One of the most memorable episodes in “Roughing It” recounts how young Sam Clemens hiked up to Lake Tahoe from Carson City.

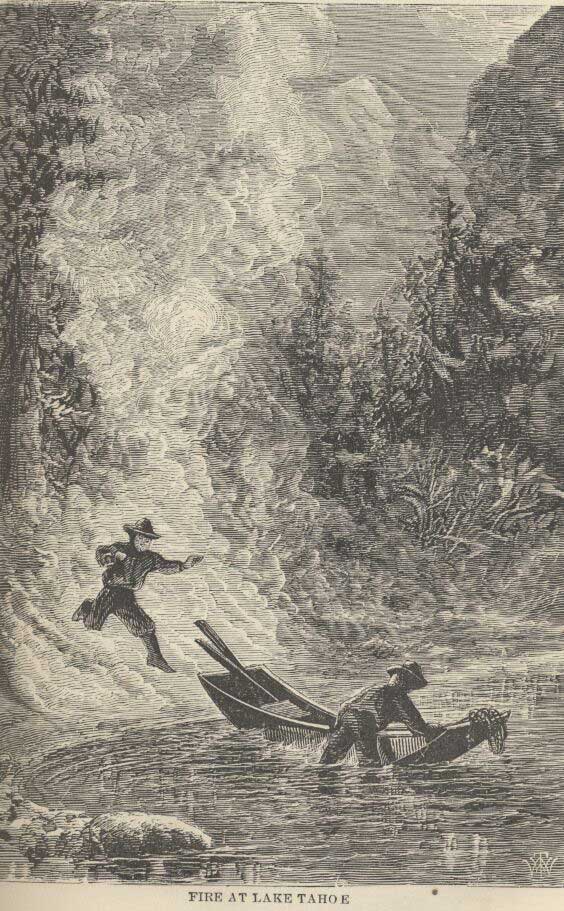

He tells how he and his companion staked a timber claim and accidentally set the forest on fire. The two escaped with their lives by rowing their skiff out into the lake and waiting for the flames to die down.

But for all its admirable qualities as prose that flirted now and then with poetry, Twain’s description of his Tahoe excursions — he actually made two visits to the lake, but conflated them into one in his book — lacked geographical specificity, and scholars ever since have wondered just where it was that he had made camp. Speculation placed the camp at several different places on both the Nevada and California sides of the lake. But it was only recently that a group of curious Twainiacs figured out exactly where it was.

Lead investigator in this effort was Bob Stewart, who had already become conversant with Clemens’ Nevada adventures from the research he did for his book “Aurora, Nevada’s Ghost City of the Dawn”. He was assisted by a modern version of The Baker Street Irregulars who helped piece the tale together.

There are four parts to this long story, linked in order below. Use them or just read it straight through.

Chapters XXII and XXIII in Roughing It by Mark Twain.

Locating Clemens Cove by Bob Stewart.

Finding the Faro Table by Larry Schmidt

Making it Official by McAvoy Layne

Making it Unofficial by David Toll

– – – – – – – _/ _/ _/ _/ – – – – – – –

It was the end of August, and the skies were cloudless and the weather superb. In two or three weeks I had grown wonderfully fascinated with the curious new country and concluded to put off my return to “the States” awhile. I had grown well accustomed to wearing a damaged slouch hat, blue woolen shirt, and pants crammed into boot-tops, and gloried in the absence of coat, vest and braces. I felt rowdyish and “bully,” (as the historian Josephus phrases it, in his fine chapter upon the destruction of the Temple). It seemed to me that nothing could be so fine and so romantic.

I had become an officer of the government, but that was for mere sublimity. The office was an unique sinecure. I had nothing to do and no salary. I was private Secretary to his majesty the Secretary and there was not yet writing enough for two of us. So Johnny K—— and I devoted our time to amusement. He was the young son of an Ohio nabob and was out there for recreation. He got it. We had heard a world of talk about the marvellous beauty of Lake Tahoe, and finally curiosity drove us thither to see it. Three or four members of the Brigade had been there and located some timber lands on its shores and stored up a quantity of provisions in their camp.

