Dan Van Zant is determined to preserve and protect

a remarkable piece of Nevada history

Story and photos by Richard Menzies

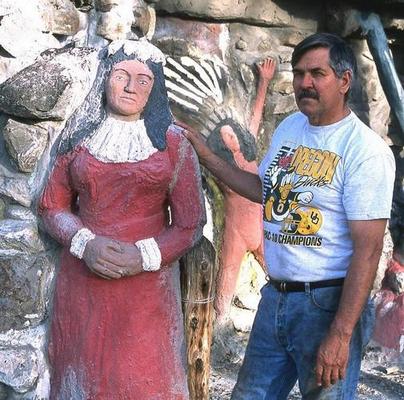

Daniel Van Zant is a middle-aged desk jockey, who, when he’s not developing marketing strategies for an Oregon supermarket chain, can be found scraping bird droppings from concrete statuary in the high desert of Northern Nevada. It’s a strange way to spend one’s vacation, he readily admits. Then again, just about everything around him is a tad strange.

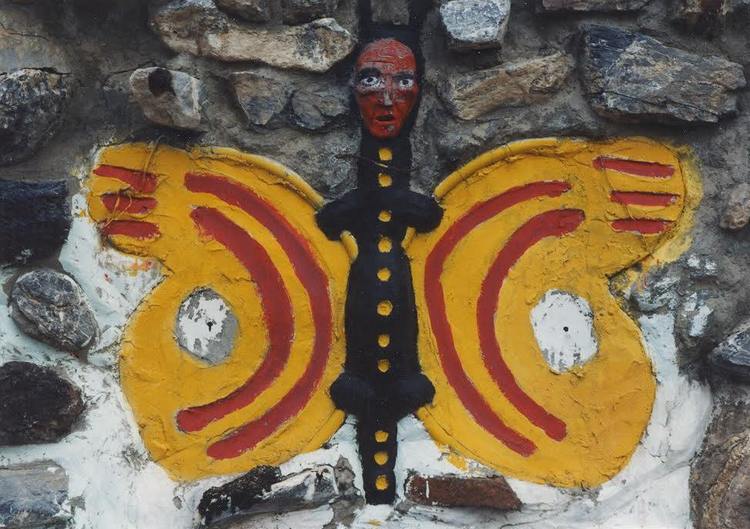

Van Zant is owner and caretaker of Thunder Mountain Monument — five acres jam-packed with exotic folk art and architectural oddities that his late father created over a period of three decades beside Interstate Highway 80 in Pershing County.

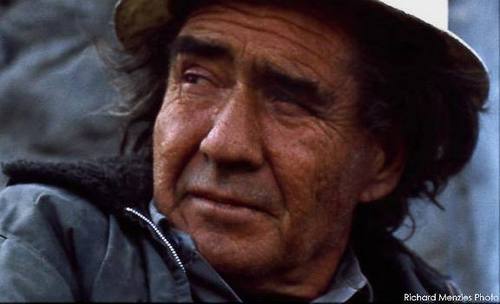

Frank Van Zant, also known as Chief Rolling Mountain Thunder, described his roadside art park variously as a museum, a monument to the American Indian, a retreat for pilgrims aspiring to the “pure and radiant heart.” Many of his neighbors feared Van Zant; others revered him as a spiritual guru.

“He had the charismatic personality that could have made him another Jim Jones,” declares Chief Thunder’s affable eldest son.

Frank Dean Van Zant was born in Okmulgee, Oklahoma on November 11, 1921. Okmulgee is Indian country, and although his surname is Dutch, Van Zant considered himself a full-blooded member of the Creek nation. He left home at the age of 14 and enlisted in the Civilian Conservation Corps, where he picked up pocket change and a variety of skills that would prove useful in later years.

After World War II broke out, Frank enlisted in the Army Air Corps, but had to drop out because flying made him sick to his stomach. So he transferred into the Tank Corps, serving with the 7th Armored Division in seven major campaigns in the European theater.

Years later Frank would tell a reporter from the Los Angeles Times that he had been nearly blown apart “by a German bazooka.” Dan Van Zant can’t confirm the story; he says his father didn’t much like to talk about the war.

“Like a lot of veterans, you’d try to get him to talk, and he’d shut up pretty quick. But it changed him, it definitely changed him. Because in talking to my grandmother, she says that he came back from the war a totally different man.”

Upon returning to civilian life, Frank studied theology for a year and a half, intending to become a man of the cloth. “He was going to be a Methodist minister, and was actually an assistant pastor for awhile,” Dan recalls. “But then he saw the hypocrisy and didn’t want to have anything to do with it, didn’t want to be part of it.”

Van Zant dropped out of divinity school and traded in his Bible for a badge. Law enforcement suited him, and for two decades he served as a sheriff’s deputy in Sutter County, working out of Yuba City, California. In 1960 he ran for the office of sheriff, but narrowly lost. He embarked on a second career as a private investigator, a vocation he pursued until he retired, remarried for the third time and set out for rural Nevada — where he would become reincarnated as Chief Rolling Mountain Thunder.

