by Richard Bangs

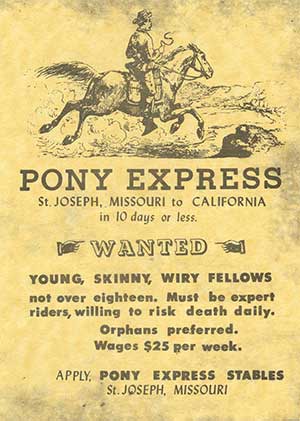

Now we head west on Route 50, the former Pony Express route.  An ad in 1859 read: “WANTED. YOUNG, SKINNY WIRY FELLOWS. Not over eighteen. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. WAGES $25 per week.”

An ad in 1859 read: “WANTED. YOUNG, SKINNY WIRY FELLOWS. Not over eighteen. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. WAGES $25 per week.”

The route is now known as the Loneliest Road in America. In 1986, Life Magazine ran an article about Nevada State Highway 50 entitled “The Loneliest Road.” An AAA spokesperson had described the route through Nevada in these words: “It’s totally empty. There are no points of interest. We don’t recommend it. We warn all motorists not to drive there unless they’re confident of their survival skills.”

So many things about Nevada seem counterintuitive. In that vein, Nevada tourism officials seized on The Loneliest Road pejorative as a marketing slogan, and created signs, stickers and brochures touting such.

They were right, though, as the lonely quality also makes this one of the most sublime corridors I have ever experienced. Much of the time it reminds me of Jerry Bruckheimer’s film intro logo, the boundless straight road and the lightning bolt. After hours of nothingness, it seems we’re driving ever closer to the origins of the earth. A tumbleweed sweeps across the road, whispering some hoary invitation to explore beyond the pavement.

So, we make a short detour down a gravel road into the Ward Charcoal Ovens State Park, featuring a series of six 30’-high beehives built in 1876 to burn locally-harvested timber for use in smelters at a nearby mine. As usual throughout the trip, we are the only ones here, and we step in and out of the giant charcoal kilns, self-stamp our passports, and vanish down the road.

So, we make a short detour down a gravel road into the Ward Charcoal Ovens State Park, featuring a series of six 30’-high beehives built in 1876 to burn locally-harvested timber for use in smelters at a nearby mine. As usual throughout the trip, we are the only ones here, and we step in and out of the giant charcoal kilns, self-stamp our passports, and vanish down the road.

We seem to be navigating a large unfurnished chamber in this next stretch, but it is an occasion with room to think; room to breathe. The interstice is rich here.

In the little community of McGill we stop at the Rexall Drugstore, but it’s not like my neighborhood Walgreens. Stepping inside is like stepping through a time-warp, as though half a century ago the owner went out for a cigarette and never came back.

We’re met by Daniel Braddock, dressed like my grandfather’s pharmacist in bowtie and white paper hat. The shelves are lined with faded products dating back to the 1950s, from the once popular Dippity-do styling gel to Ipana toothpaste.

We’re met by Daniel Braddock, dressed like my grandfather’s pharmacist in bowtie and white paper hat. The shelves are lined with faded products dating back to the 1950s, from the once popular Dippity-do styling gel to Ipana toothpaste.

Daniel, an irenic soul who makes peace with the past, gives an archeological tour down the memory lanes, finally showing off the  space in the back where home remedies and prescriptions were mixed in-store, next to stacks of original invoices, dating back to 1915. Before we leave he dollops double scoops of ice cream at the old fashioned soda fountain, and hands them to us to lick vanilla memories.

space in the back where home remedies and prescriptions were mixed in-store, next to stacks of original invoices, dating back to 1915. Before we leave he dollops double scoops of ice cream at the old fashioned soda fountain, and hands them to us to lick vanilla memories.

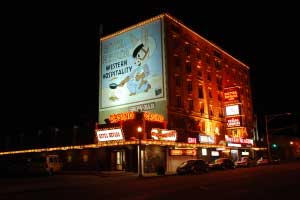

After days of nights in darkness, we pull into the neon wash of Ely. The road has rendered me unfit for glitter, so I sit in the car decompressing for a few minutes before checking into the Hotel Nevada and Gambling Hall, which has its own little walk of fame out front. There are stars in the sidewalk for Pat Nixon and Lyndon Johnson. I ask the receptionist why the stars. He replies they are for celebrities who stayed at the hotel.

“Pat Nixon and Lyndon Johnson. Same room?” I query.

“Pat Nixon and Lyndon Johnson. Same room?” I query.

The receptionist draws a sly smile; silently hands me the key.

We take dinner across the street at the Cell Block Steak House, in which diners sit in jail cells, and are served behind bars by waiters with sheriff badges. The Gunslinger New York steak is to die for. If this is the grub in jails here, I confess to shooting Jim Kelly back in Pioche. Lock me up.

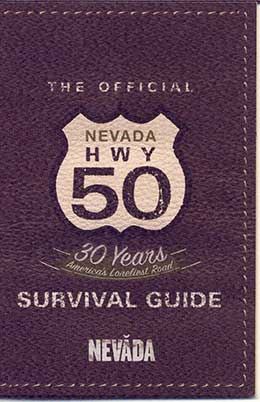

At checkout the morning next I’m handed a little book, “The Official HWY 50 Survival Guide,” which can be stamped at businesses and museums along The Loneliest Road, working towards a state-issued certificate of commemoration. With the day still crisp we head down Route 50 to Eureka, another town defined in ways by what is not there. It was a busy smelting center in the late 19th century, and nicknamed “Pittsburgh of the West.” But, as with most the towns along this route, the mines petered out, and ever since it has been the Big Wait for something to happen next. It today vaunts itself as “The loneliest town on the loneliest road.”

