by David Toll

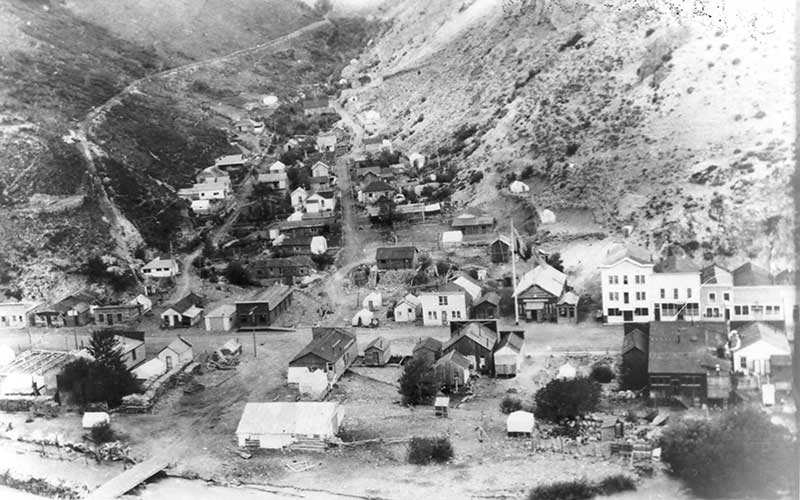

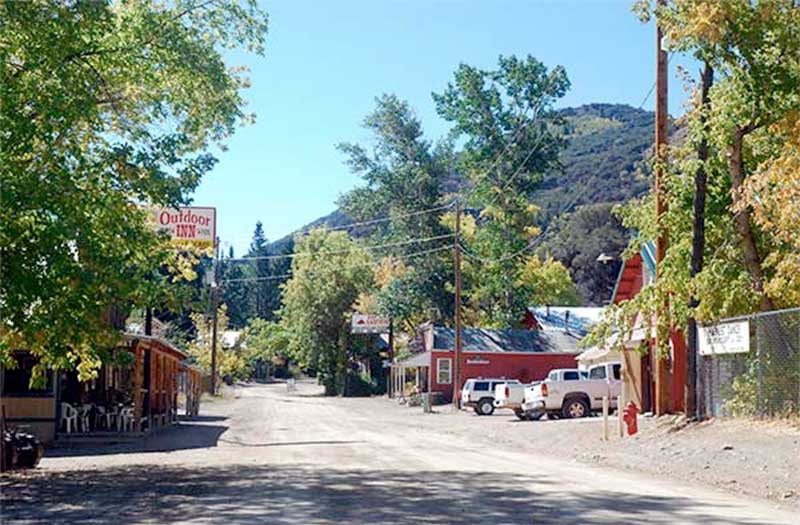

Jarbidge Nevada lies within the narrow steep sided canyon that channels the middle Fork of the Bruneau River, nine miles south of the Idaho border in the northeast corner of Nevada and 6,500 feet above the level of the sea.

Sharply rising walls of rock soar up on either hand to jumbled spurs and crags 2,000 feet and more above the tiny gold rich settlement below. There are many places where the ice never melts; summer nights are cold and the winters are eight months long.

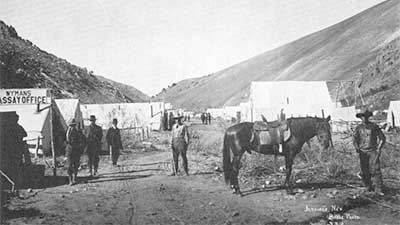

Today the population totals a couple of dozen but in 1916 jarbidge was one of the busiest and most productive mining camps in Nevada.

