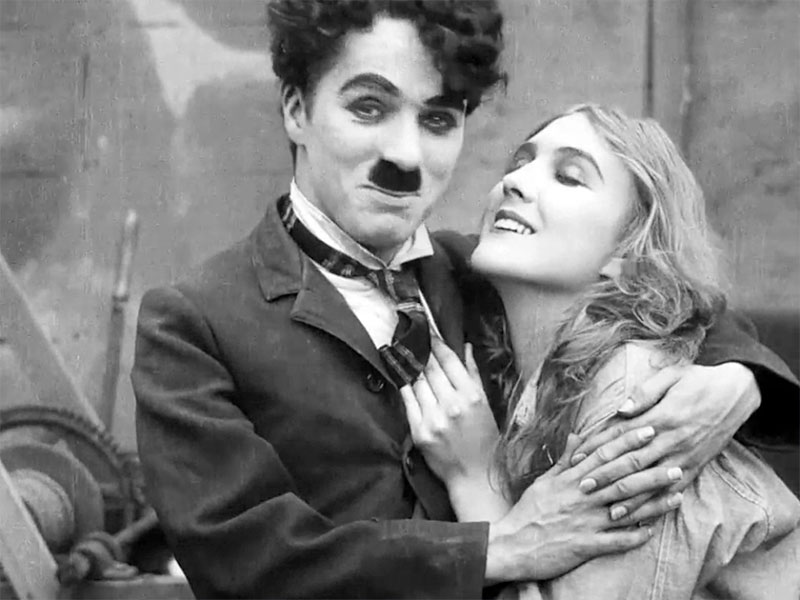

“She was more than pretty, she was beautiful. At the interview she seemed sad and serious. I learned afterward that she was just getting over a love affair. I doubted whether she could act or had any humor, she looked so serious. Nevertheless, with these reservations we engaged her. She would at least be decorative in my comedies.”

The next few days were occupied in preparing the sets for A Night Out, Edna’s first role and Charlie’s first picture for Essanay.

The day before shooting was to begin, one of the Essanay group invited about 20 of the cast and crew to a modest dinner party.

“After supper,”Charlie reminisced, “some played cards while others sat around and talked. We got onto the subject of hypnosis and I bragged about my hypnotic powers. I boasted that within 60 seconds I could hypnotize anyone in the room. I was so convincing that most of the company believed me, but Edna did not.”

Edna laughed at Charlie. “What nonsense!” she said. “No one could hypnotize me.”

“You are just the perfect subject,” Charlie insisted. “I bet you ten dollars that I’ll put you to sleep in sixty seconds.”

“All right,” said Edna. “I’ll bet.”

“Now, if you are not well afterwards, don’t blame me for it! Of course, it will be nothing serious.”

Charlie wanted to frighten her out of the bet, but she would not budge, even when another of the guests told her she was foolish to proceed.

“The bet still goes,” Edna said, in the good old Nevada way.

“Very well,” said Charlie, “I want you to stand with your back firmly against the wall, away from everybody, so that I can get your undivided attention.” As the others watched intently, she obeyed his instructions.

“In sixty seconds you will be completely unconscious,” he said, gazing deeply into her eyes. He held his hands at an odd, electric angle and made two or three dramatic passes while maintaining his piercing stare. He brought his face right up to hers.

“Fake it,” he whispered.

“You will be unconscious,” he hissed. “You are unconscious . . . unconscious!”

She faked it.

As the partiers stared, mouths agape, Edna made two or three staggering steps, then fell swooning into Charlie’s arms. Two of the watching women screamed. “Quick,” he cried, “Someone help me put her on the couch.”

“Although she could have won her argument and proved her point to all present,” he wrote many years later, “she had generously relinquished her triumph for the sake of a good joke. This won her my esteem and affection and convinced me that she had a sense of humor.”

It also convinced him, no doubt, that she could follow his lead, and that she felt rather wonderful in his arms.

