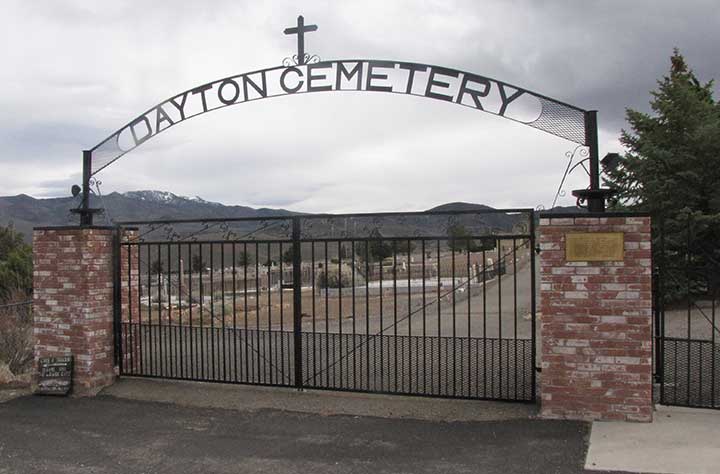

The cemetery in Dayton Nevada is the center of the universe for my family. Dayton and its cemetery is the place our collective identity began. My mother was born in Dayton, her mother was born there and her grandmother came as a small child. She came with her father, mother, brothers and sisters in 1867. Her mother and baby sister both died soon after; the mother and daughter were buried in the cemetery overlooking the town and the valley. Six generations of my family are buried in that primitive, pioneer graveyard.

The cemetery in Dayton Nevada is the center of the universe for my family. Dayton and its cemetery is the place our collective identity began. My mother was born in Dayton, her mother was born there and her grandmother came as a small child. She came with her father, mother, brothers and sisters in 1867. Her mother and baby sister both died soon after; the mother and daughter were buried in the cemetery overlooking the town and the valley. Six generations of my family are buried in that primitive, pioneer graveyard.

My great-grandmother, grandmother, and mother lived in three separate houses during their years in Dayton; only one of these remains. That house is still in our family – it isn’t much of a house, just an old board shack. But, that house and that cemetery represent family and place to us. Since my great-aunt died in 1970 the house has been vacant, except for the occasions when one of us went to Dayton looking for solitude; or one of those unfortunate times when we rented it to strangers. Our Dayton is really an imaginary place, existing more in our imaginations than in reality. Regularly, like Muslims going to Mecca, we make pilgrimages to that imaginary place.

We go there as much as an excuse to tell the stories as to visit the graves. The stories we tell bind us to the people in the graves we visit and to each other. We have stories passed down from generation to generation. Those stories become so real to us that often they become false memories – as if we ourselves had lived them, even though they took place many years before our births. My sister, for example, can remember seeing the blood our mother saw when looking at her mother’s body in 1924. I can see my great-grandmother limping on her wooden leg as she walks up the hill every day carrying a bucket of water for the tree she had planted on her youngest daughter’s grave. The story of Grandma Gates’ grieving and her laborious trip to that grave every day is fundamental to our narrative; it is an essential part of our collective memory. That is very confusing for someone new to the family – boyfriends, girlfriends, husbands, wives, and friends. They struggle trying to sort out which of the stories is from a recent event and which happened a hundred and fifty years ago.

The family members do not draw that line. When we are in Dayton, we live in the past and in our collective memories, not the present day reality. However, in 2011 I got a chance to bring the past into the present. My grandson, Johnny, was on the cross-country team of Sparks High School and in September the team had a race at Dayton High School. The high school is not the one my mother and her mother and her grandmother attended. It is not even in the same part of the town; it is across the river in the new town. That is where the majority of the houses in Dayton are located now.

That new Dayton is a mile or more away from our Dayton. Our house and the cemetery are separate and untouched by this new town. The people who live in the other place rarely venture to our town. And we never visit theirs, except on momentous occasions such as grandsons racing. We have few memories of that side of the river. But we do have a couple and they involve the deserted mining and milling town of Como.

Part of my grandson’s race was on a dirt road that leads into the hills. The road follows a canyon up to Como and the old mill. The mill closed ninety years or more ago and the town and the mill were deserted. However, for a time the mining company maintained its property and its options on the mine and mill. One winter, during the Depression, my mother’s father had a job as custodian of the mill property. He lived there with his second wife. In good weather, they could drive to Dayton and back with ease. However, snow could change that trip dramatically and it did. For a week or two during that winter, they were snowed in and my grandfather’s wife became critically ill. He put on his snowshoes and went to Dayton to get a doctor – a journey of nearly 20 miles. That journey is one of our collective memories, at one time or another, all of us in my family have seen Poppy on his snowshoes coming down from Como to Dayton.

Watching my grandson run on that same road my grandfather had once “run” was a rare treat, a mingling and mixing of life’s narrative. In that race, Johnny mixed with the mist of time in my mind. I could almost see my grandson and my grandfather as they passed going in opposite directions and on very different missions, but both flushed from their efforts. Unfortunately, they were too engrossed in their individual tasks to notice the other. Poppy died in 1959, Johnny wasn’t born until 1994. Their paths have crossed often in the cemetery, but this was their first real meeting and I was the only witness.