by David W. Toll

History books will tell you that the first American soldier to shed his blood in World War I was a lieutenant in the medical corps, wounded by a shell burst on July 14, 1917 while serving with the British Army near Arras, France.

But the history books are wrong. Three months earlier, on April 12, and only days after Congress voted to enter the war, Cpl T.M. Murphy of the California National Guard was shot through the legs while defending the sacred soil of Elko County.

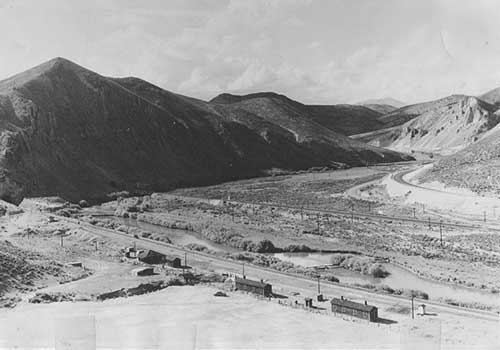

He and his comrades in arms had been called up to active duty immediately upon the declaration of war and assigned to protect bridges, tunnels, piers, power stations and other strategic points against the enemy. Corporal Murphy’s company was assigned to guard the Tonka Tunnel, 12 miles west of Elko on the main line of the Western Pacific Railroad. It was a duty characterized by freezing cold and numbing boredom, broken only by the roaring clamor of the trains rushing through and by the beauty of the star-splashed sky at night.

And so at ten minutes to midnight on the night of the 12th Cpl Murphy was supervising the changing of the guard at the east end of the tunnel when, as the Elko press reported the next day, “one of the soldiers happened to look toward the mouth of the tunnel, and saw a man dart suddenly inside the opening.”

The startled soldier shouted the alarm and Murphy came running. Murphy unlimbered his rifle and, with two of his troopers, advanced into the inky blackness of the tunnel. Their crunching footsteps echoed through the long tube of tunnel as they advanced slowly, bravely and blindly.

Sudden gunshots blazed in the darkness, deafening in the confines of the tunnel, and bullets tore through Murphy’s legs. With a cry he fell to the tracks while his soldiers returned the fire. For a long, chaotic moment bullets flew thick and fast through the tunnel, ricocheting madly off the tunnel walls and whining out into the night.

A hubbub of shouting erupted and Murphy’s men grabbed him up and staggered back the way they had come, struggling to avoid bumping his wounded legs against the rough tunnel walls as they went.

No saboteur emerged from either end of the tunnel, and with the guards on full alert at both closely watched portals, Lt. Weir, the commanding officer, made a brilliant move: he called the Sheriff.

Actually, Elko County Sheriff Harris was a very good man to have on the scene in an emergency, and he arrived at the tunnel mouth at dawn to begin his investigation. When a box of dynamite was found nearby, it seemed certain that a saboteur had been caught in the act of trying to blow up the tunnel. By midmorning half the town of Elko was out at the Tonka Tunnel under the impression that the attacker was still inside.

But a thorough search of the tunnel turned up no trace of any saboteur, just a handful of brass cartridges. When Sheriff Harris came back to town he was shaking his head. “The National Guardsmen did not seem inclined to talk,” he told the correspondent from the Reno Evening Gazette. “I was unable to secure a connected story from them.”

Furthermore, as the Gazette reported, “the dynamite that was found on top of the tunnel apparently was deposited several months ago . . . in a box that was weatherbeaten.”

By the next day the mystery had been cleared up. As Murphy and his men had tiptoed cautiously through the darkness, intent on catching any hint of the fugitive, the sentries at the other end heard them. Convinced that the saboteur was creeping toward them, they had opened fire and mowed down Corporal Murphy. When their fire was returned they snapped off more rounds. Thus the brief but furious battle of Tonka Tunnel.

The wounded Murphy was taken to Elko by train, and recuperated in the local hospital without incident. He was probably back on active duty before his troopers got over their embarrassment.

Three days later the countryside was still aflame with excitement over the shooting when a second and even more mysterious incident occurred. As the Gazette correspondent reported, “The guards at the tunnel west of Elko were fired upon last night by three horsemen employing sniping tactics. They opened fire on the guards at intervals from 9 o’clock till 3 this morning. None of the guards was hit, and there was no damage done. The horsemen escaped around daybreak. . . .”

From then on it was All Quiet on the Northeastern Nevada Front. But you have to wonder who was doing the all-night sniping, and why.

Whoever it was, they can’t dull the luster on the buttons of Cpl T.M. Murphy, the first American casualty of World War One, shot by his buddies at the Battle of Tonka Tunnel, Elko County, Nevada, USA, April 12, 1917.