The best way to get to Kingston is by way of US 50 to Austin, then west down into the Reese River Valley a couple of miles and then south on the road marked for Big Creek. At Big Creek you turn east and climb into the Toiyabes.

But don’t do it in the family sedan. There are some tough stretches in the heights, and the switchbacks are a special challenge; for these you want a four-wheel drive or an atv.

But don’t do it in the family sedan. There are some tough stretches in the heights, and the switchbacks are a special challenge; for these you want a four-wheel drive or an atv.

The easy way to get there is by driving Old Lonely to Big Smoky on the east side of the Toiyabes, where US 50 is the top bar of a tee with Nevada Highway 376 as its stem leading south. Kingston is about 16 miles from the turnoff, beyond the little cluster of homes in the sagebrush at Gillman Springs.

Access to Kingston is by two inconspicuously marked access roads from Highway 376, Tahoe Road and Kingston Canyon Road, both of which will take you to the third largest community in Lander County (after Battle Mountain and Austin) at the mouth of Kingston Canyon.

Silver discoveries higher up Kingston Canyon in 1862 brought a community called Bunker Hill briefly to life, and mining persisted in a small way into the 1880s when a serious revival took place. The ruins of the Victorine mill at the top of town date to this revival. There have been flurries of interest, but no mining activity currently in the canyon.

Silver discoveries higher up Kingston Canyon in 1862 brought a community called Bunker Hill briefly to life, and mining persisted in a small way into the 1880s when a serious revival took place. The ruins of the Victorine mill at the top of town date to this revival. There have been flurries of interest, but no mining activity currently in the canyon.

Instead there is camping, hiking, fishing and lollygagging under a shade tree going on here now. The road up the canyon is good until it isn’t, but you don’t need to go that far to enjoy yourself.

Instead there is camping, hiking, fishing and lollygagging under a shade tree going on here now. The road up the canyon is good until it isn’t, but you don’t need to go that far to enjoy yourself.

Groves Lake is a favored spot, for obvious reasons, and is seldom crowded.

Groves Lake is a favored spot, for obvious reasons, and is seldom crowded.

Kingston is home to about 80 people in the mostly modest homes scattered around in the sagebrush. The splendid Miles End B&B, is at the center of town. Across from it is a minimally stocked General Store and the Silver Spur Saloon, hours 2 – 9 pm, is just down the road. The one-room Kingston 376 Motel & RV-Park-in-progress occupies Jim Kielhack’s former Sales Office. There’s a volunteer Fire Department, a clinic and a Town Board.

Kingston is as quiet as a ghost town. There are dozens of occupied homes and a small handful of businesses, but nothing moves except an occasional car, seldom more than one at a time anywhere in town, and then it is quiet again..

And there is a ghost, although he doesn’t haunt the place. At the beautiful little pond near the center of things, a cluster of ducks gliding about making eye music, there is a bench with a name on it: Carl Haas. Sit down, enjoy the quiet, the greenery, the water, the reeds, the ducks. Carl isn’t like the Lady in Red at the Mizpah in Tonopah (where he was an enthusiastic visitor) — he didn’t leave any ectoplasm behind and won’t appear suddenly on the bench beside you — but his presence is everywhere you look.

And there is a ghost, although he doesn’t haunt the place. At the beautiful little pond near the center of things, a cluster of ducks gliding about making eye music, there is a bench with a name on it: Carl Haas. Sit down, enjoy the quiet, the greenery, the water, the reeds, the ducks. Carl isn’t like the Lady in Red at the Mizpah in Tonopah (where he was an enthusiastic visitor) — he didn’t leave any ectoplasm behind and won’t appear suddenly on the bench beside you — but his presence is everywhere you look.

Carl owned the RO Ranch 20 miles farther south, and had “created, from what was generally accepted to be a wasteland in Central Nevada, a cattle empire that would ultimately encompass an area larger than some eastern states” as he wrote in his autobiography “Around the World in Eighty Years”. It’s available at the Miles End B&B for $20, all proceeds to the town —

When a California developer gave up his option on the abandoned Schmidtlein Ranch at the mouth of Kingston Canyon, Carl stepped up and bought it.