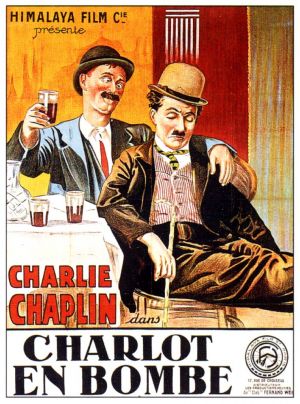

They appeared in 33 films together, beginning in February, 1915, with A Night Out. Most of Edna’s 2-reelers with Charlie are Here. To see Edna’s first appearance on screen, click the poster below —

The Champion was next, with a highly choreographed boxing match as the grand finale. While this tour-de-force sequence was being filmed, Edna dashed him off an affectionate note, and he replied:

“My Own Darling Edna,

“My heart throbbed this morning when I received your sweet letter. It could be nobody else in the world that could have given me so much joy. Your language, your sweet thoughts and the style of your love note only tends to make me crazy over you. I can picture your darling self sitting down and looking up wondering what to say, that pert little mouth and those bewitching eyes so thoughtful. If I only had the power to express my sentiments I would be afraid you’d get vain. . . .”

Edna was his leading lady in The Tramp, in which he firmly established the persona of the little fellow with the ragged clothes and heart of gold. Edna was the farmer’s daughter Charlie rescued from the gang of thugs, and when they shot him, she nursed him back to life. In the bittersweet end, Charlie lost the girl as usual.

Offscreen he got the girl as usual, and during the ten years of their close association that followed, Chaplin’s genius flowered. He moved his troupe back to southern California after making five films at Niles, and finished out his year’s contract by making nine more movies with Edna at Santa Monica. He and Edna were lovers during most of that time, but they did not marry.

“When we first came to work in Los Angeles, Edna rented an apartment near the Athletic Club [where Charlie lived], and almost every night I would bring her there for dinner. We were serious about each other, and at the back of my mind I had the idea we might marry, but I had reservations about Edna. I was uncertain of her, and for that matter uncertain of myself.”

Early in 1915 Charlie went to New York in consequence of his departure from Essanay and a new contract with Mutual. While he was away, Edna made a trip home to Lovelock, and while she was in Nevada she sent Charlie a letter hinting that she was uncertain as well, and that their love affair was beginning to wane:

I really don’t know why you don’t send me some word, she complained. Just one little telegram so unsatisfactory. Even a night letter would be better than nothing. You know ‘Boodie’ you promised faithfully to write. Is your time so taken up that you can’t even think of me. Every night before I go to bed I send out little love thoughts wishing you all the success in the world and counting the minutes until you return. How much longer do you expect to stay. Please, Hon, don’t forget your ‘Modie’ and hurry back. Have been home for over a week and believe me my feet are itching to get back. . . . Have you been true to me? I’m afraid not. Oh, well, do whatever you think is right. I really do trust you to that extent. . . .

Yes, but . . . when Charlie returned from New York he took a room at the Alexandria Hotel. “I had retired early to my room and started undressing, humming to myself one of the latest New York songs. Occasionally I paused, lost in thought, and when I did so a feminine voice from the next room took up the tune where I had left off. Then I took up where she left off, and so it became a joke. Eventually we finished the tune this way. . . .”

“Evidently you have just arrived from New York,” Charlie whispered through the keyhole of the door to the adjoining room.

“I can’t hear you,” came the response.

“Then open the door,” he said.

“I’ll open it a little, but don’t you dare come in.”

“I promise.”

The door opened about four inches, and Charlie found himself gazing at “the most ravishing young blonde . . . all silky negligee . . . the effect was dreamy.”

“Don’t come in or I’ll beat you up!” she said with a sparkling smile. But he did.

“The second night when I came to my room,” he remembered, “she frankly tapped on the door, and once more we embarked nocturnally.” On the third night Charlie was beginning to tire of the game, and on the fourth night he tiptoed into his room and slid into bed alone despite her tapping at the door. On the fifth night she knocked impatiently but he had locked the door; the next morning he checked out.