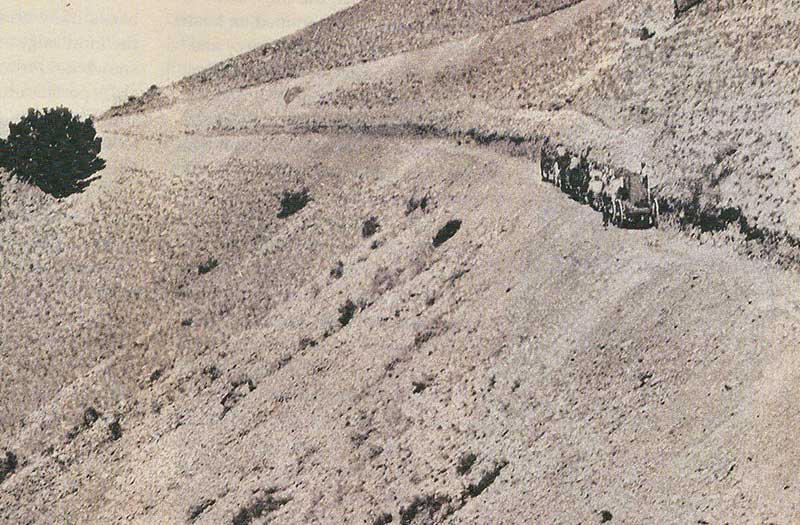

Postmaster Scott Fleming loosened his high starched collar and stared apprehensively into the lacey curtain of falling snow screening the crude buildings across the single street. December had been stormy and snow had fallen steadily since early afternoon of the fifth. By 5 o’clock the stagecoach bringing the mail down from Rogerson Idaho was three hours overdue and Fleming was worried. With three feet of snow choking the higher passes he knew it took all the skill and stamina the driver possessed to hold his horses to the narrow Crippen Grade.

But snow could not discourage the three-days-a-week ritual of greeting that stage and sorting the mail. Among the lonely men who gathered at the Post Office that afternoon was Newt Crumley, proprietor of The Success Saloon. He had come to collect his usual shipment of payday cash from the bank in Rogerson.

Earlier Fleming had watched a string of laden wagons rattle into Jarbidge, their red-faced stiff-limbed drivers sitting high up on the boxes, hurrying their exhausted teams up the narrow canyon street. They had met an outbound train of empty wagons at one of the narrowest points of the grade and been forced to spend the previous night and half of today struggling past one another on the freezing flank of the mountain. Fleming was beginning to think the stagecoach might have met the same wagons before they crested the summit.

At a little after 8 o’clock a miner named Frank Leonard was checking his mail at General Delivery and registered surprise when Fleming told him the mail had not arrived. The outbound drivers had called in from the telephone at Rattlesnake Station at the summit of the Crippen Grade, Leonard told him. They said they had passed the stagecoach on its way down to Jarbidge at mid-afternoon. It should have been in town well before now.

Something was seriously wrong. Immediately Fleming hired Leonard to ride up the Crippen Grade and bring the sack of registered mail back with him if he could retrieve it from the wrecked stage.

When Leonard returned some two hours later, the small post office was filled with concerned men whose buzzing speculation stopped abruptly as he entered. He described a bitterly cold ride through the blinding snow all the way to Rattlesnake Station and no sign of the stagecoach. One of the men suggested a search party and was met with a willing chorus of approval.

“Wait a minute now,” Fleming interrupted. “We know Fred got to the summit and we know he’s not on the road now. Before we go running half-cocked into that blizzard let’s see what else we can find out.” He plucked the telephone receiver from the wall, rotated the crank and asked the operator to ring Rose Dexter, who lived in the last cottage in Lower Town, the straggling collection of shacks and lean-tos across the river.

“Why, yes,” Mrs. Dexter said, the stage had passed her house on the way into town. It had been about 6:30, she remembered, because she heard someone shooting at coyotes and had gone outside to warn them away from the house just as the stage had come around the bend from Rogerson.

She knew Fred Searcy of course. She had called up to him — “but he was bundled up with a heavy lap robe or mail sack across his legs and hadn’t answered,” she told the postmaster. “Probably frozen clear through and in a hurry to get to the barn.”

As Fleming turned toward the curious faces, the door burst open to admit a swirl of snow, along with a frosted giant of a man who stopped in surprise at seeing so many men crowded into the small building. His astonishment increased when he learned that the mail stage had not arrived.

“The hell! I saw the stage three hours ago, not a hundred yards from where I’m standing now!”

The man was one of the teamsters whose arrival Fleming seen earlier. After unloading his wagon he had driven back across the bridge to Lower Town and made camp for the night. As he was unhitching his horses he’d seen the stage approaching and had called out “Hello Kid” to Fred Searcy, wanting to arrange together later. But the stage had hurried. Getting no response he’d finished preparing his animals for the night and then rolled up in one of the wagons for a few hours sleep. He was sure he had seen the stage cross the bridge into town.