Why such a radical change of course in midlife? Printed accounts vary. Frank himself offered a variety of explanations, depending upon who was asking the questions and how much he felt like answering them. In one version, he said he had a dream one night that a “great big eagle” swooped down from the sky and told him “this is where I should build his nest.”

Another account has Frank and his young bride Ahtrum heading west in the fall of 1968, looking to find a place in the sun. 130 miles northeast of Reno, near a onetime railroad station named Imlay, his 1946 Chevy pickup truck broke down. He couldn’t get it running again, and so decided to set up camp in the sagebrush. Presently the owner of the property happened along and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

What inspired Frank to start building his Thunder Mountain Monument? According to Dan, when his father was young he had once seen “a bottle house out in the desert, someplace around Death Valley. And he said he just fell in love with it. He said that he wanted to do that someday.”

What inspired Frank to start building his Thunder Mountain Monument? According to Dan, when his father was young he had once seen “a bottle house out in the desert, someplace around Death Valley. And he said he just fell in love with it. He said that he wanted to do that someday.”

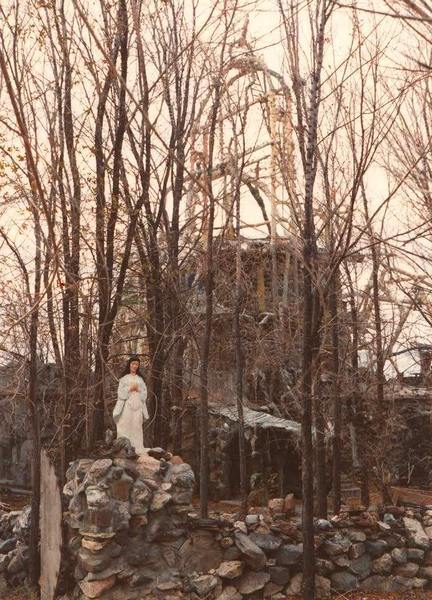

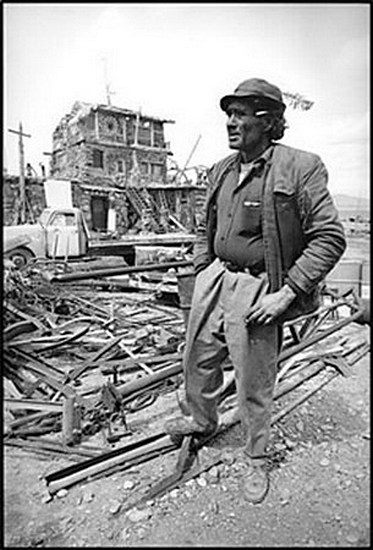

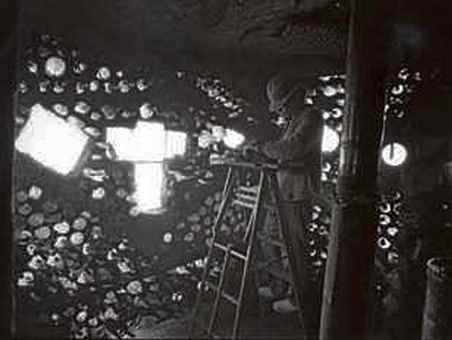

Van Zant’s three-story monument started out as a one-room travel trailer, which he gradually rocked over until it came to resemble Barney Rubble’s stone-age bungalow. As materials became available, he added corridors and stairways leading to upstairs bedrooms formed of daub-and-bottle walls and slate ceilings. He turned automobile windshields into picture windows, scrap iron and galvanized pipe into rebar, concrete and chicken wire into ornamental statuary. Virtually every square foot of the monument’s exterior is covered with friezes and bas-relief tableaux depicting historic massacres and/or bureaucratic betrayals visited upon the American Indian. The roof is adorned with still more statues and multiple arches, the tallest of which soars fifty feet into the sky. At the very top is perched a carved wooden eagle, which only recently was restored to perpendicular by a courageous local, Jim Lacey.

Even as the monument was under construction, it was joined by various Krazy Kat outbuildings, including the roundhouse and the hostel house, a 40×60-foot work shed, an underground hut, guest cabins and a quixotic children’s playground straight out of a Tim Burton movie. Soon Thunder Mountain became a popular hangout for hippie artisans and counterculture characters — much on the order of the Meta Tantay commune established in East Carlin by the Cherokee Medicine Man John “Rolling Thunder” Pope. During the late Sixties and early Seventies, interest in living the Indian way ran high, and there were more dropped-out disciples and vision questers roaming about Northern Nevada than just one Chief Thunder could accommodate.