We strapped a couple of blankets on our shoulders and took an axe apiece and started—for we intended to take up a wood ranch or so ourselves and become wealthy. We were on foot. The reader will find it advantageous to go horseback. We were told that the distance was eleven miles. We tramped a long time on level ground, and then toiled laboriously up a mountain about a thousand miles high and looked over. No lake there. We descended on the other side, crossed the valley and toiled up another mountain three or four thousand miles high, apparently, and looked over again. No lake yet. We sat down tired and perspiring, and hired a couple of Chinamen to curse those people who had beguiled us.

Thus refreshed, we presently resumed the march with renewed vigor and determination. We plodded on, two or three hours longer, and at last the Lake burst upon us—a noble sheet of blue water lifted six thousand three hundred feet above the level of the sea, and walled in by a rim of snow-clad mountain peaks that towered aloft full three thousand feet higher still! It was a vast oval, and one would have to use up eighty or a hundred good miles in traveling around it. As it lay there with the shadows of the mountains brilliantly photographed upon its still surface I thought it must surely be the fairest picture the whole earth affords.

We found the small skiff belonging to the Brigade boys, and without loss of time set out across a deep bend of the lake toward the landmarks that signified the locality of the camp. I got Johnny to row—not because I mind exertion myself, but because it makes me sick to ride backwards when I am at work. But I steered. A three-mile pull brought us to the camp just as the night fell, and we stepped ashore very tired and wolfishly hungry. In a “cache” among the rocks we found the provisions and the cooking utensils, and then, all fatigued as I was, I sat down on a boulder and superintended while Johnny gathered wood and cooked supper. Many a man who had gone through what I had, would have wanted to rest.

We found the small skiff belonging to the Brigade boys, and without loss of time set out across a deep bend of the lake toward the landmarks that signified the locality of the camp. I got Johnny to row—not because I mind exertion myself, but because it makes me sick to ride backwards when I am at work. But I steered. A three-mile pull brought us to the camp just as the night fell, and we stepped ashore very tired and wolfishly hungry. In a “cache” among the rocks we found the provisions and the cooking utensils, and then, all fatigued as I was, I sat down on a boulder and superintended while Johnny gathered wood and cooked supper. Many a man who had gone through what I had, would have wanted to rest.

It was a delicious supper—hot bread, fried bacon, and black coffee. It was a delicious solitude we were in, too. Three miles away was a saw-mill and some workmen, but there were not fifteen other human beings throughout the wide circumference of the lake. As the darkness closed down and the stars came out and spangled the great mirror with jewels, we smoked meditatively in the solemn hush and forgot our troubles and our pains. In due time we spread our blankets in the warm sand between two large boulders and soon feel asleep, careless of the procession of ants that passed in through rents in our clothing and explored our persons. Nothing could disturb the sleep that fettered us, for it had been fairly earned, and if our consciences had any sins on them they had to adjourn court for that night, any way. The wind rose just as we were losing consciousness, and we were lulled to sleep by the beating of the surf upon the shore.

It is always very cold on that lake shore in the night, but we had plenty of blankets and were warm enough. We never moved a muscle all night, but waked at early dawn in the original positions, and got up at once, thoroughly refreshed, free from soreness, and brim full of friskiness. There is no end of wholesome medicine in such an experience. That morning we could have whipped ten such people as we were the day before—sick ones at any rate. But the world is slow, and people will go to “water cures” and “movement cures” and to foreign lands for health. Three months of camp life on Lake Tahoe would restore an Egyptian mummy to his pristine vigor, and give him an appetite like an alligator. I do not mean the oldest and driest mummies, of course, but the fresher ones.

The air up there in the clouds is very pure and fine, bracing and delicious. And why shouldn’t it be?—it is the same the angels breathe. I think that hardly any amount of fatigue can be gathered together that a man cannot sleep off in one night on the sand by its side. Not under a roof, but under the sky; it seldom or never rains there in the summer time.