Fleming and the others heard him incredulously. With what he and Mrs. Dexter had said, there was no need to search the Grade.

“But how in the hell —” Fleming blurted into the questioning silence, “does a stagecoach with its driver and four horses disappear from a city street?”

Within ten minutes the knot of men from the post office had gathered flashlights and filed out to search between the teamsters’ camp and the bridge without result. They had barely begun covering the Jarbidge street when one of the searchers cried out, carving fat, round slices in the night with his flashlight. Dark shapes and dancing beams converged to illuminate the caller’s boots. The barely discernible wagon track that ran between them doubled back away from town on the old road which forded the river above the bridge.

In the black snow-bent trees at the river’s edge the track was clearer, showing that the wagon had crossed the river to continue on behind Lower Town and then turn off the road to bounce across open ground to the stand of willows. There, nearly hidden, they found the stagecoach.

The horses were shivering in their traces, unable to go on or turn back, and as the men hurries up to them the unhappy animals nickered and rolled their eyes. On the driver’s seat lay Fred Searcy, his body awkwardly twisted and stiff with cold.

“Looks like Fred froze, or passed out first and then froze, and the horses wandered loose until they couldn’t go any further,” suggested Deputy Sheriff Marquardson when he and the Justice of the Peace had been summoned from their beds.

“Well now,” replied Fleming slowly, “that’s about what I thought it first but it doesn’t make sense. When did you ever hear of cold, hungry horses in a blizzard turning themselves off the road within sight of the barn? It doesn’t figure.”

“It figures all right.” Justice Yewell was perched on the side of the wagon. With gentle fingers he had brushed the snow from Searcy’s face and head to reveal a bullet hole above and behind the right ear.

By midnight the little town’s normal winter isolation had been heightened by a cordon of armed men ringing the town with orders to permit no-one to leave without a signed pass. Yewell telephoned Sheriff Harris at the county seat in Elko and asked him to get there right away.

Even today getting to Jarbidge from Elko right away is no easy matter; in 1916 it was impossible. Rogerson in Idaho was the nearest settlement of any consequence and it was 65 wilderness miles away to the north.

Making the trip from Elko in midwinter meant boarding the eastbound train for Ogden, changing trains to head north to Pocatello Idaho, then making the westward leg to Twin Falls and Rogerson. From Rogerson the stage connected with Jarbidge three times a week.

The dawn sky was lumpy with snow clouds as Yewell arrived at the willow grove the following morning accompanied by a half-dozen experienced outdoorsmen. Within a few moments they had confirmed the vague trail of marks in the snow beyond the trees as snow drifted footprints leading towards the river. These they followed slowly and carefully.

Barely 25 yards from the trees one of them, J.B. McCormick, called for help. He got down on his knees and blew the fresh snow from one of the small depressions dappling the surface.

“There, by God! If that’s not a dog’s track I’ll eat it!” After inspecting the print, the others nodded confirmation.

After a moment’s puzzlement Yewell realized that the idea of a man bringing his dog through a blinding blizzard from Idaho to rob the stage was absurd. Obviously, Yewell thought excitedly, the dog had left its tracks while following its master into town.

After a moment’s puzzlement Yewell realized that the idea of a man bringing his dog through a blinding blizzard from Idaho to rob the stage was absurd. Obviously, Yewell thought excitedly, the dog had left its tracks while following its master into town.

What Yewell did next might not have worked everywhere, but in 1916 Jarbidge it worked fine. He stopped the search while men circulated through town picking up all dogs big enough to have made that pawprint and brought them back, snarling and yipping, to compare their prints with the one in the snow. McCormick jabbed one hind leg after another into the crusty snow and carefully examined each print. “It’s that big yellow stray” he said quietly when he was done. The others came over for a look, and once again agreement was unanimous.

At McCormick’s suggestion the other dogs were tied in the willows and the yellow mongrel was released. At first he was delighted at the unaccustomed attention and capered in circles around the men. At length he seemed to understand what was wanted of him and headed for the river, his nose grazing the drifted tracks in the snow. “Keep him in sight but stay off his trail,” McCormick said. “If he stops, you stop too. I’ll handle the dog.”