For the Schmidtlein property Carl had a grand vision. “It should be master-planned to resemble a European Village,” he wrote. “Home sites designed to fit the terrain with deed restrictions, a village site, open spaces. . . .”

His next paragraph begins “The cost would be enormous”.

Indeed.

Converting an abandoned 19th century ranch without electricity into a modern living village in the later 20th century turned out to require constant expenditures: two motels, a restaurant, a water system, intensive research into deeds and water rights, costly title searches, endless efforts to persuade the power company to bring electricity, expensive lawyers and expensive heavy equipment. Plus moving the Miner’s Union Hall up from Tonopah; that’s the General Store. Oh, and the twin-engine Cessna for flying in the pigeons who didn’t have planes of their own.

I visited Kingston during that hectic period, in company with Don Bowers of Nevada Magazine and had the unforgettable experience of hearing Carl Haas recite Edgar Allen Poe’s “Cask of Amontillado”, from memory, start to finish. I am still in awe of that performance. I’ll bet he did it for the pigeons too.

The village-building project came to involve Jim Keilhack who had a real estate license and an enormous fund of optimism, and Don Cirac, Carl’s old pal from Tonopah High who became Kingston’s ambassador to Las Vegas.

And Don’s son Paul —

Kingston! 14 years old, living at Millet 20 miles south.

Get up at 6, feed the horses, milk the fucking cow.

Cook breakfast, pack a lunch (lotsa canned corned beef) THEN go to Kingston to work. Clearing brush, greasin’ equipment, moving 4” sprinklers (effin mosquitos!!!) All the stuff slaves do, and the lifestyle too: slave wages, $5 a day, room & board — cook your own grub from Vigus’s store in Austin (a branch of the fabled Kent’s Market in Fallon).

A workman’s lunch of baloney sandwiches, and cold Campbell’s soup out of the can — Chicken Gumbo was a fave — and hard-boiled eggs, and eating cherries and pears from the trees in the village orchard . . . I learned how to drink brandy in that orchard, taught by an old itinerant jack-mormon brick layer (he did the Washoe County Library, too) and then catching a trout or two by hand to take home for dinner, and putting them on a willow gill stick to stay cold in the crick til work was over.

Friday nights, swimming at Darrough’s, diving for pocket change. An old guy named Cleo Bordine would toss it into the pool so we could then go to Carver’s and maybe get a cheeseburger and shoot a game of 8-ball. Then home on the ass end of Chris Loomis’ Hodaka 100, me holding a flashlight ‘cause the headlamp didn’t work. Ha! Never hit a cow. Petted a few, but never hit one square-on.

Best summer of my life!

Del and Carl were married in the late ’60s. Del’s father Bud Loomis owned the Bundox Restaurant in Reno across the river from what was Norman Biltz’s Holiday Hotel back then. They were both pilots, so the village had an airstrip off to the side, not just for their own convenience, but for the pigeons — prospective customers — flying in to look at property.

an airstrip off to the side, not just for their own convenience, but for the pigeons — prospective customers — flying in to look at property.

They pulled down the old ranch house to make a place for Carl’s big stone house. He called it Valhalla, “a rock house with walls of stone 3½ feet thick, which would withstand the elements for 1,000 years” and it is now the Miles End B&B at the center of town. [note the round window]

The great stone structure is the unexpectedly modern Miles End Bed & Breakfast (and dinner can be arranged too), created and operated by John and Ann Miles over the last 10 years, and now by Chad and Candace Kelly (at left). Chad is a recent graduate Cum Laude of the Edna Purviance College of Manhattans. With its ancient apple orchard in the lawned back yard and the outdoor kitchen and bar, the wood-fired hot tub, the unbroken quiet, the mountains rising up against the star-spangled sky at night, this place is a secret you’ll never keep to yourself.

The great stone structure is the unexpectedly modern Miles End Bed & Breakfast (and dinner can be arranged too), created and operated by John and Ann Miles over the last 10 years, and now by Chad and Candace Kelly (at left). Chad is a recent graduate Cum Laude of the Edna Purviance College of Manhattans. With its ancient apple orchard in the lawned back yard and the outdoor kitchen and bar, the wood-fired hot tub, the unbroken quiet, the mountains rising up against the star-spangled sky at night, this place is a secret you’ll never keep to yourself.