The air up there in the clouds is very pure and fine, bracing and delicious. And why shouldn’t it be?—it is the same the angels breathe. I think that hardly any amount of fatigue can be gathered together that a man cannot sleep off in one night on the sand by its side. Not under a roof, but under the sky; it seldom or never rains there in the summer time.

I know a man who went there to die. But he made a failure of it. He was a skeleton when he came, and could barely stand. He had no appetite, and did nothing but read tracts and reflect on the future. Three months later he was sleeping out of doors regularly, eating all he could hold, three times a day, and chasing game over mountains three thousand feet high for recreation. And he was a skeleton no longer, but weighed part of a ton. This is no fancy sketch, but the truth. His disease was consumption. I confidently commend his experience to other skeletons.

I know a man who went there to die. But he made a failure of it. He was a skeleton when he came, and could barely stand. He had no appetite, and did nothing but read tracts and reflect on the future. Three months later he was sleeping out of doors regularly, eating all he could hold, three times a day, and chasing game over mountains three thousand feet high for recreation. And he was a skeleton no longer, but weighed part of a ton. This is no fancy sketch, but the truth. His disease was consumption. I confidently commend his experience to other skeletons.

I superintended again, and as soon as we had eaten breakfast we got in the boat and skirted along the lake shore about three miles and disembarked. We liked the appearance of the place, and so we claimed some three hundred acres of it and stuck our “notices” on a tree. It was yellow pine timber land—a dense forest of trees a hundred feet high and from one to five feet through at the butt. It was necessary to fence our property or we could not hold it. That is to say, it was necessary to cut down trees here and there and make them fall in such a way as to form a sort of enclosure (with pretty wide gaps in it). We cut down three trees apiece, and found it such heart-breaking work that we decided to “rest our case” on those; if they held the property, well and good; if they didn’t, let the property spill out through the gaps and go; it was no use to work ourselves to death merely to save a few acres of land.

Next day we came back to build a house—for a house was also necessary,in order to hold the property. We decided to build a substantial log-house and excite the envy of the Brigade boys; but by the time we had cut and trimmed the first log it seemed unnecessary to be so elaborate, and so we concluded to build it of saplings. However, two saplings, duly cut and trimmed, compelled recognition of the fact that a still modester architecture would satisfy the law, and so we concluded to build a “brush” house.  We devoted the next day to this work, but we did so much “sitting around” and discussing, that by the middle of the afternoon we had achieved only a half-way sort of affair which one of us had to watch while the other cut brush, lest if both turned our backs we might not be able to find it again, it had such a strong family resemblance to the surrounding vegetation. But we were satisfied with it.

We devoted the next day to this work, but we did so much “sitting around” and discussing, that by the middle of the afternoon we had achieved only a half-way sort of affair which one of us had to watch while the other cut brush, lest if both turned our backs we might not be able to find it again, it had such a strong family resemblance to the surrounding vegetation. But we were satisfied with it.

We were land owners now, duly seized and possessed, and within the protection of the law. Therefore we decided to take up our residence on our own domain and enjoy that large sense of independence which only such an experience can bring. Late the next afternoon, after a good long rest, we sailed away from the Brigade camp with all the provisions and cooking utensils we could carry off—borrow is the more accurate word —and just as the night was falling we beached the boat at our own landing.

If there is any life that is happier than the life we led on our timber ranch for the next two or three weeks, it must be a sort of life which I have not read of in books or experienced in person. We did not see a human being but ourselves during the time, or hear any sounds but those that were made by the wind and the waves, the sighing of the pines, and now and then the far-off thunder of an avalanche. The forest about us was dense and cool, the sky above us was cloudless and brilliant with sunshine, the broad lake before us was glassy and clear, or rippled and breezy, or black and storm-tossed, according to Nature’s mood; and its circling border of mountain domes, clothed with forests, scarred with land-slides, cloven by canons and valleys, and helmeted with glittering snow, fitly framed and finished the noble picture. The view was always fascinating, bewitching, entrancing. The eye was never tired of gazing, night or day, in calm or storm; it suffered but one grief, and that was that it could not look always, but must close sometimes in sleep.