At the wagon bridge, where the search had begun the night before, the dog stood up on his back legs, forepaws braced against the abutment, and looked back over his shoulder at the men. As McCormick hurried up, the dog dropped back to his feet.

“Mr. Yewell,” McCormick called from beneath the bridge, “you’d better have a look at this.” He reached up into the stringers to drag out a wad of black cloth which he unrolled in the snow to reveal as a long black overcoat, its front spattered and soaked with blood. The dog left the circle of shocked and silent men and padded up a slight rise in the direction of the old road.

“Dog,” said McCormick to himself as he followed the animal with narrowed eyes. “You keep this up and I’ll see you never go hungry again.”

“Dog,” said McCormick to himself as he followed the animal with narrowed eyes. “You keep this up and I’ll see you never go hungry again.”

Beneath the crest of the hill the dog stopped to snuffle and paw at a snow-flocked tangle of brush. When he drew back, his teeth gripped a canvas sack.

“Drop it!” McCormick’s voice echoed flatly in the icy canyon.

The dog released the sack and bounded eight or ten feet away to watch McCormick plunge up the slope and examine his find in the snow. Nearby were a number of ripped envelopes which McCormick gathered up and handed to Yewell.

When the dog resumed his backtracking he led them again to the water’s edge then across the small footbridge into town where he finally lost the trail. When McCormick recognized that the dog’s contribution to the hunt was over he took him home and nearly killed the astonished beast with the biggest steak Jarbidge could supply.

Justice Yewell set men to carefully searching the area between the willows and the river. Back at his office he learned that the sentries on the road out of town had made some discoveries of their own. Deputy Marquardson, who had posted the guards, laid a gray hat on Yewell’s desk. “It was lying in the mud out beyond the Dexter house, he said, “right at the edge of the road.” At the back of the hat there was a powder marked bullet hole.

“Show me,” Yewell said, and the two men walked back toward the wagon bridge until they reached Mrs. Dexter’s house where the road guards were posted.

At daybreak these cold, tired men had searched the road for any sign of traffic out of town during the night. They found nothing to suggest that, but they did find what they thought were the tracks of the mail wagon. And as much to kill their fatigue as for any other reason they had followed the tracks back around the turn toward the grade.

Beyond the bend they had noticed that the tracks ran near the edge of the road for about 120 feet before returning abruptly to the center. The men had gone on another quarter-mile without seeing anything else unusual.

But on their way back, on a little point above the road where the tracks had veered they had found a place where the snow had been considerably disturbed. In the road itself they had found the gray hat, and beside it, faintly visible beneath the fresh layer of snow, a frozen streak of blood that paralleled the wheel track nearly to the bend. Yewell saw for himself the splashed track of Searcy’s lifeblood add the faint trace of the wagon wheel in the snow.

He returned to his office where still another discovery awaited him. Postmaster Fleming, having been given the sack of mail found by the dog, had emptied it on his desk. Among the envelopes that fluttered out was one, ripped open like the rest, that bore the bloody imprint of a human hand. He put it aside for the postal inspectors who were enroute from Spokane and San Francisco.

Meanwhile, more evidence had been found at the bridge: an open sack of coin was discovered in the packet of registered letters directly beneath the bridge, and a few yards downstream a white shirt and a blue bandana, weighted down by stones, had been fished from the water. One of the shirt’s cuffs was stained with blood.

And so matters stood when Yewell’s telephone rang at a little after noon on Thursday, Sheriff Harris’s reedy voice fought through the crackling static on the line to say that he and the District Attorney were in Pocatello.

“Have you come up with anything yet?” he asked.

“I think I know the man who did it,” Yewell said eagerly.

“What does he say?”

“I thought you’d want to be here when we bring him in.”

“No, you’d better put your hands on him right away. If you’re satisfied you had better pick him up.”

When Yewell hung up the phone he called Constable J.C. Hill. They were going to arrest Ben Kuhl.