Obviously Charlie was not averse to “delightful impromptus” as he described this adventure, and by the next year, when he and Edna cranked out eight 2-reelers for Mutual, their romance was clearly fading. Still, they went to all the Red Cross fetes and galas together. “At these affairs Edna would get jealous and had a gentle and insidious way of showing it,” Charlie remembered in his autobiography. When he got too much attention from attractive women, Edna would pretend to faint, and then come to, and ask for Charlie. At a party given by the actress Fanny Ward, Edna “fainted” as before, but this time it wasn’t Charlie she asked for when she revived, but Thomas Meighan, a leading man at Paramount.

Uh-oh.

Fanny told Charlie about it the next day. “I could not believe it,” Charlie remembered. “My pride was hurt; I was outraged.” He was so upset he couldn’t work, and late in the morning he called her. He was going to fume and fuss, but he couldn’t face the finality of the situation. “I understand you called for the wrong man at Fanny Ward’s party. You must be losing your memory!”

“What are you talking about?” Edna said with a laugh. “Who has been telling you all this nonsense?”

“What difference does it make who told me?” Charlie said. “But I think I should mean more to you than that you should openly make a fool of me.”

Edna calmly insisted it was a lie.

“You don’t have to make a pretense with me,” Charlie said with exaggerated indifference. “You’re free to do whatever you like. You’re not married to me. . . .” They talked for over an hour, and Charlie’s indifference evaporated into pleading and imploring. That night she cooked him a supper of ham and eggs and they reconciled.

But three weeks later, when Charlie bumped into Edna at the studio office, she was accompanied by a friend. “You know Tommy Meighan?” she asked.

In that brief moment, he wrote, Edna became a stranger, as if he had met her for the first time.

“Of course,” Charlie replied. “How are you, Tommy?”

Still, Edna continued as Chaplin’s leading lady in two-reelers like Behind the Screen, Easy Street, and The Adventurer, and she continued to play a central role in his life.

In the fall of 1917, for example, she opened an envelope postmarked Bombay, India, (return address: Royal Opera House) to find a letter signed Wheeler Dryden.

Dear Miss Purviance,

Kindly excuse the liberty I take in writing to you, but I am sending you this letter in the hope that you will assist me in my hitherto futile attempts to obtain recognition and acknowledgement from my half-brother Charles Chaplin, for whose Company I believe you are Leading Lady. . . .

In September, 1915, I heard from my father, and in his letter he mentioned that my half-brother, Charlie Chaplin, had been making a great name for himself in Cinema work in America. Well, when I read this you can imagine my surprise, for my father had always kept the secret of my birth unknown to me, and had always evaded any questions on the subject. . . .

Wheeler Dryden went on to explain that he didn’t want anything from Charlie and Sidney except recognition and reunion, but that his letters to them had gone unanswered. “And so, Miss Purviance, I am asking you to intercede with Charlie on my behalf, and let me know what he says. . . .”

Through Edna’s intercession Wheeler Dryden made contact with Charlie and a few years later visited California to be reunited with his mother after nearly 30 years. In 1939 he joined the Chaplin Studio, remaining there until Charlie left the USA for good in 1952.

In 1917 another “impromptu” resulted in his reluctant marriage to 18-year-old Mildred Harris on account of her supposed pregnancy. The morning after the ceremony he went back to work “with a heavy heart.”

Edna had read the morning papers, and as Charlie passed her dressing room she appeared at the door.

“Congratulations,” she said softly.

“Thank you,” Charlie replied, and walked by in embarrassment.

Charlie divorced Mildred Harris in 1920, and in 1921 he made his first clear masterpiece, The Kid, with little Jackie Coogan and 12-year-old Lita Grey.

Lita played the “flirting Angel” in the Tramp’s dream of heaven sequence, and was so successful in the role that Charlie moved Edna out of her fancy dressing room and installed little Lita in it instead. “She clearly was hurt,” Lita recalled later, “and indeed stopped being civil to me; when our paths crossed anywhere on the lot, she would stride regally past, her nose in the air. Yet, peculiarly, she continued, in public at least, to be unfailingly pleasant with Mr. Chaplin.”

Lita described Edna as “a fetching blonde with classically beautiful shoulders and neck and alabaster skin, an extremely able comedienne . . . and at the time of The Kid was winding up her long affair with him, although she didn’t quite know it yet.”