We slept in the sand close to the water’s edge, between two protecting boulders, which took care of the stormy night-winds for us. We never took any paregoric to make us sleep. At the first break of dawn we were always up and running foot-races to tone down excess of physical vigor and exuberance of spirits. That is, Johnny was—but I held his hat. While smoking the pipe of peace after breakfast we watched the sentinel peaks put on the glory of the sun, and followed the conquering light as it swept down among the shadows, and set the captive crags and forests free. We watched the tinted pictures grow and brighten upon the water till every little detail of forest, precipice and pinnacle was wrought in and finished, and the miracle of the enchanter complete. Then to “business.”

That is, drifting around in the boat. We were on the north shore. There, the rocks on the bottom are sometimes gray, sometimes white. This gives the marvelous transparency of the water a fuller advantage than it has elsewhere on the lake. We usually pushed out a hundred yards or so from shore, and then lay down on the thwarts, in the sun, and let the boat drift by the hour whither it would. We seldom talked. It interrupted the Sabbath stillness, and marred the dreams the luxurious rest and indolence brought. The shore all along was indented with deep, curved bays and coves, bordered by narrow sand-beaches; and where the sand ended, the steep mountain-sides rose right up aloft into space—rose up like a vast wall a little out of the perpendicular, and thickly wooded with tall pines.

That is, drifting around in the boat. We were on the north shore. There, the rocks on the bottom are sometimes gray, sometimes white. This gives the marvelous transparency of the water a fuller advantage than it has elsewhere on the lake. We usually pushed out a hundred yards or so from shore, and then lay down on the thwarts, in the sun, and let the boat drift by the hour whither it would. We seldom talked. It interrupted the Sabbath stillness, and marred the dreams the luxurious rest and indolence brought. The shore all along was indented with deep, curved bays and coves, bordered by narrow sand-beaches; and where the sand ended, the steep mountain-sides rose right up aloft into space—rose up like a vast wall a little out of the perpendicular, and thickly wooded with tall pines.

So singularly clear was the water, that where it was only twenty or thirty feet deep the bottom was so perfectly distinct that the boat seemed floating in the air! Yes, where it was even eighty feet deep. Every little pebble was distinct, every speckled trout, every hand’s-breadth of sand. Often, as we lay on our faces, a granite boulder, as large as a village church, would start out of the bottom apparently, and seem climbing up rapidly to the surface, till presently it threatened to touch our faces, and we could not resist the impulse to seize an oar and avert the danger. But the boat would float on, and the boulder descend again, and then we could see that when we had been exactly above it, it must still have been twenty or thirty feet below the surface. Down through the transparency of these great depths, the water was not merely transparent, but dazzlingly, brilliantly so. All objects seen through it had a bright, strong vividness, not only of outline, but of every minute detail, which they would not have had when seen simply through the same depth of atmosphere. So empty and airy did all spaces seem below us, and so strong was the sense of floating high aloft in mid-nothingness, that we called these boat-excursions “balloon-voyages.”

We fished a good deal, but we did not average one fish a week. We could see trout by the thousand winging about in the emptiness under us, or sleeping in shoals on the bottom, but they would not bite—they could see the line too plainly, perhaps. We frequently selected the trout we wanted, and rested the bait patiently and persistently on the end of his nose at a depth of eighty feet, but he would only shake it off with an annoyed manner, and shift his position.

We bathed occasionally, but the water was rather chilly, for all it looked so sunny. Sometimes we rowed out to the “blue water,” a mile or two from shore. It was as dead blue as indigo there, because of the immense depth. By official measurement the lake in its centre is one thousand five hundred and twenty-five feet deep!

Sometimes, on lazy afternoons, we lolled on the sand in camp, and smoked pipes and read some old well-worn novels. At night, by the camp-fire, we played euchre and seven-up to strengthen the mind—and played them with cards so greasy and defaced that only a whole summer’s acquaintance with them could enable the student to tell the ace of clubs from the jack of diamonds.

We never slept in our “house.” It never recurred to us, for one thing; and besides, it was built to hold the ground, and that was enough. We did not wish to strain it.