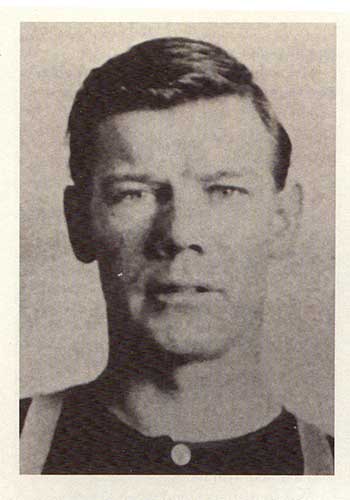

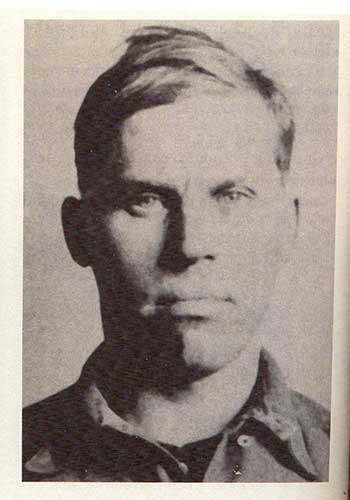

Ben had come to town to work as a cook at the OK Mine but had found the work steadier than he liked. He moved down into town where life was not so tiresome. He was 32 years old and had a tent and enough money to last a week or two, and the opportunist’s yen for an easy lurk.

Ben had come to town to work as a cook at the OK Mine but had found the work steadier than he liked. He moved down into town where life was not so tiresome. He was 32 years old and had a tent and enough money to last a week or two, and the opportunist’s yen for an easy lurk.

Like many mining camps, Jarbidge had a problem with the land titles and Ben had seen a way to capitalize on it. The Hays brothers, Oscar and Ernest, had bought a small parcel of land with a cabin on it next door to the post office. They dragged the cabin off and graded the lot in preparation for putting up a larger building, but when the carpenters showed up for work in the morning they found a small white tent pitched squarely in the center of the lot. Its door flap was peeled back, and in the opening they saw Ben frying his breakfast.

“Get off my property,” Ben said.

The carpenters trotted off for the Hays Brothers.

“What the devil do you think you’re doing here?” cried Oscar Hays as his purposeful strides kicked up puffs of dust.

“I’m eating my breakfast,” said Ben. “What does it look like?”

“Eat your breakfast somewhere else!” roared Ernest, who hurried over to join his brother. “You’ve got no business here.”

“Go home boys,” Ben said airily, “you’re standing on my property.”

“WHAT!?”

“My claim to this ground is as good as yours! As far as I’m con— Uff!”

After Oscar and Ernest had beaten Ben groggy and poured his fried potatoes all over him, they kicked his tent out into the street and sent for Deputy Marquardson to have Ben put in jail.

At the hearing before Justice Yewell Ben had acted as his own attorney, stating that since title was muddy the man from whom the Hays Brothers had bought the land hadn’t actually owned it at all. “Possession,” he said triumphantly, “is nine points of the law.”

“Oh,” Yewell said. “And who is in possession?”

“We are, your Honor,” chorused the Hays Brothers.

“Then I find in your favor on the basis of the precedent cited by the learned Ben Kuhl. I fine Ben $400 dollars with the warning that the matter is hereby resolved.” Ben began a bluster about kangaroo courts but when Yewell tacked on $50 more for contempt he subsided.

On this occasion Yewell asked Ben what he knew about the killing. When Yewell asked him if he owned a gun Ben said he did not, and when Yewell asked him if he owned a long black overcoat Ben said no. “Let’s go have a look at your tent, Ben,” Yewell said.

In the a leather satchel in the satchel was a bone handled .44 with a single empty cartridge under the hammer. When it was gingerly lifted from the freshly laundered shirt on which it rested, a drop of blood was revealed on the white cloth.

“I’ve been framed,” Ben announced.

The minute Sheriff Harris and District Attorney Carville touched their frozen toes to the Jarbidge street on Friday afternoon they were ushered into Yewell’s office for a briefing on the investigation to date. The JP outlined the evidence he had brought to light and gave his interpretation of it.

“Someone,” he said, “slipped out of Jarbidge on Tuesday afternoon with the knowledge that the Success Saloon had a shipment of currency coming in the registered mail sack. The man had walked to the point overlooking the road beyond lower town, and there had waited in the falling snow for the stagecoach. When it had finally rattled past, the killer had taken two or three dancing steps to the lip of the ledge and leapt silently aboard the roof of the coach. Without a word or a wasted motion he had fired his pistol into the back of Fred Searcy’s head.