Was transcendental medication part of the Imlay scene? Dan Van Zant insists that his father was opposed to mind-altering drugs and wouldn’t permit their use on the grounds. Instead, the chief architect of Thunder Mountain appeared to be fueled by tobacco and caffeine, and driven by forces even his closest of kin couldn’t fathom.

“Oh, yeah, I thought the old man had slipped a cog,” says Dan Van Zant. “That’s why I questioned what he was doing, why he was doing this — wanting to start all over with raising a family and building a monument in the middle of nowhere. But that was what he wanted to do. And he didn’t want to live alone. He wasn’t the type of personality that could not be around people. I think he enjoyed being around people; he could never be a hermit.”

As the 1970’s drew to a close and the political pendulum began to swing to the right, Thunder Mountain fell into disrepair. In 1983 the three-story hostel house burned to the ground; then the underground hut caved in. By and by the last of the hippie artisans drifted back to suburbia. Finally Frank’s wife left him, taking with her the couple’s three young children. The Thunder family patriarch found himself alone, with no one for company save concrete likenesses of Quetzalcoatl, Standing Bear, Sarah Winnemucca, and his beloved son Sid, who had died at the age of 19. His health failing — the result of a lifelong addiction to cigarettes — Van Zant became increasingly depressed. On January 5th, 1989, after penning a farewell note to his son Dan, the chief lay down on a sofa in the roundhouse and put a bullet through his brain.

As the 1970’s drew to a close and the political pendulum began to swing to the right, Thunder Mountain fell into disrepair. In 1983 the three-story hostel house burned to the ground; then the underground hut caved in. By and by the last of the hippie artisans drifted back to suburbia. Finally Frank’s wife left him, taking with her the couple’s three young children. The Thunder family patriarch found himself alone, with no one for company save concrete likenesses of Quetzalcoatl, Standing Bear, Sarah Winnemucca, and his beloved son Sid, who had died at the age of 19. His health failing — the result of a lifelong addiction to cigarettes — Van Zant became increasingly depressed. On January 5th, 1989, after penning a farewell note to his son Dan, the chief lay down on a sofa in the roundhouse and put a bullet through his brain.

Thunder Mountain became deserted, although curious visitors continued to trickle in off the freeway — as did more than a few vandals. Nocturnal thrill seekers would belay themselves down the chimney into the monument’s main chamber, where they would drink beer and tell ghost stories. Water was also invading the structure, thanks to a porous roof. Piece by piece, Frank Van Zant’s monument to the American Indian was going the way of the buffalo and the passenger pigeon.

Although his father had willed him the property in his suicide note, it took awhile for Dan Van Zant to gain legal custody. His next goal was to somehow preserve and protect the place — but how?

Although his father had willed him the property in his suicide note, it took awhile for Dan Van Zant to gain legal custody. His next goal was to somehow preserve and protect the place — but how?

“My first thoughts were that I would just donate it to the state of Nevada,” he says. “They could make it a state park. And a person who was director of the state parks division actually came out, met with me, and he walked the property. He basically was pretty candid; he just said, ‘This place is a mess.’”

Dan Van Zant and his wife Margie have since hauled away a couple hundred pickup loads of trash — what his father would have called building material.

That was what he used to build with,” says Dan. “He had it scattered around so he could see what he had.”

Today the bone yard is confined to just a 400-square foot area against the west wall of the burned-down hostel house, and Dan estimates there’s enough used lumber in the pile to build a visitor’s center. He’d also like to install an underground irrigation system so he can keep the shade trees alive and green up the grounds. “Green it up, put in some park benches, picnic tables, and make it a little more appealing to the general public.”

All of which will take time, not to mention money. For that, the propreitor of Thunder Mountain relies solely on the kindness of strangers–one of whom, after taking a tour of the grounds, mailed Dan a check for $20,000. A large chunk of the cash went toward replacing the leaky roof; a smaller chunk toward casting a bronze plaque honoring the munificent benefactor.

Dan regards the twenty thousand dollar contribution as nothing short of a miracle — one of many said to have have occurred upon the patch of land his father held sacred. Once, back when the monument was fully occupied by improvident hippie artisans, there arose a food shortage. The story goes that the chief did an Indian dance and offered up a prayer. Later that same day, a semi-trailer truck loaded with frozen food crashed on the highway. The driver, grateful to be alive, told the group to help themselves to the spilled groceries.

Dan regards the twenty thousand dollar contribution as nothing short of a miracle — one of many said to have have occurred upon the patch of land his father held sacred. Once, back when the monument was fully occupied by improvident hippie artisans, there arose a food shortage. The story goes that the chief did an Indian dance and offered up a prayer. Later that same day, a semi-trailer truck loaded with frozen food crashed on the highway. The driver, grateful to be alive, told the group to help themselves to the spilled groceries.

Frank Van Zant never planned too far ahead, preferring to rely on divine providence. His son Dan, confident that the Great Spirit still abides at Thunder Mountain, is determined to see that his father’s life’s work will not soon fade away.