By and by our provisions began to run short, and we went back to the old camp and laid in a new supply. We were gone all day, and reached home again about night-fall, pretty tired and hungry. While Johnny was carrying the main bulk of the provisions up to our “house” for future use, I took the loaf of bread, some slices of bacon, and the coffee-pot, ashore, set them down by a tree, lit a fire, and went back to the boat to get the frying-pan. While I was at this, I heard a shout from Johnny, and looking up I saw that my fire was galloping all over the premises! Johnny was on the other side of it. He had to run through the flames to get to the lake shore, and then we stood helpless and watched the devastation.

The ground was deeply carpeted with dry pine-needles, and the fire touched them off as if they were gunpowder. It was wonderful to see with what fierce speed the tall sheet of flame traveled! My coffee-pot was gone, and everything with it. In a minute and a half the fire seized upon a dense growth of dry manzanita chapparal six or eight feet high, and then the roaring and popping and crackling was something terrific. We were driven to the boat by the intense heat, and there we remained, spell-bound.

Within half an hour all before us was a tossing, blinding tempest of flame! It went surging up adjacent ridges—surmounted them and disappeared in the canons beyond—burst into view upon higher and farther ridges, presently—shed a grander illumination abroad, and dove again —flamed out again, directly, higher and still higher up the mountain-side—threw out skirmishing parties of fire here and there, and sent them trailing their crimson spirals away among remote ramparts and ribs and gorges, till as far as the eye could reach the lofty mountain-fronts were webbed as it were with a tangled network of red lava streams. Away across the water the crags and domes were lit with a ruddy glare, and the firmament above was a reflected hell!

Within half an hour all before us was a tossing, blinding tempest of flame! It went surging up adjacent ridges—surmounted them and disappeared in the canons beyond—burst into view upon higher and farther ridges, presently—shed a grander illumination abroad, and dove again —flamed out again, directly, higher and still higher up the mountain-side—threw out skirmishing parties of fire here and there, and sent them trailing their crimson spirals away among remote ramparts and ribs and gorges, till as far as the eye could reach the lofty mountain-fronts were webbed as it were with a tangled network of red lava streams. Away across the water the crags and domes were lit with a ruddy glare, and the firmament above was a reflected hell!

Every feature of the spectacle was repeated in the glowing mirror of the lake! Both pictures were sublime, both were beautiful; but that in the lake had a bewildering richness about it that enchanted the eye and held it with the stronger fascination.

We sat absorbed and motionless through four long hours. We never thought of supper, and never felt fatigue. But at eleven o’clock the conflagration had traveled beyond our range of vision, and then darkness stole down upon the landscape again.

Hunger asserted itself now, but there was nothing to eat. The provisions were all cooked, no doubt, but we did not go to see. We were homeless wanderers again, without any property. Our fence was gone, our house burned down; no insurance. Our pine forest was well scorched, the dead trees all burned up, and our broad acres of manzanita swept away. Our blankets were on our usual sand-bed, however, and so we lay down and went to sleep. The next morning we started back to the old camp, but while out a long way from shore, so great a storm came up that we dared not try to land. So I baled out the seas we shipped, and Johnny pulled heavily through the billows till we had reached a point three or four miles beyond the camp.

The storm was increasing, and it became evident that it was better to take the hazard of beaching the boat than go down in hundred fathoms of water; so we ran in, with tall white-caps following, and I sat down in the stern-sheets and pointed her head-on to the shore. The instant the bow struck, a wave came over the stern that washed crew and cargo ashore, and saved a deal of trouble. We shivered in the lee of a boulder all the rest of the day, and froze all the night through. In the morning the tempest had gone down, and we paddled down to the camp without any unnecessary delay. We were so starved that we ate up the rest of the Brigade’s provisions, and then set out to Carson to tell them about it and ask their forgiveness. It was accorded, upon payment of damages.

We made many trips to the lake after that, and had many a hair-breadth escape and blood-curdling adventure which will never be recorded in any history.