But the animals had bolted at the sound of the gunshot and veered sharply towards the edge of the road, forcing the killer to grab for the reins with one hand while preventing Searcy’s lolling body from tumbling off the coach with the other. Holding the corpse tightly against him while blood spilled to the roadway from Fred’s open mouth, the murderer had managed to pull the horses back to the center of the road. A short distance beyond the bend into Lower Town, as he had pulled Searcy’s trailing arm from under the seat, he was electrified by a cry from the road.

“Hello Fred! Aren’t you freezing?”

Dimly through 15 feet of falling snow the killer may have made out the figure of Mrs. Dexter on the porch of her small home but he drove past without a word.

Moments later the teamster’s burly baritone sent out his hello. The arm upraised in greeting had seemed indescribably menacing. He urged the horses on — if he stopped now the teamster would come after him.

He heard the hollow drumming of the horses’ hooves on the snow carpeted bridge. Thirty yards ahead were the warm yellow lights of town that would illuminate Fred Searcy’s ruined face, and with a shudder of sudden fear he saw the ribby dog he’d been feeding was regarding him curiously from the road below.

The murderer had yanked the unwilling horses to the side, swinging the wagons onto the old road to splash back across the river and come to rest eventually in the grove of willows. He eased himself from beneath Fred Searcy’s accusing bulk and jumped heavily to the ground. He nearly fell as his rubbery legs buckled under him. The dog made a playful leap.

“Git!” He’d meant to shout, but the quivering release robbed his voice of all authority. The dog danced with pleasure and wagged its tail.

Resigning himself to the dog’s presence, the man had cut open the first class mail sacks and rifled them without finding anything of interest. Taking the locked sack of registered mail he had left the willows, noticing with satisfaction that the snow was falling steadily into his tracks.

Near the river he’d cut open the registered mail and stuffed the envelopes bearing the return address of the bank of Rogerson into his trousers. He was transferring the contents of the coin sack when he became aware of the ghastly sight his blood-drenched clothing presented. He ran cautiously to the wagon bridge and stuffed the coat underneath, in his haste forgetting the coin sack and the packet of letters. He had hurriedly sponged off his hands and face with a bandana before tossing it into his rock-filled shirt and lobbing the bundle into the chuckling black waters. Then, the dog at his heels, he had crossed the footbridge into town and disappeared.

“Ben needed money to pay off the $450 fine, his tent-mate swore that the overcoat was his, the pistol was found in his grip, the shirt pulled from the river was the kind he habitually wore, the pocketknife found in one of the coat pockets was the kind that Ben had been seen to use. And the stray dog had been Ben’s best, if not his only friend in camp.

Silence greeted his recitation and his expression changed from satisfaction to alarm. “What’s wrong?” he asked.

The District Attorney answered with a shake of his head. “Just that everything you’ve turned up is circumstantial. If he keeps on screaming “Frame up” we’re going to have a hard time making a conviction stick. We need something to tie him directly in.”

Kuhl said his so-called friend Ed Beck had stolen his black coat, along with his pocket knife and a dirty shirt, and purposely left them at the murder scene to implicate him.

Yewell, Sheriff Harris, District Attorney Carville and the four postal inspectors then began an intensive investigation which included interviews with dozens of Jarbidge’s residents. Ownership of the revolver was traced to a gambler named Red Bob Irving who claimed to have loaned it to bandy-legged Billy McGraw more than a month before. McGraw admitted having the pistol but swore he had passed it along to another man the day before the killing.

Ben Kuhl? No, he had given it to Ed Beck whom everyone called Cut Lip Swede. The Swede had told him he and a man named Jennings were going deer hunting and didn’t want to be seen carrying a rifle because the season was closed.

When Jennings could be pried away from the card table at Dozier’s saloon he corroborated McGraw’s story and added something else. On the night of the killing, just as Frank Leonard was beginning his fruitless ride to the top of the grade, he had met Beck at the Palm Café. Interested in the outcome of the illicit hunting trip, Jennings had leaned forward “Did you go?” he asked under his breath.

“Go where?” Beck had replied boozily.

“Deer hunting,” whispered Jennings.