As Lita explained it, Edna had begun drinking. “Not heavily, but enough to displease Charlie, who viewed drinking during working hours as unprofessional and therefore intolerable. More and more often she would approach the camera with her face just a bit pinker, her walk just a bit unsteadier, and Charlie, who never missed a trick, would quietly chide, ‘Watch yourself. It all comes out on film. You can hide these things from the camera for only so long.'”

By then their romantic passions had completely cooled, but their friendship endured. “Although Edna and I were emotionally estranged,” Charlie said, “I was still interested in her career. But looking objectively at Edna, I realized she was growing rather matronly, which would not be suitable for the feminine confection necessary for my future pictures.”

Lita Grey, now aged 16 and about to announce her pregnancy and become Charlie’s second wife, described Edna ungenerously: “Her face was still attractive, but now it was bloated. She had developed a rather ungainly, toes-turned-outward walk that was almost Chaplinesque. She had put on so much weight that Wardrobe had to corset her severely to make her believable as Menjou’s delectable mistress. Her affair with Charlie was long a thing of the past.” Nevertheless, when 18-year-old Lita divorced Charlie in 1926, she named 30-year-old Edna as one of several contributing causes.

As if to finish off her career completely, Edna was suddenly involved in one of the Hollywood scandals that made headlines across the country. She had been the New Year’s Eve guest of an oil magnate named Courtland Dines, and the two of them were still drinking in his hotel room the next day when Mabel Normand came to join the party. When Mabel’s chauffer arrived at Dines’ apartment, an argument erupted, a gun was produced, and the partially clad Dines was shot. The resulting hubbub dealt a death blow to Edna’s career.

Nevertheless her ever-loyal Charlie tried to help her launch a solo career. In 1923 he wrote, directed, and played a bit part in A Woman of Paris in which she starred opposite Adolphe Menjou. The movie was favorably reviewed, but it was Menjou whose talents were praised, not Edna’s. Charlie helped develop yet another role for her, this one in the Josef von Sternberg production, A Woman of the Sea. The movie was never released, and Sternberg said Edna was an unemployable alcoholic.

In 1938 she married Captain Jack Squire, a pilot during the early days of aviation for Pan American Airlines and its subsidiaries, Panagra and Avianca. During his Pan Am years he carried mail, merchandise and passengers over the Andes, into the jungle, many landings on water. Edna loved flying and accompanied Jack on some of his flights over the USA and South America.

She received a small monthly salary from Chaplin’s film company for the rest of her life. She died January 13, 1958, aged 62.

“How could I forget Edna?” Chaplin responded to an interviewer after her death. “She was with me when it all began.”

Indeed, our Edna was the farmer’s daughter who nursed Chaplin’s ‘little fellow’ to life, and his one constant friend through all the years of woman-trouble, talkie-trouble and politics-trouble. It is appropriate that he closed his autobiography by quoting a letter from her, dated November 13th, 1956.

Dear Charlie,

Here I am again with a heart full of thanks, and back in the hospital (Cedars of Lebanon), taking cobalt X-ray treatment on my neck. There cannot be a hell hereafter! . . . Am thankful my innards are O.K., this is purely and simply local, so they say. All of which reminds me of the fellow standing on the corner of Seventh and Broadway tearing up little bits of paper and throwing them to the four winds. A cop comes along and asks him what was the big idea. He answers, “Just keeping the elephants away.” The cop says, “There aren’t any elephants in this district.” The fellow answers: “Well, it works, doesn’t it?” This is my silly for the day, so forgive me.

Hope you and the family are well and enjoying everything you have worked for.

Love always, Edna

Her ashes rest in the West Mausoleum of Grand View cemetery in Glendale California with other long forgotten actors of the silent screen—Lafe McKee and Harry Langdon. In Lovelock there is no monument to Edna anywhere; no Purviance Street, not even an Edna Purviance Film Festival once a year.

Only in Winnemucca, where she spent summers as a girl, is there any memento of Edna and her fabulous career in Nevada. The silk dress she wore so many years ago in The Adventurer is in a display case at the Humboldt Museum, pinned like a butterfly, motionless and faded. Beside it, her photograph smiles brightly out through the glass, her face, once gazed upon raptly by millions, radiant, and serene.