– – – – – – – _/ _/ _/ _/ – – – – – – –

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, the young man who became Mark Twain, camped on the Nevada side of Lake Tahoe in 1861. First with John Kinney of Cincinnati for four days, then a quick trip the next week with Tom Nye, a veteran of the Gold Country in California. Their camp was at a small sandy cove less than a mile north of the little lighthouse at Thunderbird Lodge, and a little over a mile south of Sand Point at Nevada’s Sand Harbor State Park.

The details of history are often suggested in autobiographical works, but they are confirmed only through primary documentation. In the case of Sam Clemens’ trip to Lake Tahoe, his tale is first told to the public in his burlesque work Roughing It. There he does not give directions to the campsite he used for the two trips to the lake which are wrapped together in the book as a single visit.

Writing some ten years after those two visits, he suggests he was at Tahoe for a month or more, instead of the six to ten days his known calendar for 1861 would allow. At the time of writing, however, he had visited the lake, or passed along it in a Stagecoach, often driven by the colorful Hank Monk, a number of times.

So to determine the location, the historical researcher turns first to the two letters he wrote home at the time of the visit, September, 1861. Only the latter portion of the first letter remains. The opening material probably carried information on the first trip there, and the camp. In the latter portion, he tells us a bit about the camp, and about its location relative to a camp established by his friends and roommates in Carson City. The second letter carries some additional descriptive material about the camp.

From Roughing It the historian needs only three broad facts, items easily remembered by Twain over the ensuing decade. First, Sam Clemens was inspired to go to the lake by his friends in the boarding house, whom he called The Irish Brigade. The name was in honor of their landlady, Margret O’Brien. Second and third, the Brigade authorized him to use their boat and their cache of food, left at the timber claim they had staked at the lake earlier that summer.

Then, turning to documents dating to the time of his visit, the historical researcher will find additional key information. First is a letter written by William H. Wagner, an experienced road engineer, in which he reports progress to Gov. James W. Nye. The letter and court documents are held in the State Archives. Wagner includes a map of a proposed new road up King’s Canyon west of Carson City — up the old Johnson Trail — to Glenbrook and then south to the State Line. He also reports on the improvements being made to firm up their timber claim, mentioning three streams passing across the claim. Court documents filed at that time confirm the membership of the tree claim group, and grant a toll road franchise for the proposed King’s Canyon road. A plat of survey of the claim, surveyed by the County Surveyor and recorded in the Carson City Clerk’s Office in 1862, shows the shape of the claim. It contains the three streams mentioned in Wagner’s letter, written a few days before Sam’s visit to the lake.

An 1865 plat of a township (36-square-mile) survey by Butler Ives, a (U.S.) Government Land Office (GLO) surveyor, pinpoints the location of the Nye log cabin, also present on the county surveyor’s plat and mentioned in Wagner’s letter. Also present are the three streams — today named Marlette, Secret, and Bliss creeks.

Using these documents, Sam and friend came up the King’s Canyon road, which began less than a block from their boarding house; found the Brigade boat at Glenbrook Bay, rowed up to the Brigade cache in Secret Harbor, then rowed up–Sam was 25; John was 20 — so John rowed, of course — to the northwestern corner of the Brigade land claim. It was easy to locate. There is a small sandy cove a few yards north of the point at which the shoreline turns north. Surveyor Ives would note in 1865 that the place where the shoreline turns abruptly north offers a good boat landing, it was within the Brigade land claim. The next dimple in the shoreline, maybe a third of a mile north, was the northern boundary corner. Why go farther north when they could start at the Brigade claim boundary and lay their own claim north. Logs could be floated south to Glenbrook Bay, where Capt. A.W. Pray was establishing a sawmill.

But the careful historical researcher needs more confirmation. On return from the first trip, in late September, 1861, Sam Clemens offers that confirmation in two ways. First, he writes, “On the second day we started to go by land to the lower camp, a distance of three miles…” They were about three miles north (up) from the Brigade camp. The cove is two miles as the crow flies, but it is “the steepest, rockiest and most dangerous piece of country in the world,” in Sam’s words. Then, in the same letter, he writes “After supper we got out our pipes — built a rousing camp fire in the open air — established a faro bank (an institution in this country,) on our huge flat granite dining table, and bet white beans till one o’clock, when John went to bed.”