Beck froze as the words registered, then he recoiled and his voice boiled up in a whiskey-fragrant whisper that rocked Jennings back. “Shut your mouth you bastard! You dirty son of a bitch, do you want to send a man to the penitentiary?” Nonplussed, Jennings had left the saloon and avoided Beck the rest of the night.

When Beck was questioned he insisted he had borrowed the gun at the insistence of Ben Kuhl. Ben had killed Fred Searcy said and stolen the mail and threatened to kill him if he opened his face. Beck was absolutely satisfied according to the statement he made to the post office inspectors, that Ben had done the job.

Confronted with Beck’s statements a few minutes later, Kuhl made one of his own.”Well yes,” he admitted, Beck had given him the gun but not until after the crime had been committed. Capping a rambling and mostly unsubstantiated account of his movements in Jarbidge the night of the killing he said darkly, “All of this time my suspicions were directed toward the Swede who hinted that he was going to pull off some job.”

The suspicions of everyone else in Jarbidge were directed equally at them both, with a little left over for Billy McGraw. When the three were taken to Elko for trial, sheriff Harris had to disperse an angry crowd to get his prisoners safely out of town.

The trial took place in the Elko County Courthouse the following September, just before winter closed Jarbidge in again. It took three weeks and through it all Ben sat still. He never said a word except to whisper to his lawyer, Edwin Caine. He was supposed to have a wife in Salt Lake City but she never appeared. Ben’s mother came all the way from Indiana, and the newspapers praised the command of her emotions while sneering at Ben’s unnatural calm.

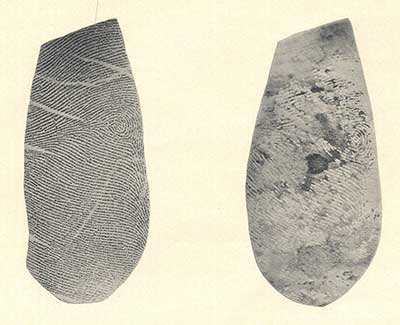

The District Attorney was Ed Carville, later a Nevada governor, and he introduced that chain of circumstantial evidence. He knew trial would not hinge on this, not even on the revolver with the empty cartridge under the hammer. It was when Carville attempted to introduce an enlarged photograph of the bloodstained envelope in evidence that Caine rose up with a flurry of objections, for as one of the postal inspectors had written in a report “it is not hard for a layman to point out the identifying points shown in the enlarged prints made from the envelope and those in the palmprint of Kuhl’s left hand.”

The jury was excluded from the court room while Caine and Carville fought it out. After two days of argument and expert testimony, judge Taber ruled that the prints in the photographic enlargements constituted proper evidence.

“As Mr. King suggested,” Judge Taber said, “the courts should be very careful with the evidence of this kind, and yet it has been observed that there seems to be sometimes too great a difficulty with the courts in adopting the results of science.”

The jury was shown the prints. When Kuhl was sentenced to death Cut-Lip Swede was given a life sentence and the case against Billy McGraw was dropped.

In accordance with the state law at that time, Ben was given the choice of death by hanging or firing squad. He stood before Judge Tabor with the same impassive expression he maintained throughout the trial, and for the first time he let his voice be heard. “I choose to be shot your honor,” he said without feeling. The paper said he was the coolest man in the courtroom and that his mother bore up bravely under the terrible strain and at no time gave way to her feelings.

When Sheriff Harris took Ben aboard the train bound for Carson City and a penitentiary execution yard, he sat him down next to an open window so he could say goodbye to his mother. “Bye-bye mother,” he said and then waited for the train to leave.

His appeal was denied by the Supreme Court of Nevada but in September 1918, as the date of his execution approached, Kuhl confessed to the State Pardons Board that he had killed Searcy. He said that Searcy was going to help fake the holdup, but at the last minute he had refused to go through with it. They had struggled over the gun and Searcy had been killed accidentally.

Ben’s sentence was commuted to life in prison, and for 27 years attended to the chickens at the prison farm, providing fresh eggs for the prison kitchen. Six months after his release he died of pneumonia in Sacramento to close a chapter in American history. No-one again robbed a horse-drawn stage or murdered its driver. Ben Kuhl was the last of his breed.

[…] was discovered in the area, making it one of the last golds in Old West. Jarbridge is also a site last stagecoach robbery In […]