At checkout the morning next I’m handed a little book, “The Official HWY 50 Survival Guide,” which can be stamped at businesses and museums along The Loneliest Road, working towards a state-issued certificate of commemoration. With the day still crisp we head down Route 50 to Eureka, another town defined in ways by what is not there. It was a busy smelting center in the late 19th century, and nicknamed “Pittsburgh of the West.” But, as with most the towns along this route, the mines petered out, and ever since it has been the Big Wait for something to happen next. It today vaunts itself as “The loneliest town on the loneliest road.”

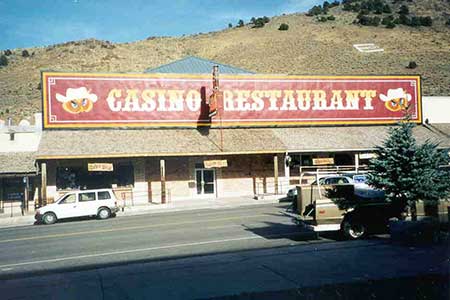

We venture into the Owl Club Bar and Restaurant, noteworthy for its imposing taxidermy, and history of gunfights, dances and rollerball (it was once “The Rinky Dink Roller Rink”). We share lunch with recent owners Eleny Mentaberry and her bar-tending husband Scooter (he calls himself a Precision Carbonation Specialist).

Scooter is part Basque, and there are quite a few in the area, immigrant sheep herders who found a landscape welcoming.  He orders me a picon punch, a concoction that includes grenadine, club soda, a float of brandy, and Amer Picon, a bittersweet aperitif made in France with herbs and burnt orange peel. It’s apparently a Basque-American concoction, without antecedent in the old country, and is now the unofficial state drink. I knock it back. It’s tart, assertive. With the glass empty, I’m reeling… “Like a woman’s breast, one is not enough; three, too many,” says Scooter, as he pushes another in front of me. I pass. I am supposed to drive this next section, but I buckle into the back seat with new admiration for the Basques of Nevada.

He orders me a picon punch, a concoction that includes grenadine, club soda, a float of brandy, and Amer Picon, a bittersweet aperitif made in France with herbs and burnt orange peel. It’s apparently a Basque-American concoction, without antecedent in the old country, and is now the unofficial state drink. I knock it back. It’s tart, assertive. With the glass empty, I’m reeling… “Like a woman’s breast, one is not enough; three, too many,” says Scooter, as he pushes another in front of me. I pass. I am supposed to drive this next section, but I buckle into the back seat with new admiration for the Basques of Nevada.

We glide along like a boat, as if the road is a river, and veer down State Route 376, then down an unpaved spur to the hamlet of Kingston. We park at Zach’s Lucky Spur, a shack of saloon in the shadow of a giant windmill, the only watering hole in a town of about 70 folks. Men’s Health magazine cited it as the “Best Bar in the Middle of Nowhere.” In Nevada, it seems, there is an inverse relationship between the emptiness of the landscape and the quantity of objects inside shops, hotels and bars.

We glide along like a boat, as if the road is a river, and veer down State Route 376, then down an unpaved spur to the hamlet of Kingston. We park at Zach’s Lucky Spur, a shack of saloon in the shadow of a giant windmill, the only watering hole in a town of about 70 folks. Men’s Health magazine cited it as the “Best Bar in the Middle of Nowhere.” In Nevada, it seems, there is an inverse relationship between the emptiness of the landscape and the quantity of objects inside shops, hotels and bars.

Mike Zacharias, the owner, has packed the place with ludic collections, cowboy photos and art, including over 100 spurs, and Rory Calhoun’s vest, which he is sporting as he sips and spins tales. There’s a fantastic story behind every ornament and picture, and it’s easy to believe them all. At one point Zach says “I used to ship bulls for a living…shipped them all over the world. At one time I was the biggest bull-shipper in the world.” I do believe the man.

We’re at about 6,000’ elevation, and after a couple of Icky IPAs (named after Nevada’s official state fossil, the Ichthyosaur) I wobble a few yards down the hill to Miles End B&B (owned by John and Ann Miles, and their dog Zee), a fetching wilderness retreat with a stone lodge (called “Valhalla”), a patch of grass (first green I’ve touched in days), and a wood-burning barrel hot tub, where I soak for a spell under a sky plush with a million points of light. Putting my head back against the oak rim, I feel like I’m falling upwards.

We’re at about 6,000’ elevation, and after a couple of Icky IPAs (named after Nevada’s official state fossil, the Ichthyosaur) I wobble a few yards down the hill to Miles End B&B (owned by John and Ann Miles, and their dog Zee), a fetching wilderness retreat with a stone lodge (called “Valhalla”), a patch of grass (first green I’ve touched in days), and a wood-burning barrel hot tub, where I soak for a spell under a sky plush with a million points of light. Putting my head back against the oak rim, I feel like I’m falling upwards.