A search of the shoreline from Secret Harbor to Sand Harbor, most of which is strewn with

huge granite boulders, reveals only one that makes a “huge flat granite dining table.”

And that rock is located right at the northwestern corner of the Brigade timber claim.

The Nevada Board on Geographic Names has recommended to the U.S. Board on Domestic Geographic Names that it should approve naming the little cove just north of Thunderbird Lodge “Sam Clemens Cove,” in honor of the visit made there some century-and-a-half ago by the young man who would within 18 months become Mark Twain. The name can now be used on maps. With confirmation by the board in Washington, D.C., it will be approved for all maps published by the United States Government.

– – – – – – – _/ _/ _/ _/ – – – – – – –

by Larry Schmidt

While working on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1970’s, I was aware that Mark Twain had spent time at Lake Tahoe. I was doing watershed analysis in the drainages feeding Glenbrook Bay. I was curious about Twain’s location at Lake Tahoe and asked several folks where Twain had spent his time and where the camp was located. I received only vague answers.

Almost 40 years later papers by Robert Stewart and David Antonucci in the “Nevada Historical Society Quarterly” provoked a reassessment of “Roughing It.” This along with letters Sam Clemens had written home provided essential facts. In addition, Stewart provided strong evidence for the location of the brigade timber claim. The surveyed plat of the Nye (Brigade) timber claim exactly matches the shoreline and drainage pattern in an area extending from about 3 miles north of Glenbrook Bay to a point near Thunderbird Lodge.

Antonucci critiqued Stewart’s paper for lacking the two summits on the route described by Twain and having too great a distance between Carson City and Lake Tahoe. At the time I was involved with Trails West, Inc. and the Oregon California Trail Association in attempting to locate and map the historic Johnson Cutoff immigrant trail between Carson City and Placerville. I realized that Twain’s description, of passing over two summits going from Carson City to Lake Bigler following an 11 plus mile trip, fit the historic Johnson Cutoff immigrant route. This cured Antonucci’s critique. I then sought a more precise location for the campsite.

I took Twain at his word that he traveled by a boat 3 miles from a point near the only sawmill on Lake Bigler (Pray sawmill located on Glenbrook Bay) to the Brigade Cache. He and Kinney then traveled an additional 3 miles by boat to the campsite. This placed him in the vicinity of a point just northeast of George Whittell’s Thunderbird Lodge. At this point I attempted to refine and verified the location using topographic maps.

The key clues to the location were provided by Twain in his description of the shoreline with small beaches and slopes rising near perpendicular. More important was the fact that the fire burned over a ridge and disappeared then reappeared on a further higher slope. This topographic feature was satisfied by the low ridge separating Marlette Creek from Lake Tahoe. In addition Clemens described balloon voyages over a boulder field lying about 100 yards offshore. I assumed that the 100 yards was referring to the shoreline near the camp. Using Google Earth, a prominent boulder field was evident about 100 yards west of a small bay adjacent to the ridge between Lake Tahoe and Marlette Creek.

At this point I was satisfied that I had located the probable location of Sam Clemens campsite. I decided to go look at that site on the ground. I hiked down along the old access road to the Thunderbird Lodge and then hiked over to look at the small bay. I was looking for any additional features that might confirm the location such as fire scars, boulders positioned to provide shelter and anything else that might provide added evidence. I was aware from Clemens letters home that he had used a large flat granite boulder as a dining and Faro table.

As I hiked around the slope above the small bay, I came to a point on the eastern side. In looking back to the west I caught the afternoon sun glinting off a large flat granite boulder. The hair on the back of my neck stood on end. It was a eureka moment for I had found a large flat granite boulder 5 feet in diameter and about 2 feet high sitting on the shore of the small bay. This, along with the preponderance of other evidence, seemed to provide conclusive evidence that this was the site of Mark Twain’s camp.