Carl-freakin’-Haas built it, and Del’s brother Chris and I hauled endless truckloads of rock from a quarry at the south side of the crick at the mouth of Kingston, just up the hill from what used to be the “Lodge”.

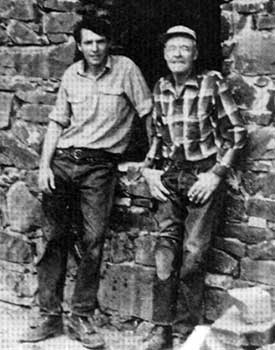

The guy who actually built the rock house was named Jim Sloan (left, in the photo). A good guy, and the first “hippie” to invade Smoky Valley. He was fond of kicking off a meal with:

The guy who actually built the rock house was named Jim Sloan (left, in the photo). A good guy, and the first “hippie” to invade Smoky Valley. He was fond of kicking off a meal with:

“Here’s to you and here’s to me.

And may we never disagree.

But, if, my friend, we ever do,

Well then my friend, to Hell with you.”

He was a man of conviction and a pretty fair painter — his watercolor of Cloverdale hangs in my living room. His wife Greta was a concert violinist, and I got to hear her play Bach for us in the meadow at Cloverdale as we put up the hay with Edsel Ford’s ne’er-do-well kid Tom, who was hiding out in central Nevada dodging divorce papers. We just about killed that poor sap by handing him a pair of T-handled hay-hooks. Haha!

The best story about the rock house is that Carl decided, in his strange, forward-looking way, to set an old steel tank in one of the walls in order to provide “natural” wood-heated hot water for the manse — an automatic wall cracker, due to heat expansion. I believe it’s now a circular window adjacent to the kitchen, on the north wall.

The best story about the rock house is that Carl decided, in his strange, forward-looking way, to set an old steel tank in one of the walls in order to provide “natural” wood-heated hot water for the manse — an automatic wall cracker, due to heat expansion. I believe it’s now a circular window adjacent to the kitchen, on the north wall.

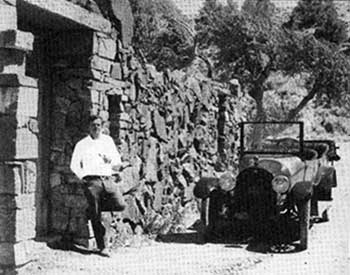

When a pigeon was flying in, he’d buzz us and waggle his wings to let us know he wanted to land, and then it was up to the nearest kid to grab one of the chariots — the 1914 REO touring car or the ‘32 12-banger Lincoln limo — and haul ass down to the airstrip to open the barbed wire gate that kept the cows in.

In three years Carl was broke. Not just because of the development costs, which were humungous, but also because of the “100-year flood” that destroyed one of the motels and many of the homes, and the rise in gasoline prices, and the collapse of the water system, and, and, and. He sold everything he’d accumulated, a lot of it at discounted prices because he needed the cash in a hurry, and spent the money on his dream until it was all gone.

“Kingston Village was a financial failure,” he wrote, “so i felt i might as well walk away and let Kielhack, Cirac  and the other brokers have it.” He paid what debts he could with land and moved from his Valhalla back to the Wine Glass Ranch. Don Cirac moved to Las Vegas with Paul and little Lisa, and launched a barrage of publicity about Kingston, and when a curious pigeon flew in or drove up, there was Jim Kielhack to greet him with a smile.

and the other brokers have it.” He paid what debts he could with land and moved from his Valhalla back to the Wine Glass Ranch. Don Cirac moved to Las Vegas with Paul and little Lisa, and launched a barrage of publicity about Kingston, and when a curious pigeon flew in or drove up, there was Jim Kielhack to greet him with a smile.

All of that is ancient history now (although you can still fly in and out), mostly faded from memory except for those who were there to experience it first-hand. But if you have a taste for digressions, make this one the next time you’re driving US 50. You’ll see the remnants of a dream, an inviting Bed & Breakfast, make a beautiful canyon drive, explore the roadside ruins of the Victorine mill, sit for a quiet moment with Carl at the pond.

Time well spent.