– – – – – – – _/ _/ _/ _/ – – – – – – –

by McAvoy Layne

The air was blue from the fireworks in the room that Jack Dreyfus built at Thunderbird Lodge on Tuesday last and it wasn’t about Reid and Angle, it was all about Stewart and Antonucci. The Nevada State Board on Geographic Names was meeting there to hear arguments for and against naming a sandy beach a half mile north of Thunderbird, “Sam Clemens Cove.”

Arguing against the proposal was the admired historian from Homewood, David Antonucci. David contends that Clemens and Kinney took a more northerly route from Carson to Tahoe, and never in fact camped at that particular cove. “Any place you name after him, people are going to automatically assume he was there. The wrong place is worse than no place, because it misleads.”

Persuasive evidence for the Johnson-cutoff route into Glenbrook, leading to the campsite in question was presented by respected Twain scholar Bob Stewart, and supported by retired Forest Service hydrologist Larry Schmidt.

Guy Rocha was in the audience and I was personally concerned about which side he would take, he being Nevada’s preeminent forensic history detective. I have been told that when I walk into a room in the white suit with my “never let the truth stand in the way of a good story” attitude, well, Guy begins to “lick his chops.”

Toward the end of this three hour exchange I was invited to put my shovel in as Mark Twain. I don’t get nervous speaking as Mark Twain anymore, but this time I was sweating like Julia Bulette in church — I wanted that cove so much for Sam.

“Madam Chair, I brought two things with me to this meeting, champagne and strychnine. I commend you all for the impressive body of work you have presented. I brought no charts or maps, but can make my claim in sixty seconds by the watch. Kit Carson first laid eyes on this fairest picture the whole earth affords back in 1844. I will give him the pass, but he also has the range, the sink, and valley, the river, Carson City — and he never set foot in any of those places. I rest my case.”

Well, for once Guy Rocha was on my side, though I did receive an e-mail from His Excellency Rex Veritas on the following morn, chiding me that Kit Carson did in fact see the Carson River, so I will never say that again. (My fingers are crossed behind my back.)

Unless the National Board on Geographic Names overturns Nevada’s decision, which was unanimous, Lake Tahoe can welcome Sam Clemens Cove to the East Shore. David intends to attend that meeting in Washington, and if he does, I might just have to go along with him.

I asked David in private if he wouldn’t consider naming a beach in California, “Mark Twain Cove”. After all, we know Sam hiked to Tahoe on at least three different occasions, and might well have taken two different routes.

One thing we know for certain, Sam Clemens would love the controversy.

– – – – – – – _/ _/ _/ _/ – – – – – – –

by David W. Toll

During meetings in 2014-15, the Nevada State Board on Geographic Names, on its own initiative, held several public discussions relative to naming a site on the northeast shoreline of Lake Tahoe as “Sam Clemens’ Cove.” No formal application had been prepared or submitted.

At the May, 2015 meeting, Darrel Cruz of the Washoe Tribe’s Cultural Committee spoke, respectfully requesting that nothing be named for Samuel Clemens or Clemens’ pen name Mark Twain, in the tribal homeland. The homeland which includes the Lake Tahoe basin and the hills around the lake. In several of his writings, Twain indicated a disdain for members of his and other tribes. He indicated the Tribe would prefer to restore Washoe tribal names for sites in the Tahoe region.

He was also concerned that Twain had expressed racist views when it came to native Americans. In their opinion, that makes it inappropriate to honor him on Washoe homeland sites with a Clemens/Twain name. A member of the public, presenting a map that showed there was no beach at the campsite after the Truckee Dam raised the lake level in the 1900s. He also said that since Twain was a racist, nothing in the basin should be named for Clemens or Twain. In consideration of the concerns expressed by the tribe, the Nevada State Board on Geographic Names voted to table the proposal and took no further action.

The location of Sam Clemens 1861 campsite a quarter mile north of Thunderbird Lodge at Lake Tahoe, was located through well-researched work with 1860’s documents. It is easily identified today by a five-foot diameter flat round boulder at the natural shoreline which Clemens mentions in an 1861 letter.

The tabling of discussion about requesting a formal name for the site does not alter that fact the location was Sam Clemens’ campsite in September, 1861.

As per usual, David, you are right as rain…